Finding Troy, How a City Lost for 3,000 Years Was Rediscovered

Stay ahead of your peers in technology and engineering - The Blueprint

There is practically no one who graduates from school without having learned about the Trojan War, the Trojan Horse, or without having read Homer's Iliad, which was written around 760 BCE. However, the location of the city of Troy and the famous battle that took place there was lost to history for millennia.

The Trojan War

The Trojan War began around 1250 BCE, and on one side was a coalition of Greek states under the leadership of King Agamemnon of Mycenae. On the other side was a coalition of states in the Dardanelles under the leadership of King Priam of Troy. The thing that set the whole thing off was when King Agamemnon's brother Menelaus's wife, Helen, ran off with Paris, a prince of Troy.

See Also

To get Helen back and to punish Troy, the Greeks sent a vast fleet, and they set up an encampment outside of Troy's walls. For ten long years, the battle raged, with the heroes Achilles and Ajax dying on the Achaean side, and Hector and Paris dying on the Trojan Side. Or, if you're a fan of Wolfgang Petersen's 2004 film Troy, it's Brad Pitt and Eric Bana who died, a sad thought indeed.

Achilles bandaging Patroclus Source: Bibi Saint-PolWikimedia Commons

One day, the Achaeans came up with a clever ruse. The emblem of Troy was the horse, so the Achaeans built an enormous wooden horse and left it out on the Trojan Plain. Then, they pretended to sail away.

Believing that the horse was a victory trophy, the Trojans pulled it inside their city walls, which had already withstood ten years of onslaught. What the Trojans didn't know was that secreted inside the horse was a squad of select Achaean warriors, including Odysseus.

Under the cover of darkness, the Greek soldiers dropped from the horse and opened the city gates to the Achaean soldiers who had sailed back during the night. Troy was burned, and many of its people slaughtered, including King Priam's youngest daughter, Polyxena who was sacrificed by the Achaeans.

Enter Heinrich Schliemann

When Heinrich Schliemann was a young boy growing up in the German state of Mecklenburg, his father told him the story of Homer's Iliad, about Achilles and Hector, Paris and Helen, Odysseus and Agamemnon.

Heinrich Schliemann Source: Prometheus/Wikimedia Commons

The Trojan War had also been written about in Homer's The Odyssey, Aeschylus's Oresteia, and Virgil's Aeneid. Schliemann's father told his son that no one knew where ancient Troy had once stood.

Schliemann left school at the age of fourteen, and spent five years working in a grocery store. Then, one day, a drunken man wandered into the store reciting the Iliad and Schliemann's fascination was ignited once again.

Following a stint as a cabin boy at sea, Schliemann moved to Amsterdam, where he began to study languages. Over two years, Schliemann learned English, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian, and he began to learn Russian.

Mastering all these languages allowed Schliemann to prosper as an import-export merchant, and he soon added Swedish and Polish to his list of languages. In early 1851, Schliemann traveled to California and started a bank in Sacramento that was sold for over $1 million dollars worth of gold dust within just six months.

While he was there, in September 1850, California became the 31st U.S. state, and Schliemann automatically received U.S. citizenship. After returning to Russia, Schliemann made another fortune during the Crimean War as a military contractor when he cornered the market in saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sulfur, and lead.

The Greek "treasure"

In 1868, when he was 46-years-old, Schliemann was able to retire from business and to pursue his fascination with finding Troy. He set out for Greece, and there he found his true Greek "treasure", a young woman named Sophia Engastromenos. Not only was she the embodiment of Helen of Troy, she also shared Schliemann's obsession with finding the city.

At that time, scholars believed that Troy lay under a mound at a village called Pınarbaşı. Schliemann concluded that Pınarbaşı couldn't be Troy because it was too far from the sea, and the mound was too large for Achilles to have chased Hector around it three times, as described in the Iliad.

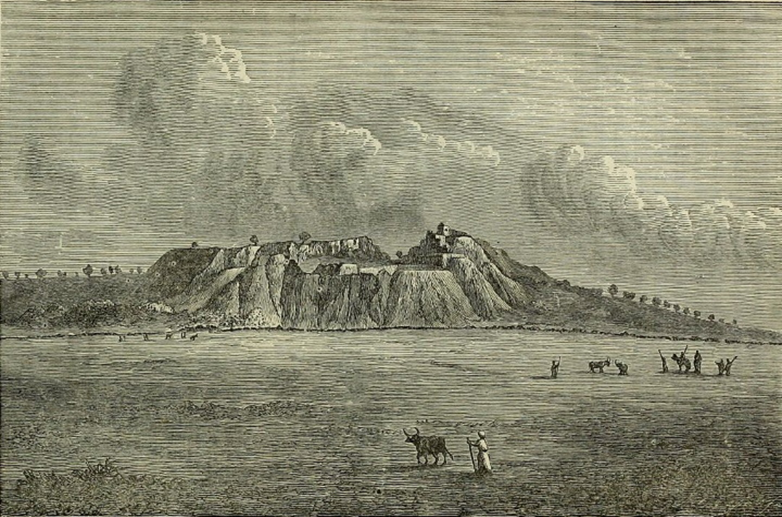

The mound at Hisarlik Source: Internet Archive/Wikimedia Commons

Then, Schliemann met Frank Calvert, a member of an English expat family who were convinced that Troy lay under a mound located at the modern city of Hisarlik. So sure were the Calverts that they purchased 2,000 acres (8 km2) of the mound, however, they didn't have enough money to properly excavate the site, and money was one thing that Schliemann definitely had.

Location of ancient Troy Source: Marcia Wendorf

In April 1870, Schliemann and 100 workers started digging the mound at Hisarlik, and very quickly they unearthed copper shields, a cauldron, axe heads, daggers, silver vases and goblets, and terracotta objects. Eventually, Schliemann unearthed not one, but nine separate cities that had been built, one on top of the other, on the same site. The question was, which of one of them was the Troy of the Iliad.

Schliemann determined that the bottom-most city was clearly Bronze Age, and the uppermost city was clearly Roman. It was in the second and third levels from the bottom that Schliemann found traces of a great fire, the remains of massive walls, and the ruins of a gigantic gate that he concluded had once been the Scaean Gate, the main gate of Troy.

Walls of Troy VI Source: Radomil/Wikimedia Commons

After three years of digging, and moving over 325,000 cubic yards (250,000 cubic meter) of dirt, the finds started slowing and Schliemann set June 15, 1873 as the last day of the dig. The day before the deadline, something in the ground caught Schliemann's eye and he claimed to have grabbed his wife's shawl and jumped into a trench. There, was a hoard of golden objects including diadems, brooches, chains, plates, buttons, bracelets, and golden threads.

Schliemann festooned his bride with golden earrings, necklaces, and bracelets which was captured in the famous photograph below. In a practice that was all too common at the time, Schliemann spirited the hoard out of Turkey and into Greece and although he traded a small portion of the hoard back to Turkey for permission to continue excavating at Hisarlik, the majority of the hoard ended up at the Royal Museums of Berlin.

Sophia wearing "Priam's Treasure" Source: Wikimedia Commons

When the Soviet Red Army captured Berlin at the end of WWII, "Priam's Treasure" was was flown to Moscow, where it seemingly disappeared. It was only in 1994 that the Pushkin Museum admitted that it had the Trojan gold.

Years later, it was determined that the ancient city of Troy actually lay within the sixth layer from the bottom, and not the second and third. That meant that the golden treasure was not that of Priam, but had belonged to a king who predated Priam by a thousand years.

Schliemann's second and third acts

Anyone who thought that Schliemann would now rest on his laurels didn't know the man. He next set his sights on unearthing the graves of King Agamemnon and his friends in Mycenae. It turns out that while Agamemnon had been laying siege to Troy, a man named Aegisthus had been laying siege to Agamemnon's wife, Clytemnestra.

Upon Agamemnon's return to Mycenae, Aegisthus invited him and his closest friends to a banquet where they were all killed. It took eight years for this crime to be avenged by Agamemnon and Clytemnestra's son Orestes, a deed which was made immortal in Aeschylus' Agamemnon, Sophocles' Electra, and Euripides' Orestes.

Beginning to dig in Mycenae in August 1876, by December of that year, 15 skeletons had been discovered lying in multiple graves. Best of all, the bodies were covered in gold and jewels, including diadems, 700 golden laurel leaves, and golden ornaments in the shape of animals, flowers, butterflies, lions, warriors, griffons, deer, and doves.

"Mask of Agamemnon" Source: DieBuche/Wikimedia Commons

The bodies were also covered with golden masks, including one that Schliemann called the "Mask of Agamemnon," and golden breastplates that were said to protect the wearer in death. Only later was it determined that these were not the bodies of Agamemnon and his friends, but those of royalty who had lived 300 years earlier.

Schliemann went on to excavate at Tiryns, and he returned to Troy several more times. Schliemann died in Naples, Italy on Christmas Day 1890, and he is buried in Athens.

The legacy of Troy

In 1996, the Turkish government created a 53 square mile (136 k2) Historical National Park at Hislarlik, and in 1998, the park became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Today, a "Trojan horse" refers to a trick or stratagem where a foe is invited into a protected place. Malicious computer programs that trick users into willingly running them are also called a "Trojan horse", or a "Trojan".

Besides the 2004 movie, Schliemann and Sophia were the subjects of author Irving Stone's 1975 novel, The Greek Treasure.

Source : websites