What we know about Hippocampus, Neptune's new moon

This small world, named after the mythical sea creature, has a surprisingly brutal past.

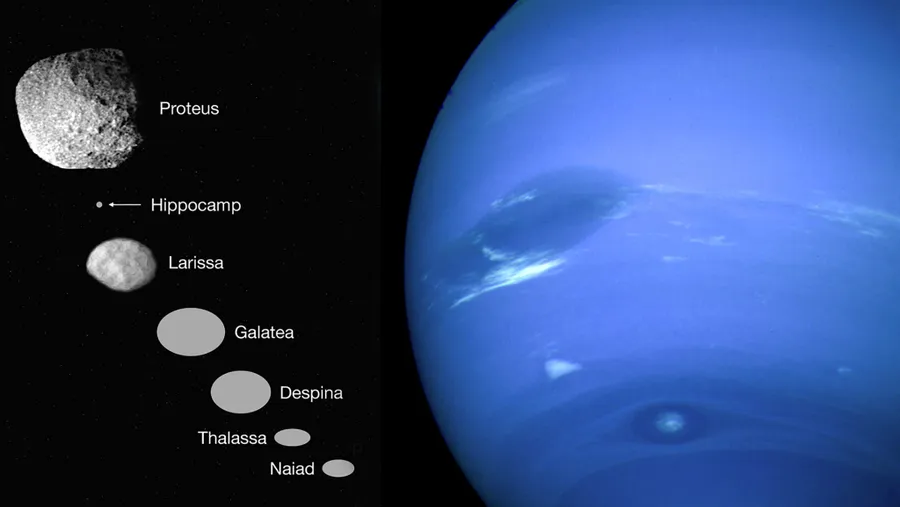

In 1989, Voyager 2 flew by Neptune, on the right, and spotted six small inner moons, shown in the composite on the left. A tiny moon between Proteus and Larissa had not been detected at the time; Mark Showalter discovered the moon in 2013 using the Hubble Space Telescope and officially named it Seahorse. (This image is not to scale)

photograph by left: illustration by mark r. showalter , seti institute; right: nasa , jpl

For billions of years, a small moon orbiting the ice giant Neptune hid among the stars. The tiny world now has a name, and scientists are beginning to piece together its violent history.

"It was incredibly hard to detect," says Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute, who first spotted the moon in 2013 and describes it today in the journal Nature . The recently described satellite brings the number of known celestial companions of Neptune to 14. An avid diver, Mark Showalter chose to name the small moon Hippocampus, in reference to the fantastic creature described in Greek mythology whose anterior part was that of a horse and the posterior that of a fish, a snake, or a sea monster. This mythological figure then gave his name to the small seahorses that Mark Showalter particularly appreciates.

"When it came time to choose a name from among Greek and Roman maritime mythology figures [en relation avec Neptune, roman god of the sea, ndrl ], I told myself that I would not look very far", says- he.

The most difficult thing was first to discover the small moon. Nestled relatively close to Neptune and about 21 km wide, this rocky object is small enough to fit into the narrowest part of the English Channel. It took several years of painstaking research to detect its presence in images from the Hubble Space Telescope .

“You can only find out about these moons because people like Mark Showalter figured out how to distinguish every photon in these images,” said Heidi Hammel of the American Universities Research Association.

ACCIDENTAL MOONLIGHT

Not necessarily wanting to go moon hunting, Mark Showalter stumbled upon this little world after developing a new way to search for faint structures around Neptune. He and his colleagues had pointed Hubble at Neptune in 2004, 2005 and 2009 in hopes of getting a good look at the bizarre ring fragments surrounding the big blue planet. Because these arcs are weak, the team overlaid long-exposure Hubble images, which boosted the telescope's sensitivity.

It was only later that Showalter decided to apply this technique to search for moons.

One by one, he sighted the known inner moons of Neptune, Proteus, Thalassa, Galatea, Despina, Larissa and Naiad, a moon that had not been observed since the Voyager 2 probe's flyby in 1989. Yet among these distant worlds, an intruder - a faint point of light behaving like a moon, which had never been sighted before.

After tracking the movements of the observed point, Showalter and his colleagues were convinced that they had stumbled upon a moon, given its brightness and data from another observation campaign conducted in 2016. They then estimated its size .

"Really, that's a point," says Showalter.

A HISTORY OF COMETARY VIOLENCE

More disturbingly, the orbit of Hippocampus merges with that of Proteus, the largest of Neptune's inner moons. The two moons are so close to each other - about 7,500 km separates them - that it's unlikely that Hippocampus got there by chance.

Showalter hypothesizes that it formed after a comet struck Proteus and orbited debris around Neptune. This debris would have grouped together to form a new moon. Since then, comets may have hit Hippocampus on several occasions.

"It's in a region around Neptune where you're far enough that when you break something, it ends up reforming into the moon," Showalter says, adding that "a lot of the inner moons of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune have probably broken several times during their history.

But telling the detailed stories of Hippocampus and other easily observable objects on the fringes of the solar system requires a much sharper instrument than Hubble or a spacecraft sent to the cosmic depths.

“You can find them with Hubble,” says Hammel. "But you can't attempt to understand the detailed geology, the detailed chemistry of the objects that are on the outskirts of the solar system. »

Source : websites