Io, the most volcanic moon in the solar system

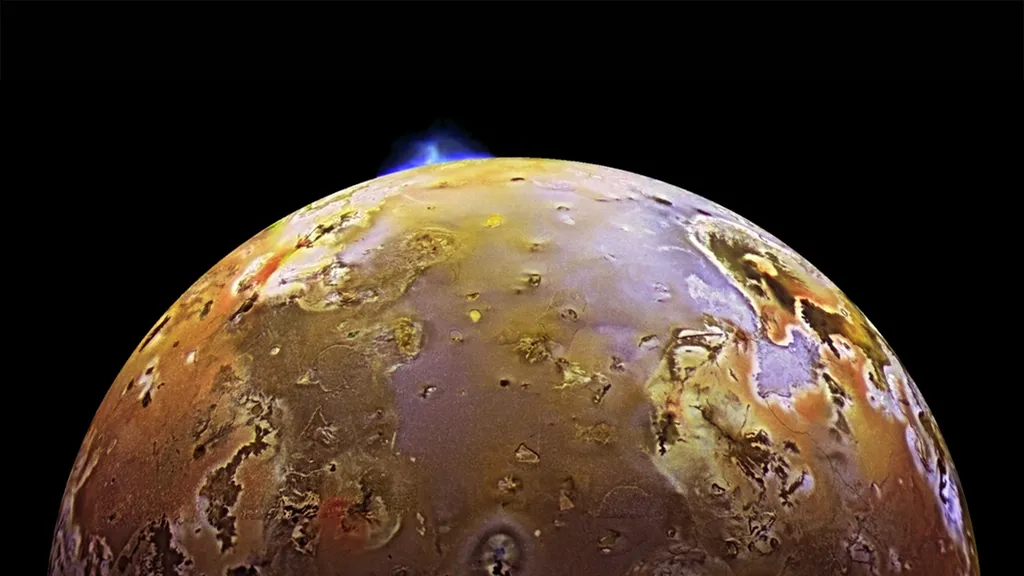

In this photo taken by the Galileo probe, we can clearly see a volcanic plume rising from the surface of Io, Jupiter's third largest moon and the most geologically active body in our solar system.

A massive new report from Jupiter's moon Io suggests that this explosive world is even stranger than previously thought.

About forty years ago, the Voyager 1 probe crossed the path of one of Jupiter's largest moons and shed light on an incredible phenomenon: this rocky moon called Io was in fact a champion of volcanism and presented on the surface the first volcanoes in eruption that Man had the opportunity to admire outside the Earth. Of the hundreds of volcanoes on Io, many are far larger in size than our largest cities. Their powerful eruptions sometimes give rise to volcanic plumes of supernatural proportions, sometimes reaching 480 km in height.

Now scientists are lifting the lid on more than five years of images taken from the top of a Hawaiian volcano that have helped them recreate the most detailed atlas of this mysterious moon. Their work, published in The Astronomical Journal, shows how far they've come since the grainy photos of Io's volcanic plumes taken by Voyager.

The research they conducted also confirms that Io is a strange star, much stranger and more difficult to explain than anyone had dared to imagine. The volcanoes seem to be in the wrong place, the most radiant eruptions appear to be confined to a single hemisphere, and Loki Patera, a lava-filled crater with an area of more than 20,000 km², flatly refuses to bend the rules.

Sure, the new data is riddled with puzzles, but it's nonetheless a "gift to the planetary science community," notes Ashley Davies , study co-author and volcanologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. . After all, these abundant and geochemically primitive eruptions are similar to those that once hit the surface of our planet; looking at Io today is therefore a way of understanding the massive eruptions that have occurred here over the past 500 million years.

"It's a window into Earth's past," Davies concludes.

A SYNCHRONIZED BALLET

Unlike Earth's eruptive summits and trenches, volcanic activity on Io is not fueled by possible hot spots trapped during its formation, nor by the decay of naturally radioactive compounds contained in its rocks. She is made the fruit of his orbital manipulations.

Io is one of the four Galilean satellites of Jupiter alongside Ganymede, Europa and Callisto. These large moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610 are all visible from Earth with a small telescope. It turns out that with each revolution of Ganymede around Jupiter, Io orbits four times and with each revolution of Europa, Io orbits twice. This phenomenon called orbital resonance and more particularly Laplace resonance in the proportions of the Galilean moons of Jupiter forces Io to adopt a more elliptical orbit than it would otherwise and the gravitational tugs caused between the satellites cause the ebb and flow of the surface solid of Io, with differences of up to 100 m.

Combined with the gravitational pull exerted by Jupiter, this orbital ballet generates significant heat within Io through friction and consequently produces an incredible volume of magma , which a paper published in 1979 predicted before anyone had even been able to lay eyes on the volcanic plumes rising from the surface of the satellite.

how many moons do the planets in the solar system have?combien ?de lunes possèdent les planètes du système solaire

Due to its bizarre volcanism, Io is plagued by fearsome extremes. Its unstable and short-lived atmosphere is not thick enough to retain heat, so the average surface temperature is -130°C. Conversely, some of its lava flows can reach 1,650°C , unheard of on Earth.

Even though Io is about 4.5 billion years old, its massive production of lava indicates that its surface is no more than a million years old, adds Alfred McEwen , a planetary geologist at the University of 'Arizona. Its volcanoes often take the form of cauldrons carved into the crust known as patera. Sometimes they manage to contain their lava flows but other times they spread and from time to time, these pateras explode by projecting their contents a good distance.

THE JOKER GOD

With so many volcanic mysteries to unravel, the study's lead author and California Institute of Technology planetary scientist, Katherine de Kleer , turned to the Keck and Gemini observatories atop the Mauna Kea volcano on the Big Island. of Hawaii hoping to be able to study in its smallest details the evolution of the behavior of Io. Due to the high demand for access to these telescopes, she sometimes had to reduce her appointments with Io to 20-minute sessions, but after five years, the accumulation of these short interviews enabled her to build a set considerable amount of data.

As usual, the Loki Patera imposed itself on the front of the stage. More powerful and more enduring than any of its competitors on Io, the Loki Patera is responsible for a venerable 10% of the heat given off by the moon. The association of old data with these recent observations seems to show that the volcano activates and dies out every 460 to 480 days , which according to de Kleer corresponds to the repeated variations occurring in the shape of the orbit of Yo.

More data is needed to confirm this trend, and at this time it is unclear whether less powerful Ionian volcanoes follow a similar cycle. According to McEwen, this is a reasonable assumption since the brightness of plumes rising from the south pole of the icy moon Enceladus also fluctuates with its orbit around Saturn.

However, de Kleer prefers to remain cautious given the Loki Patera's annoying tendency to contradict all articles written about his behavior shortly after publication.

Indeed, just over a year ago, a team led by Planetary Science Institute scientist Julie Rathbun used Loki Patera's apparent bright and dark cycle to predict the next eruption. to May 2018, and she had been right. On this momentum, the same researchers then predicted an eruption in September of this year; what was their disappointment when in July the volcanic activity of Loki Patera reached its climax before plunging back into silence a few days later, again defying all predictions.

“We absolutely have to stop naming landforms after prankster gods! jokes Rathbun.

It is believed that the light cycle of Loki Patera could be influenced by the regeneration of the lava lake. As parts of the satellite's lava lake cool, they plunge below the surface and could trigger a series of large, progressive waves visible at the surface. Unfortunately, as Davies points out, it's quite difficult to get satisfactory answers comparing Loki to the lava lakes currently present on Earth because the difference in size is such that simply scaling up Earth's mechanics isn't enough. not.

BURNING QUESTIONS

The data also seems to confirm another Ionian mystery: the brightest flares have a monopoly in the hemisphere permanently turned towards Jupiter. No one can really explain this volcanic bias at the moment, de Kleer calls it “entirely enigmatic at this stage. »

Also, the volcanoes themselves seem not to have settled where all the models claim they should be. Based on the interior regions of the satellite being heated by gravitational forces, the models estimate that volcanoes should concentrate near the poles or the equator. However, observations show that the actual positions of Io's volcanoes do not match any major pattern of warming.

The debates are also animated around the aspect of the infernal sub-surface of the satellite. In the 1990s and early 2000s , the space probe Galileo provided experts with evidence suggesting that a colossal ocean of magma lurked beneath the surface . It is not impossible, however, that this huge ocean is in fact several pockets of magma or even a single spongy layer soaked in fluid .

There are also explosive flares on Io so powerful that just one of them is capable of doubling the brightness of the satellite. In 2013, de Kleer had observed three such eruptions in the space of two weeks and since then, despite the five years spent scrutinizing this moon, nothing. "It's weird," she comments. “Where did they go? »

A NEW VISION

While it may seem like this new study brings more questions than answers, the work sheds light on the various ways in which a deeper understanding of Io could help unravel some mysteries about Earth and other geologically active bodies.

“The story of volcanology is this, you see old deposits without really understanding them,” McEwen explains. "Then we see an eruption and then we're like, Ah-ha , now I get it. Well, similarly, observing eruptions on Io could help us piece together the history of eruptions on our planet. And this, in particular for the Trapps of Siberia whose long and powerful eruptions would have probably caused the most important mass extinction that the Earth has known.

Understanding the effects of Io's heat source could help shed light on the forces at play in the depths of aquatic worlds like Enceladus. There, similar tidal friction forces may have caused, due to the influence of geothermal conditions , the appearance of a liquid ocean under the Saturnian satellite's ice shell. An ocean that could potentially host life.

"Io has truly transformed our vision of the future of exploration and redefined our expectations," concludes Linda Morabito , who was the first to detect volcanic activity on Io while working at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1979. It's no wonder, then, that McEwen and his colleagues are hopeful of one day sending a space probe to circle Io, an event that could be seen as the ultimate recognition of these groundbreaking observations. made from Earth from the lighthouse of our solar system.

Source:websites