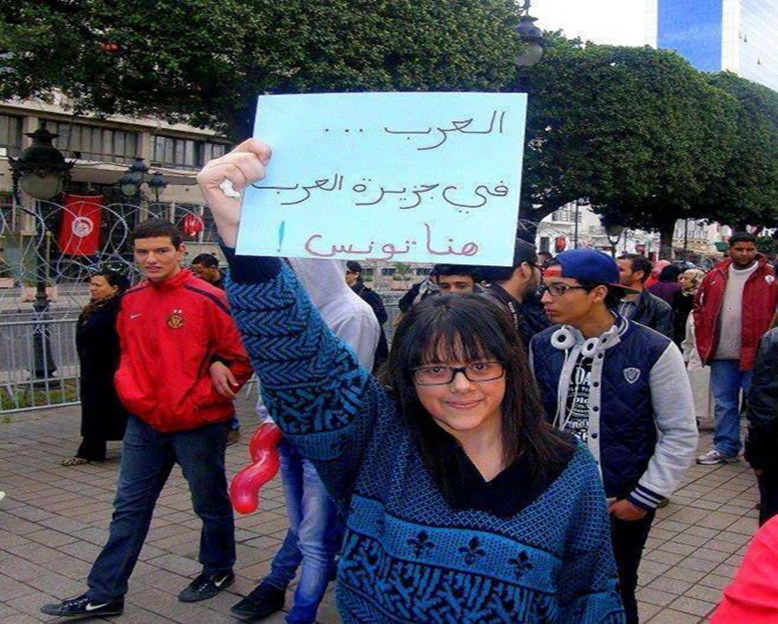

Tunisia. In search of a Tunisian Amazigh spring. By Monia Ben Hamadi*

It is necessary to go to the South of Tunisia, to Tataouine, Matmata, Gabès or even the island of Djerba to hope to hear people, often elderly, still speak one of the local Amazigh languages, the Tunisian Chelha or the “Libyan oriental” – Amazighe language of Zouara -, which make up the Eastern Zénète languages spoken in Tunisia and Libya. The Amazigh speakers of northwestern Tunisia, in Siliana or Kef, are even rarer.

Renewed citizen interest and old official denial

While the Tunisian dialect has preserved many terms of Amazigh origin, those who speak the language constitute less than 5% of the population, or 500,000 people according to the most optimistic estimates and only 100,000 according to UNESCO. .

Mohsen Esseket is from Tataouine and lives in Tunis. He is the president of the Tamaguit Association for Amazigh Rights, Freedoms and Culture. If he does not speak the language fluently, his wife on the other hand masters it and the couple tries to pass on this heritage to their three children. After the revolution, the cultural and identity claims of minority groups resurfaced and several associations were created, taking advantage of civic enthusiasm and newly acquired freedom of expression.

Mr. Esseket then joined the Tunisian Association of Amazigh Culture. In 2016, a new board was formed and Mr. Esseket was no longer a member. He also considers that the cultural aspect limits the field of activities and, in order to be able to commit more to the defense of the civil and political rights of the Amazigh populations in Tunisia, he created the Tamaguit association in 2017. He then devoted himself to the defense of citizens who wish to claim their Amazigh origins, in particular by choosing the first name to give to their children, a thorny issue at the time.

Indeed, a circular dated December 12, 1965 only authorized Arabic first names and the civil status services of different municipalities often made a point of applying it to the letter. The circular published after independence under the presidency of Habib Bourguiba was part of a policy of forced Arabization of the indigenous populations, a significant part of which still spoke Tunisian Chelha, in particular. “ First it was forced Arabization, then the disappearance of Amazigh references in school textbooks in the 1980s ,” laments Mohsen Esseket.

After much controversy, the text was finally canceled on July 16, 2020 by Lotfi Zitoun, Minister of Local Affairs. The latter wrote that the prohibition of certain first names constituted “ a form of restriction of freedom ” incompatible with “ the climate of freedom and responsibility which reigns in Tunisia today ”.

Shy shake of the institutions

Since this small victory for parents anxious to preserve their family and cultural heritage, the political will at the level of the Tunisian State is still very timid. On March 24, 2023, Minority Rights Group International questioned the Tunisian representative on the occasion of the Universal Periodic Review of Tunisia, during the 52nd session of the Human Rights Council in Geneva. “ We declare the urgency of defending endangered Amazigh heritage. Amazigh children and even older people should have the opportunity to be able to learn Tamazight ,” said Cyrine Hammemi, on behalf of the organization.

In the national report submitted by Tunisia to the Human Rights Council and made public in October 2022, the authorities affirmed that from 2024, “Amazigh culture will be integrated into official school curricula, through cultural activities provided by clubs for interested persons ”, ensuring that “ Amazighs [enjoy] their rights in all areas without any discrimination, exclusion or marginalization ”. “ The educational and cultural institutions value the Amazigh cultural heritage and the school aims to root and strengthen this heritage in all its historical and cultural components ”, further specifies the report.

In a column published on the Kapitalis site, Wahid Ferchichi, former president of the Association for the Defense of Individual Liberties and Professor of Law protests against the “ lies ” and “ untruths ” of this report. He thus recalls that there is no official recognition of Amazigh culture and identity in Tunisia and points the finger at attempts at manipulation. “ To say that from 2024, there will be integration of the Amazigh culture in the official school programs, via the clubs, constitutes a manipulation, since the clubs are not part of the school curriculum. Especially since the report does not deal with the Amazigh language which constitutes the main claim of the Amazigh people ”, criticizes the academic.

For Mohsen Esseket, as for many others, learning the language takes place above all at home. “ We have set up language courses thanks to the association, but our means are very limited and we don't know what the State intends to do within the framework of these 'clubs', nor if there will be a adequate funding ”, regrets the president of Tamaguit.

On social networks, the reference to the commemoration of the Amazigh spring in Tunisia is almost non-existent. Chaker Mouelhi lives in Makthar, a city in northwestern Tunisia known for its archaeological site and located on the territory of the Ouled Ayar tribe, a tribe of Arabized Amazigh origin. This photographer, a lover of history and archeology, recalls April 20 almost every year, the anniversary of the Amazigh spring of 1980. “ What remains of the Tafsut n Imaziɣen of April 20, 1980? ”, he wonders this year. Nobody to answer him. “ No doubt the event is still present among some Imazighen, with new identity claims among some Tunisians ,” he reassures himself.

A renewed interest in Amazigh culture and language is, however, noticeable. Thanks to the practice of tattooing or pottery, new generations are discovering a buried heritage. Fairouz Ben Salah, a journalist who has worked on the issue, assures him: “ the young people are taking up the torch a little ”.

Source : websites