The genetic atlas of Paleolithic Europeans revealed

Partial genome sequencing of 356 European sapiens hunter-gatherers confirms some chapters of the Upper Palaeolithic and reveals new, previously unknown ones.

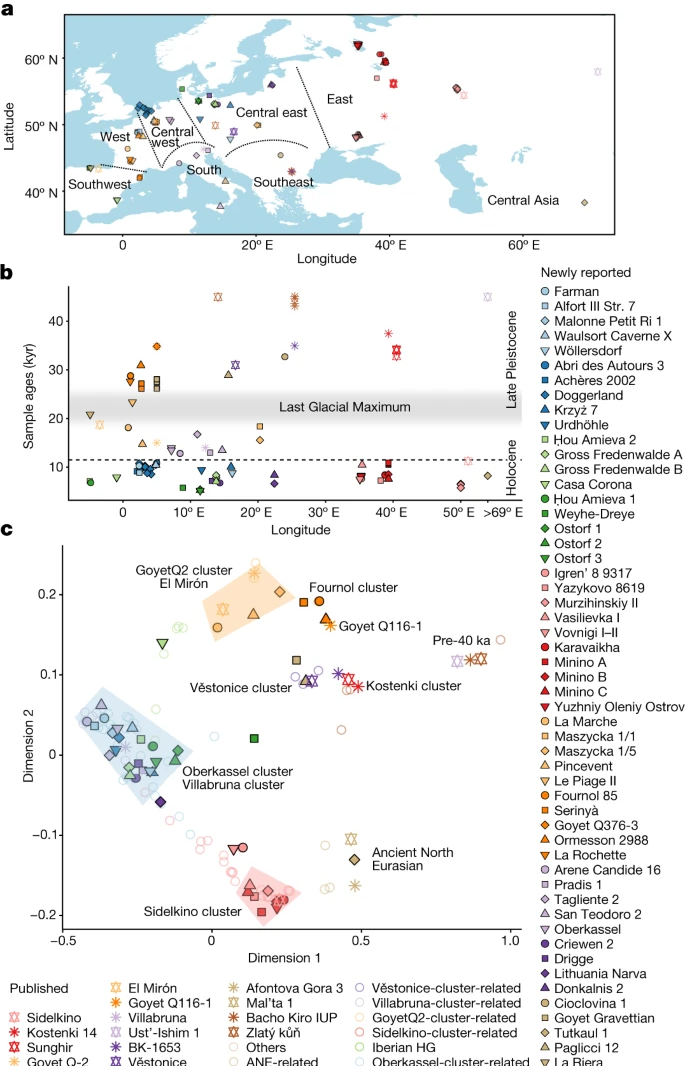

The genetic atlas of Paleolithic Europe is becoming clearer. The team of Johannes Krause, from the Max-Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, has collected the sequences of 1.24 million DNA sites from 356 sapiens hunter-gatherers from several dozen European Paleolithic sites . occupied over the past 35,000 years. After comparing these profiles, the researchers defined several genetic pools – the groups of “Věstonice”, “Fonnol”, etc. –, which they linked to the material cultures practiced by their members.

The researchers' data do not concern the first pan-European material culture - the Aurignacian -, but show that that of the Gravettian (- 33,000 to - 26,000 years ago), which succeeded it, was practiced not by one, but by two populations. , which shared Europe before the last glacial maximum (from - 26,000 to - 19,000 years ago): the Věstonice group (according to the sites close to this Czech village), which populated the current territories of Italy , the Czech Republic and Austria; and the Fournol group (from the shelter of Fournol, in the Lot), widespread in southwestern Europe (France and Spain). While the former were descended from older hunter-gatherers living in the east (Russia), the latter are related to Aurignacians, who lived in the Belgian Goyet cave region 35,000 years ago.

During the last glacial maximum, human populations took refuge in the south: to the west of the Rhône and in the Iberian Peninsula, Fournol developed the material culture of the Solutrean (- 23,000 to - 19,000 years); in the east, the Gravettian tradition persisted until, around 17,000 years ago, groups from the Near East arrived in Italy, founding there the group named Villabruna (after the burial of the Villabruna shelter, in the Dolomites). Progressing southward, the Epigravettian material culture (-17,000 to -10,000 years ago) practiced by members of the Villabruna group reached Sicily around 14,000 years ago, but also spread beyond Italy, since researchers found evidence of Villabruna ancestry in an individual who died 19,000 years ago in El Mirón, Spain.

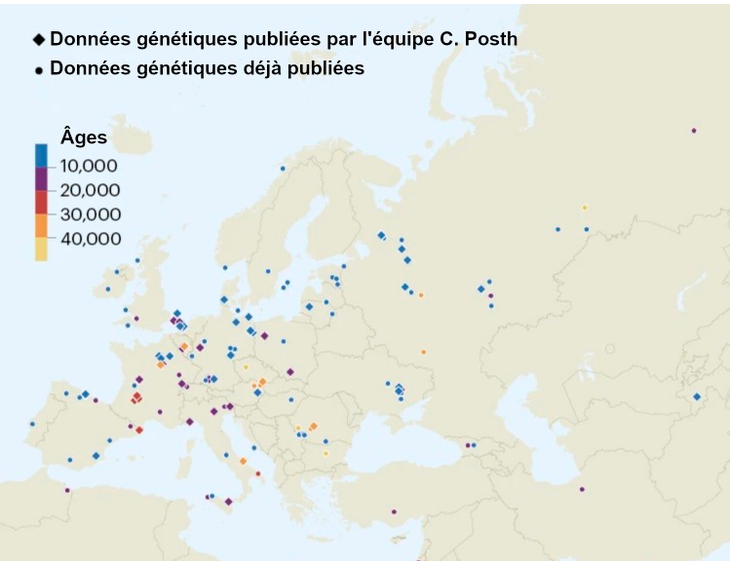

The authors analyzed genomic data from 116 new individuals and reanalyzed previously published data for 240 others. These 356 individuals come from 34 countries.

Nature

The geneticists have also shown that after the last glacial maximum, the populations taking refuge in the south redeployed towards the north, by mixing the genes of the Villabruna and Fournol groups. In present-day France, Belgium, Germany and Poland, these groups gave rise to the population labeled by researchers “Goyet Q2”, associated with the Magdalenian material culture, known for its breathtaking parietal art. Around 14,000 years ago, the complete merger between Villabruna and Goyet Q2 gave the Oberkassel group, which seems to have been homogeneous from Poland to the United Kingdom. We owe him the genetic component from Western hunter-gatherers still visible in the genes of current populations of Western Europe.

Further east, it is another population, whose members had a lighter skin than those of Oberkassel and dark eyes, that we find: the Sidelkino population. It eventually developed the Sidelkino culture in western Russia, while incursions of individuals genetically descended from the Oberkassel group began to reach the Don and Volga region of Russia 8,000 years ago.

Finally, even though the demographics of farmers who arrived in Europe from Anatolia were more dynamic than those of local hunter-gatherers, researchers found that individuals with predominantly Oberkassel ancestry persisted in Germany until it about 5,200 years ago, in the middle of the Neolithic period – a phenomenon already noticed in northern France. This suggests that during the Neolithic transition, some western hunter-gatherers did not disappear but adopted the agricultural way of life, so we may have inherited some of their genes.

Source : websites