Why it's time to probe Uranus

If we want to send a probe to Uranus, we need to start planning and fundraising now to take advantage of the open window in 2032. Indeed, such an opportunity is not going to come around any time soon. In a new article , Dr. Kathleen Mandt, planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, explains the benefits of such a project.

An opportunity to seize

Mars , Venus , Jupiter or even Saturn have all received more or less attention from the scientific community by hosting probes or landers. However, Uranus is with Neptune a little "left behind" of the solar system. Even some asteroids have been highlighted more.

It must be said that these two "forgotten" do not make the task easy. Uranus is more than 2.7 billion km from Earth, while Neptune comes no closer than 4.3 billion km. At such distances, it obviously takes a lot of energy to bring a ship in a reasonable time, which partly explains why they seem neglected by the scientific community. However, these times can be considerably shortened.

The only probe passed close to these two planets (Voyager 2 in the 80s) had benefited from a perfect alignment of the giants of our system which only occurs once every 175 years. These positions allow ships to take advantage of gravitational assistance to orient themselves and accelerate towards their target.

Since that whirlwind passage, no real opportunity has presented itself, but that is about to change. Indeed, even if in 2032, Saturn and Neptune will not be as well placed as fifty years ago, Uranus and Jupiter will align again . And if we want to take advantage of this assistance, we should start now according to Dr. Kathleen Mandt. Otherwise, we will have to wait for decades.

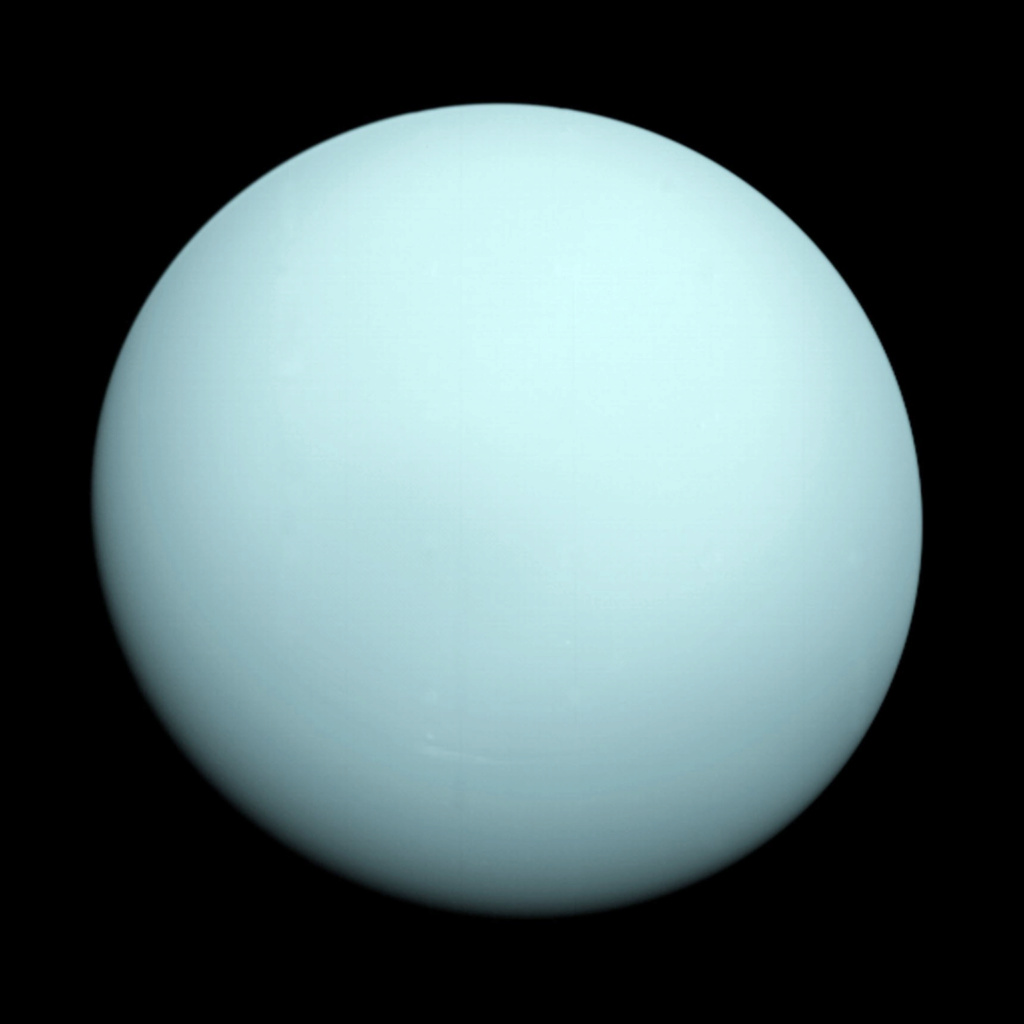

Uranus seen by Voyager 2 in 1986. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Why send a probe?

This is obviously not the first "foot call". Several researchers have been campaigning for the sending of a probe for years. Recently, a new report covering the next ten years of American planetary science and astrobiology also deemed it a “priority” to send an orbiter and probe to Uranus.

And for good reason, there are many reasons to study this “ice giant” more closely. On the one hand, its strange inclination (98 degrees relative to its orbital plane) obscures searches from Earth. This strange position is believed to be the result of a collision with a large object, but we probably won't know until we can study the planet in more detail.

As Dr. Kathleen Mandt points out, visiting Uranus could also help answer one of the biggest unanswered questions about the solar system: where did the giant planets form and what path did they take to end up at their current location? The models predict different formation and migration scenarios. However, all of these ideas require measurements of isotopic ratios and noble gas abundances in each planet's atmosphere to verify which modeled scenario is most accurate. This demonstrates once again the importance of sending a probe on site to collect samples.

Understanding these questions would have vast implications for explaining, among other things, the distribution of small bodies in our solar system and, by extension, the delivery through these bodies of small masses of water and vital elements to the inner solar system.

Finally, a mission could study the magnetosphere of Uranus and provide new information on its internal structure (is the core solid or diffuse?). Another interesting point: Uranus has one of the most beautiful sets of rings in the solar system, but also 27 known satellites of medium and small size, some of which could contain liquid water nestled under their shell of ice.

Source : websites