Neanderthal man: DNA analysis casts doubt on his migration

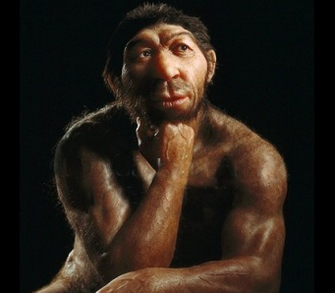

DNA taken from this Neanderthal jawbone discovered in Belgium sheds new light on when this close relative traveled through Europe and Asia.

DNA samples taken from 120,000-year-old bones are surprising and shed new light on the history of this close relative of man.

In 1856, curious bones were unearthed in a limestone quarry in the Neander Valley in Germany. Although the skull and bone fragments vaguely resembled those of modern humans, the forehead was too robust and the bones too heavy. It took eight years for scientists to identify the fossils as the first trace of an entirely different extinct human species, Homo neanderthalensis .

Year after year, discovery after discovery, researchers have completed the portrait of Neanderthal Man by exposing his place of life, his benevolent attitude towards the youngest and perhaps even his art . Today, the analysis of DNA samples taken from two European Neanderthals allows scientists to learn more about the journey of this species through the prehistoric world.

The predecessors of Neanderthals would have separated from the ancestors of modern humans at least 500,000 years ago before dispersing across Europe, Central Asia and Southwest Asia. Published June 26 in Science Advances , the new study suggests that two of these ancient Hominini believed to have lived 120,000 years ago had a genetic makeup eerily similar to that of much more recent Neanderthals. In addition, one of the two Neanderthals studied also had an unusual fragment of DNA suggesting interactions with another group of hominini that remains to be identified.

These discoveries made possible by the progress of DNA analyzes sow doubt on the migratory history of Neanderthal Man and his interactions with our first ancestors, reports Kay Prüfer , author of the study and researcher at the Max-Planck Institute. of evolutionary anthropology in Germany.

“Without this technology, we wouldn't have been able to connect these different pieces of history,” he says.

NEANDERTAL PUZZLE

Previous research suggested that Neanderthals had a rather mixed genetic heritage, resulting from interbreeding across Europe and Asia. However, data indicating this genetic similarity was largely restricted to the era of Neanderthal Man's extinction, around 40,000 years ago.

Other elements also made the team wonder what might have been overlooked in the past. The remains of a Neanderthal Man estimated to be 120,000 years old have, for example, been discovered in the Siberian cave of Denisova, the one that gave its name to the long-toothed cousin of the Neanderthals: Denisova Man . This individual known as the Altai Neanderthal had a very different genome from later European Neanderthals.

Her genetic makeup even differed from the Neanderthal half of the genome of a female hybrid unearthed in this same cave , born to a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father around 90,000 years ago. The mother's genes were closer to those of later Neanderthals. All of this suggests that at some point the Neanderthal population in this region was replaced by another group of the same species. But then, where did these successors come from? Was this mutation limited to the eastern part of their range?

To solve this mystery, the team turned to a 120,000-year-old femur discovered in Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave as well as a similarly aged jawbone from Scladina Cave in Belgium. They then proceeded to extract mitochondrial DNA, a genetic fragment transmitted from mother to child, and nuclear DNA transmitted by both parents and therefore carrying denser information.

Then came the complex stage of genetic analysis. Due to their fragile nature, DNA strands tend to break down over time and samples are easily contaminated.

“We had to get creative to make it work,” says Prüfer, adding that they used a variety of techniques to make sure contamination didn't influence the results.

The results they obtained surprised them: the two European Neanderthals dated to 120,000 years ago were closer to the Neanderthals who roamed Europe tens of thousands of years later than to the Altai Neanderthal discovered in Siberia living at the same time. The two older individuals were otherwise remarkably genetically similar to the female hybrid's mother.

This genetic similarity between the Neanderthals of Europe and the Neanderthal half of the hybrid female shows that these individuals may have been members of the group that replaced the first residents of Denisova Cave. And since both of these specimens are similar in age to the Altai Neanderthal, it's possible the replacement had already started 120,000 years ago, says Adam Siepel , a computational biologist at the Simons Center for Quantitative Biology in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

“These two individuals seem to be related to the origin of this replacement population since they more or less lived at the time of the transition. » he explains by e-mail.

entangled roots

While the analysis has shed light on some chapters of Neanderthal history, some doubts remain. First of all, despite the similarity of the nuclear DNA of Neanderthals across time and space, the mitochondrial DNA of the femur from the Stadel cave differs in every respect from that of the Neanderthals studied so far. there, observes study co-author Stéphane Peyrégne , who conducted this analysis as part of his doctoral research at the Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

This mysterious mitochondrial DNA had already been mentioned in a study published in 2017 in the journal Nature . In the latest study, the team confirmed the accuracy of this analysis and used numerical tests to show that the genetic variation was not just due to chance. However, they are not able to explain how it appeared.

Maybe she comes from another group of ancient Neanderthals who split off from the rest of the population a long time ago. Or perhaps, the researchers propose, that the ancestors of early humans had interfered with the genetic heritage of Neanderthal Man. Although members of this long line of European Neanderthals were long extinct, we know that they interbred with modern humans who left Africa around 55,000 years ago, passing on 2% of Neanderthal DNA in the genome of modern humans of non-African origin. (Read: Denisova's human line could represent three human species. )

It could also be that the reverse scenario happened and that an earlier group of modern humans passed DNA to Neanderthals. In this case, modern humans would have bequeathed at least two types of mitochondria to Neanderthals, explains Prüfer. One would have evolved into the sequence identified in the Stadel cave femur, while the other would have given rise to all the other Neanderthal mitochondrial sequences discovered to date.

This discrepancy in results between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA is surprising but perhaps it shouldn't be, points out Qiaomei Fu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, a specialist in prehistoric DNA, uninvolved. in the study.

"Given that the same scenario is found in the Denisovans, along with other such evidence, I think it's becoming increasingly clear that the interbreeding that has occurred throughout hominid history is quite complex. and that they may well have happened frequently,” Fu explains via email.

Even shrouded in all these mysteries, this latest study brings new details to the story of an ancient relative of Man with whom we are only beginning to get to know but who with each discovery seems more and more familiar to us.

“I think it changes our perception to some extent,” Prüfer concludes, “to understand that there really was a relative who might have looked like us and who…inhabited the same areas that we currently inhabit. »

Source :websites