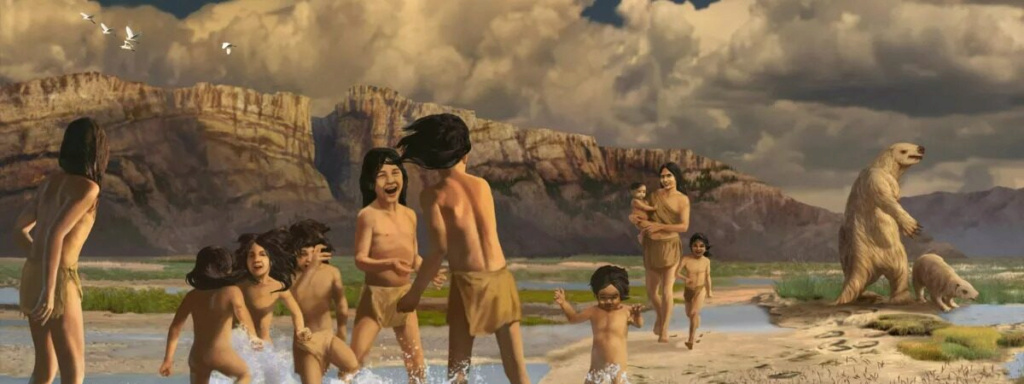

Footprints reveal that Ice Age children were having fun in (giant sloth ponds) 11,000 years ago

More than 11,000 years ago, young children traveling with their families through what is now White Sands National Park in New Mexico discovered things related to their childhood dreams: muddy puddles made from the footprints of a giant, earthly sloth.

There were few things more fond of the little ones than a muddy puddle—there were about four children of them—who raced and scattered through the soggy road of sloths with their footprints imprinted in the woes—the dry lake bed.

New research has found that these footprints preserved over thousands of years prove the existence of a prehistoric tomb.

The discovery indicated that children lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch (about 2.6 to 11,700 million years ago).

“All kids love to play in the muddy puddles, which it used to be,” says Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the UK who studies sloths.

Incredible fossilized footprints indicated that early humans hunted giant sloths.

Bennett has traveled to the White Sands more than a dozen times in the past five years, locating and analyzing footprints left by Ice Age humans and megafauna (animals over 99 pounds or 45 kilograms).

He and his university have made a remarkable number of discoveries, including human footprints dating between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, the oldest definitive evidence of people in the Americas. The discovery of footprints imprinted on the mud of children and sloths was published and reviewed by experts in the newspaper, but Bennett plans to write about them in the coming months, becoming an illustrative map, to help scientists studying similar tracks determine how many people were found there, and how old they were when They made those tracks.

For example, the tracks that Bennett analyzed are not an accurate representation of children's feet, as spongy mud distorted each footprint, but Bennett was able to compare the preserved and stained footprints with recent growth data to infer the children's ages.

Bennett said he found that they had more than 30 footprints crisscrossing the sloth's path, and they were of children ages 5 to 8.

The now-extinct giant ground sloth, probably Nothrotheriops, left its tracks after walking through the area on all fours. Every edition of Sloth is actually a double edition, Bennett said. "When she puts her front paws down, the back paw comes in and tramples on her," he explained. That combination of front and back paw gives the prints a kidney shape.

Each giant sloth's footprints are about 16 inches (40 centimeters) long, Bennett said, and the monster could have been anywhere from the size of a cow to the size of a bear. The footprints are shallow, about 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) deep, but it seems that they were deep enough to fill with water and this piqued the children's interest.

"We see kids' tracks very frequently in White Sands, probably because these kids, like kids today, are racing and leaving hundreds of footprints a day," Bennett said.

He further added that those children and adults in the group were roughly the same foragers who stuck together during the hunt. He also stated: “In the past, you would have taken your son to work. And if it was work across the bottom of the former lake to track down an animal, you would have taken your child with you.”

Bennett added: “It is difficult to date the footprints without a detailed stratigraphy - or the study of rock layers - of the site and without finding any organic material that can be dated using radiocarbon. But based on the discovery of 23,000-year-old prints and the fact that ground sloths became extinct about 11,000 years ago, it's possible that these once-sprayed prints were made between 23,000 and 11,000 years ago.

https://mscience.co/27403/?fbclid=IwAR2F4PWRwCu98Udbo3TDkyzXw_M57bZQDQ44Sfsb-M12rIgkt6Q_evH8k4Y