April 1980 or the foundation of an inclusive historical reconstruction. By Salem DJEBARA*

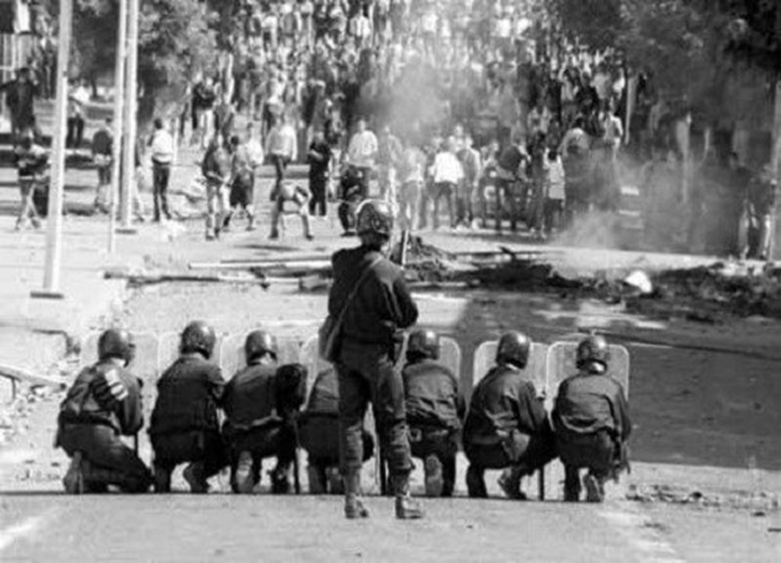

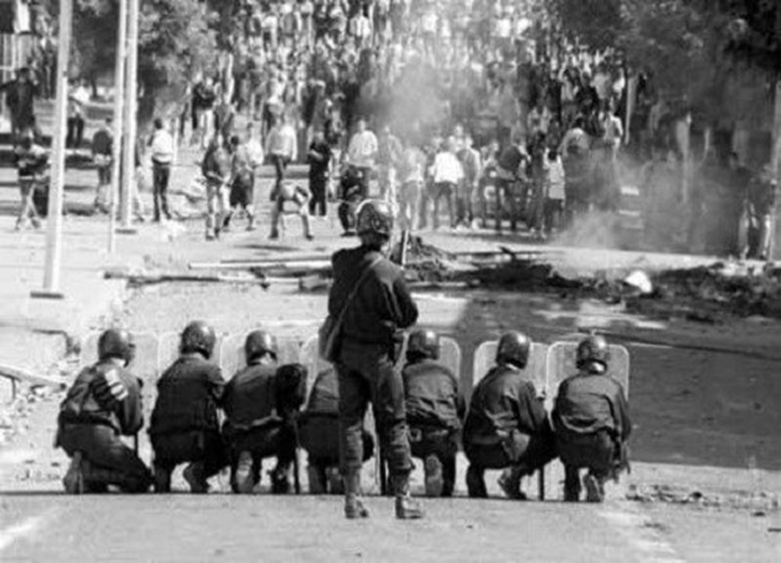

Areal telluric shock in the history of independent Algeria, the Amazigh Spring, by its singularity, shook the foundations of a system that was thought to be irremovable. Deeply convinced that a " culture only dies of its own weakness " to use the words of A. Malraux, Kabyle society will, without recourse to violence, take back the initiative of its destiny by asking the question of what Algerian identity is. How could such an event have taken place when we thought the question had been definitively sent to the five hundred devils?

A virtuous maturation

The culmination of a long process of raising awareness born of the will and determination of young Kabyles to fight against the ostracism displayed against their language, the Amazigh Spring finds its essence in the conjunction of five parameters:

ideological, it is the outcome of a long work of multidisciplinary awareness raising;

conceptually, it has been nourished by the works and reflections of the man who can be considered the spiritual father of berberity: Mouloud Mammeri;

social, it is supported by an entire region;

psychologically, he broke the wall of fear distilled in the social body by an omnipresent political police which reigned “ over the real and the imaginary ” in the words of Nabil Farès;

political, he enacted a major divorce from the central power, a divorce which still persists in the light of the abysmal weakness of the participation in the elections and the climate of tension which characterizes the nature of the region's relationship to the regime

Representative of the entire sociology of the region where the female element was far from being a simple appendage to participation, massive in its public expression and in tune with collective aspirations, the Amazigh Spring of 1980 was the first major manifestation of a form of identity stripped of folkloric and emotional tinsel in favor of a political value. It was neither more nor less than denouncing the denial of identity (all it took was a spark for the region to ignite) and to deconstruct the official discourse holding in suspicion any attempt to think otherwise. But, more than that, at the heart of its problematic as well as its action, the Amazigh Spring has managed to avoid the trap of singularity by seeking common and shared codes (linguistic plurality, individual and collective freedoms, social justice, such were its main watchwords) able to organize the exit of the individual from his ethnic yoke and ideological ruts. In this sense, it is not at all exaggerated to write that the Amazigh Spring was both a compass and a crucible for Algerian democratic struggles.

While supporters of uniqueness continued to blow on the embers, calling the movement " to be at the service of foreign interests " (the famous party of France: Hizb França), the press to orders poured into the amalgamation and rudeness 1 and the local clerks relayed a provocative speech (attack on national unity), nothing could shake the determination of the collective action to achieve its demands in a peaceful framework. At the height of this despicable response to the legitimate aspirations of an entire region, no activist expressed the absurd idea of any linguistic or identity separatism and even less of territorial separatism.

Assume the complexity of struggles

It is incontestably in the field of ideas and perspectives that the spirit of April 1980 will deeply mark consciences by this questioning: how to be of one's time without renouncing one's cultural identity, nor compromising the imperative of a common destiny ? Quite simply, by the regime of freedoms: freedom for the individual to give himself the power of his own autonomy; freedom for the citizen to think freely; cultural and linguistic freedoms for minorities. Such is the problem thought up by Mouloud Mammeri and translated into action in the spring of 1980 and which remains more than topical even today. Through this act, the Berber Spring has been able to find the ways and means to raise a hitherto affective claim to the stage of a civic claim.

The editor-in-chief of the newspaper El Moudjahid, official organ, of March 20, 1980, in an article entitled "the lesson givers" attacked in an ignominious and delirious way the university community and Mouloud Mammeri without quoting him obviously: "At a time when the Political Leadership, listening to the masses, takes charge of all the problems of citizens, in order to resolve them in a comprehensive and fair manner, our people have nothing to do with givers of lessons and particularly people who gave nothing either to their people or to the revolution, at times when the contribution of each Algerian to the national cause was a symbol of sacrifice and love of the fatherland”. Obviously, the right of reply was never published. Let the reader still appreciate Mammeri's response: "a worthy journalist (and there are many, I assure you) considers that intellectual honesty does exist, and that it is one of the fine attributes of the very function and especially when one writes in a national organ, there, less than elsewhere, one cannot allow oneself to fool around with the truth. I speak of the truth of the facts, because for that of the ideas, one needs a solid dose of presumptuousness to claim that one holds it. But obviously such scruple does not suffocate you. With superb assurance and in extreme confusion, you legislate better, you teach lessons”. it takes a solid dose of presumptuousness to pretend to have it. But obviously such scruple does not suffocate you. With superb assurance and in extreme confusion, you legislate better, you teach lessons”. it takes a solid dose of presumptuousness to pretend to have it. But obviously such scruple does not suffocate you. With superb assurance and in extreme confusion, you legislate better, you teach lessons”.

However, the movement will have lacked a momentum of national solidarity and to raise the emotional charge to the rank of political thought to transform the essay. Fault lines will soon appear to plunge the movement into a state of lethargy, just when society needed it most.

Since “the worst is not always certain” Calderon de la Barca tells us and “hope gives rise to reasons to hope outbids” Alain, despite the relative weakness of Amazigh public opinion , aggregated, homogeneous, able to impose its own ideas in the debate, things nevertheless took a positive turn not only in Algeria, but on the scale of North Africa.

The leaden screed into which the Amazighs had been pushed ended up jumping.

For nearly half a century, we have been counting progress. They were unimaginable in the 70s. By force of circumstances, the Amazigh question has become the keystone of a new hope around a line transcending the ghetto of a fixed and essentialized identity in favor of a dynamic approach of a constructed identity. An identity, never sheltered from the accidents of history, nor completely disconnected from the gravity and the illusion of the past.

Also, having grasped the relevance of the metamorphosed identity and its complexity, the Amazigh Spring has been able to avoid the trap of ethnic determinism and open up to the citizen the prospect of defining himself by what he thinks and by the choices he is called upon to act democratically and conscientiously. This is the message of April 1980. A message that is more topical than ever, the spirit of which needs to be revived for a credible and desirable alternative to the rebuilding of North African identity within the framework of a collective project. , freed from the fables of watered-down history and inscribed in the imperatives of the present and the challenges of the future. Is such an ambition desirable and achievable? Desirable, yes, it still is and is verified, every day, in the attachment of the populations to speak their language, and this, despite a process of deculturation of several centuries! . Achievable, it depends on the will of the Amazigh speakers to no longer be “subalterns” in their history. It is therefore up to them:

to impose in the debates the centrality of the Amazigh question in any work of refoundation, while assuming a process of historicization that is not adjectivized. “ Like a compass, you must first prick the point, which is that of your identity, in order then to be able to open up to the other ” to use this image of the Tunisian philosopher S. Mestiri. It is a prerequisite for the affirmation of an inclusive, civic doctrine, freed from the snares of arranged history;

to bring about a process of breaking with the nihilism and sophism of Arab-Islamism. A veritable exclusivist and a-historical ideological construction, built on a truncated reference to history, Arab-Islamism renders unintelligible the possibility of thinking, judging and acting freely. Main victim of this ideology: the Amazigh language which, by leaving official history, has made impossible any historical narrative in its diversity and complexity. Beyond being a communication tool, a language is first and foremost a memory! By dispossessing his being, it is not only the principle of equal rights that he is denied, but also his inability to have a grip on reality that is organized.

?What prospects

The official recognition of the Amazigh idiom in Algeria and Morocco, its tolerance in Libya and its affirmation within the Tunisian intelligentsia are they heralds of a historic reparation? The answer belongs to time. But at this stage, it is permissible to say that this relaxation is indeed proof that the Berber cause has succeeded in making itself heard and in imposing itself in the debate despite attempts at marginalization. The result of a long fight, the cause is now anchored in people's minds in Morocco as in Algeria, in Tunisia as in Libya or Mali. Nevertheless, it would be a regrettable mistake to conclude that it is irreversible or to be satisfied only with breaking with the artifices of Arab-Islamism so that everything works out.

djamel zenati

first, with the phantasmagoria of anteriority which conveys an essentialist discourse in total contradiction with the sociology of North African settlement and its history. However, shaped by a history that is always in motion, the identity of a people cannot be indefinitely the same across time and space, even if we can agree on the invariability of its substance. Historical continuity cannot exist in the absence of consideration of all the legacies that the State, in its modern expression, has the duty (it is its raison d'être) to knead in order to make it a collective project. . In the North African space, different cultures and ethnic groups coexist that all the trials of history condemn to unite in order to preserve the heritage of yesterday and not compromise the hope of tomorrow. No matter who prays or does not pray, no matter who speaks this or that language; what counts today is to lift the veil on history, to recognize oneself in values and to trace a path to hope for the passage from a narrow conception of identity to a humanly thought out conception so that " the country finally comes to meet its children to use an expression borrowed from a French politician. If anteriority, as a historical fact, is a constituent of collective memory, it is still necessary to maintain it and teach it as it is, but from there to establish it as an exclusive right can at any time contravene the principle of equal rights and a common destiny. The principle of precedence and blood would then supplant that of the ground, putting pressure on social cohesion. Which amounts to saying that the public space is not this place of collective deliberation supposed to carry out the common project, but a space of confrontation of memories and historical, religious or linguistic legitimacies. Let's not be cruel all the same towards the supporters of the primacy of anteriority. Often,

then, with victim postures. Like the characters of Heraclitus, the Amazighs, while being “ awake, they sleep ”. Awake in their ability to grasp reality, they sleep when it comes to translating it into political and civic action. Revealing the absence of critical thought, this paradox can only amplify the phenomenon of explanatory deculturation for a good part of the victim postures. It is true, as Jean Daniel (1920-2020) said: “ When we have no control over things, we take revenge on the other ”. Unless this is the revealing index of a cultural life that is not very creative and therefore ultimately of the absence of a historical memory.

These ruptures cannot be conceived in the absence of a modern and democratic culture. It is up to both of them to assume a plural history made up of several memories and to claim the postulate of the philosophy of human rights while nourishing the ambition of a common destiny based on solidarity and otherness.

Utopia? Certainly not ! Tragic historical situations have taught us about the will of societies to rediscover the meaning of history, of ethics, of humanity on the condition of not alienating their autonomy of critical thought and of reclaiming their capacity to conceive a model of values and principles where doubt would take the place of certainties, reason that of religious vulgate, freedom that of totalitarian temptations, solidarity that of vileness... Otherwise, there will remain Baudelairean remorse, "who laughs , wiggles and twists and feeds on us like the worm of the dead ”. We deserve better.

*Retired university teacher, animator of the Amazigh Cultural Movement.

Source : websites