Pilgrim Paul Gilot: Memoirs of a Colonial Official on the Hajj Journey

Hajj is more than just a religious ritual. Hajj, as an individual practice, does not depart from the realm of Islamic ritual, but looking at it from afar, as a state of voluntary gathering, limited in time and space, is a “sociocultural” phenomenon that requires contemplation. This attention to it is not new, but is present even in the essence of Islamic jurisprudential thinking, in addition to its solid presence in the social sciences. This huge gathering of people from different sources, origins, and sects has always been, and will remain, a great laboratory for history, geography, economics, and especially for politics. Early on, the French colonialism in Algeria, despite the secularism of the French state, which was deeply secular , turned to the necessity of paying attention to the pilgrimage, from a colonial point of view, whose main goal was more control over the sphere and the population. And an imperial tendency to understand what is happening in the east, especially in the areas of Ottoman influence, which began to recede before the First World War.

This interest is evident in the writings of the French colonial official, Paul Gilot. This document, kept in the French Archives Overseas, is at first a simple administrative report written by, Gilot, in charge of supervising the journey of the pilgrims to Oran between January and March 1905. The value of this document lies above all in the series of photographs accompanying it, and the ability of the writer On description and attention to detail. The report was published by an investigator on the University of Provence, in a book [1] edited by Luc Chanter, who previously published his reference book on “Hajj Politics from the Seventeenth Century to Today,” [2] and Philip Petriat and Lewis Blaine. In this book, Gilot, prompted by evident personal curiosity as well as by a desire to move up the ladder of colonial administration, left us a detailed account of the organization of the pilgrimage to Mecca during the Ottoman era. Bypassing the heavy administrative style of blogging, the writer extends his sources to the press and the archives of the French consulate, interviews witnesses and interviews with local personalities. With the obstinacy of a newspaper reporter, Gilot intends to highlight what he calls "the underside of the pilgrimage": speculation over water prices, return ticket traffic, and local authorities' corruption. The bleak picture he paints of the late Ottoman Empire, and his personal description of the pilgrimage to Mecca, reveal the colonial mentality of the time. While the hundred photos he took during his crossing - reproduced in this book - constitute a valuable testimony to the history of the pilgrimage to Mecca and the circumnavigation in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Paul Gilot was born on November 28, 1857 in the city of Constantine , western Algeria, to a family of black feet . He is the eldest son of lawyer Emmanuel Gilot. He left for France as a young man to obtain a baccalaureate degree and then study law. Then he returned to Algeria in 1877, and performed his military service as a lieutenant in the fourth regiment in Algiers, after successfully passing the reserve officer exam. His family's influence contributed to his early involvement in the ranks of the colonial administration. Appointed assistant apprentice second class in December 1880 in the hinterland of Constantine, he soon endeavored to play on the influence of the family in order to approach the more civilized areas of the coast. After years of local service, he applied for the rank of government commissioner responsible for escorting pilgrims from the Oran district to Mecca to perform the Hajj in 1905.

Since supervising the movement of Algerian pilgrims to Mecca, the French authorities in Algeria have preferred the sea route over traditional caravan routes, such as the famous North African caravan (the Moroccan caravan), which departs from Fez along the southern slope of the Atlas, passing through the coast of Gabes in Tunisia and from there to Cairo and then The Red Sea. For the French, the sea route was faster and safer, and it also allowed them to gain the support of a number of Muslim notables by granting them the privilege of travel. This prompted General Peugeot , the governor-general of Algeria, to organize on six occasions, between 1842 and 1847, an official pilgrimage in order to ensure the loyalty of some notables, and to divert minds from the resistance that was led at the time by Emir Abd al-Qadir .. However, this initiative was abandoned after five years of implementation due to its cost. However, it contributed to familiarizing the colonial authorities with travel management practices, through the creation of laissez-passer passports and the confirmation of the French consular agency in Jeddah, which was established in 1839, as part of its mission to protect pilgrims.

French Consulate in Jeddah

The French colonial policies related to the pilgrimage were governed by two obsessions. A political obsession was mainly related to the authorities’ fear that the Algerians would return from Mecca more “fanatic” - a term frequently used in administrative reports at the time - as if they would be influenced by any anti-colonial discourse in the Hijaz from religious or nationalist grounds. , or simply to take advantage of the ships bound for the Hijaz to flee from lands ruled by non-Muslims. A health obsession, since 1831 the Hijaz has been periodically affected by cholera epidemics that spread during the pilgrimage. Especially the great cholera epidemic in 1865 that swept the Hijaz - leaving between 15 and 30 thousand dead pilgrims - before it reached Egypt and then Europe. Between 1880 and 1905, 17 bans were taken for health or political reasons linked to the plague, cholera, and the climate of insecurity resulting from the fighting led by the Anglo-Egyptian forces against the revolution of Imam al-Mahdi in Sudan.. But on November 26, 1904, after noticing that there were no health risks in the Hijaz, the French Ministry of the Interior finally decided to allow the pilgrimage of Muslims from Algeria.

Once appointed as a government commissioner for the pilgrims of Oran, Gilot commenced from January 23, 1905 writing his report day by day aboard the América, a steamer belonging to the French shipping company Cyprien Fabre. According to French records, the total number of North African pilgrims in that year was about 6,400 pilgrims, distributed among 2,200 Moroccans, 2,326 Tunisians, and 1,866 Algerians. It drives many Moroccans to secretly leave for holy sites. In the same year, about 70 thousand pilgrims landed in the port of Jeddah, including 13 thousand Egyptians, eight thousand subjects of the Ottoman Empire, and 10 thousand Muslims from Central Asia under the tsarist rule.

Pilgrims leave America

Reading the first pages of Gilot's report, it does not appear that the Government Commissioner chose to deviate from the style of writing that governs this type of document. But at the same time, he reveals additional talents in recording observations, diversifying sources, and collecting historical data, photographs, and field testimonies.

Description of Jeddah and its wonders

Particularly at Jeddah, where the steamer America arrives on February 7, 1905, Gilot will exercise his investigative talents. Unlike his predecessors, he does not derive his information about the city from travelogues but rather through observation and first-hand testimonies, and through photographic documentation. Half of the photographs included in the report were taken in Jeddah, where Gilot spent three long weeks in the company of several of his compatriots: the flight officers, the commissioner of the French government and especially Charles Fierre, the director of the French consulate, at which he was resident.

Jeddah Post Office

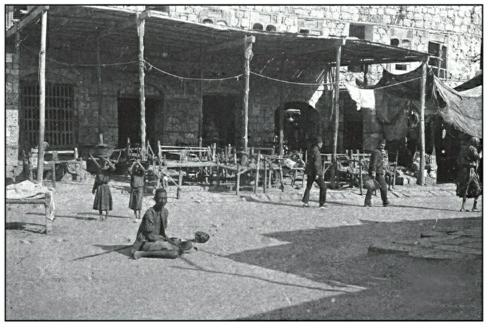

In addition to the rare photographs, Gilot left us a handy map of Jeddah. Through it, we can distinguish the main fortifications and gates, as well as the main public services (the municipality house, the house of the mayor of the city, the civil and military hospital, schools, and barracks). Gilot spent days wandering the streets admiring the houses, which he described as "true jewels", chatting in the many Moroccan cafés he mentioned, or strolling through the souks where, besides the money-changers, there were merchants of cloth, perfume, and so on. He is stunned when he finds German-made toys being imported by Indian merchants. And if the topographical indications and toponymy used by the official are not the most accurate, the photographs accompanying his comments allow us to better understand the nature of life that characterizes the coastal city during the pilgrimage season.

Describing Jeddah, Gilot says:

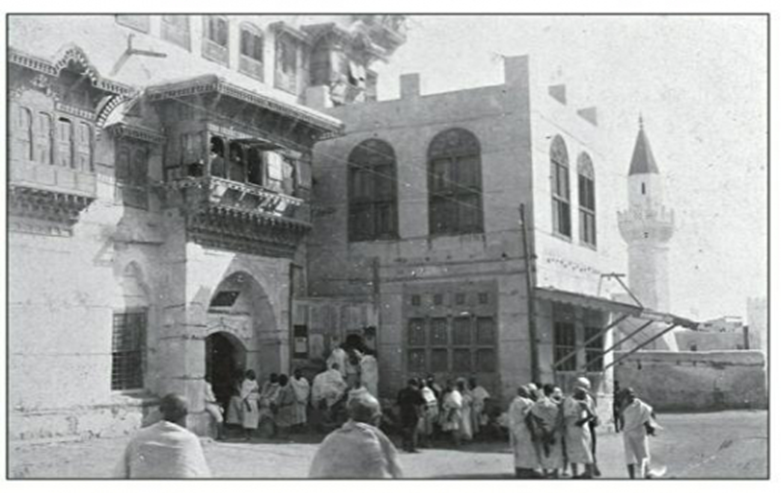

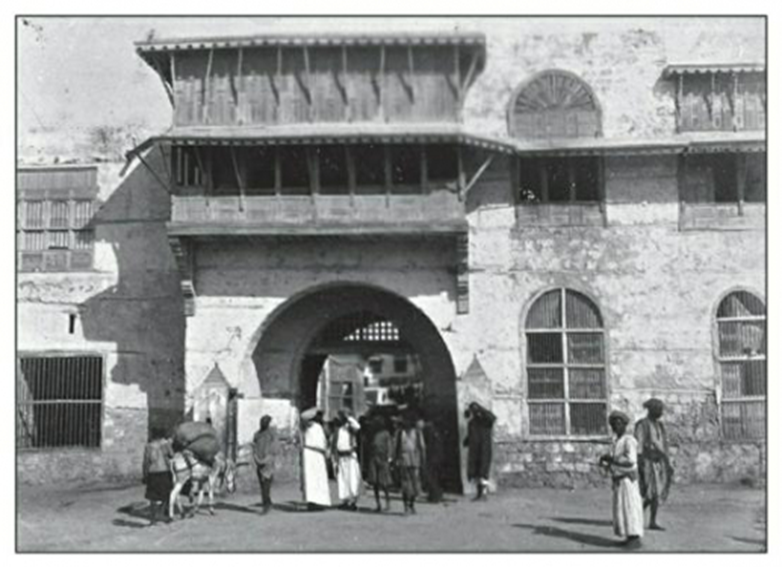

From the sea the city, with its white minarets, makes an imposing appearance: it is surrounded by a square of walls a kilometer on one side with towers and bastions. The first of these forts was used as a barracks for a detachment of Turkish soldiers, and the second became a prison. The city has three entrances overlooking the sea, but two of them are no longer used today. Exiting the health ward, one crosses a huge yard that serves as a camping place for pilgrims on arrival and departure. It is, in other words, the waiting room of the city where pilgrims from all over the world flock to and, it must be said, one of the main centers of infection. One enters the city through the customs gate, over which the Ottoman flag is raised. Three mosques have minarets visible from the sea, and in the absence of signs they serve as a sign, guiding navigators and sailors. As for the inner harbor, it may be one of the most unprecedented ports due to the nature of its formation. It is so well protected from all winds by the reef lines that the sea there is relatively calm even in rough weather. However, to get there, there is only one recognized path. It is the one that passes through a line of coral reefs that we have agreed to call the "middle door", and it is the only door that a ship like the "America" can follow safely.

Customs Gate in Jeddah

Then the writer goes on to describe the large trade movement in the city, based on the data of the French Consulate in Jeddah, and his tour of the markets. Accurately following the nationalities of the merchants and ships that dock successively in the city's port. Nor did he forget to express his admiration for the development of means of communication such as the telegraph, referring to the correlation between the development of trade in any country and the development of communication tools. He also expressed his admiration for organizing the process of supplying the city with potable water, through tanks that transport water from wells prepared for this purpose dug outside the city, although he does not seem satisfied with the quality of the water, which he describes as “very bad and unhealthy”:

“The Ottoman government did great work to bring water to Jeddah. Wells with pumps worked wonders. In Jeddah, there are 200 cisterns outside and around the city. Giant cisterns, amazingly long, high and wide, could contain water to supply the city for two years. My great desire was to measure the capacity of these tanks. All my attempts to do so were in vain. To give an idea of the dimensions of these tanks, here is the information gathered from the driver of the French Consulate, a person worth believing. Suffice it to say that one day we discovered two camels that had been drowned for five months, floating in these waters like two kittens in an ordinary trough.

However, what is remarkable in the report is the abundance of coffee shops in Jeddah at the beginning of the last century. The writer points out that there are a few public squares in which Turkish cafés are concentrated, providing residents with places to meet. There are also a large number of Moroccan cafes in the city, but only coffee and hookah smoking are allowed for ten cents. This forced the owners of the cafes to allocate an internal place for the writer to sit with his French compatriots for lunch and drinking wine, because that is forbidden on the sidewalk. Before that, Gilot had to obtain permission from the customs to pass a quantity of wine, and on top of that, he says, he bribed the customs guards. In the introduction to his report, the writer does not forget to mention that Jeddah is named after the human grandmother, Eve, who is said to have descended from Paradise in that place. So he returns later to this legend after visiting the alleged tomb of Eve in the city.

Turkish cafe in Jeddah

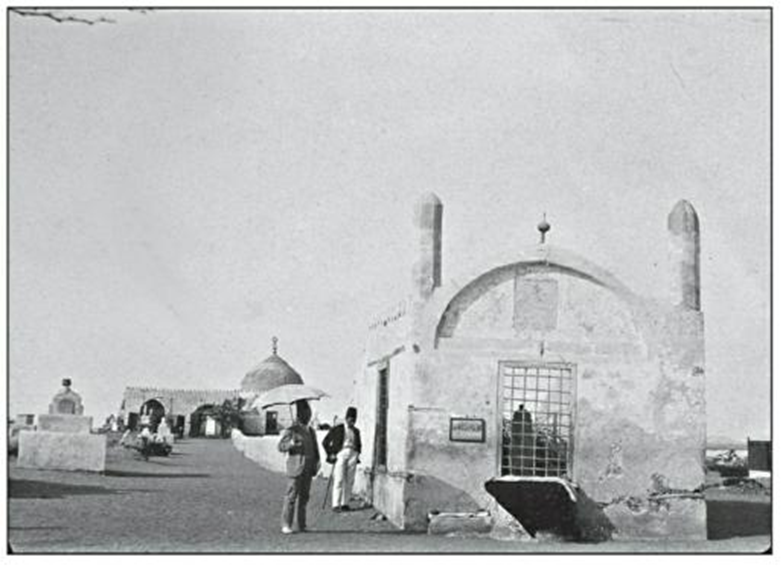

Eve's tomb is located inside a walled Islamic cemetery. A few paces from the front door, between two brick pillars, is a shrine outside which is spread a carpet for offerings. According to the explanation given to us by our guide, there was the head of Eve, and, sixty meters away, a dome representing the navel of the mother of mankind. And a new carpet dedicated to visitors' gifts. Then a third part of the tomb, about 40 meters long, represents the feet. According to legend, our mother Eve would be 90 meters tall.

Eve's grave

Awn Al-Rafiq: The Sheriff of Mecca and his conditions

The Hijaz derives its specificity from an executive dichotomy, formed by the Wali (the ruler of the Hijaz), who is the administrative representative of the Ottoman Empire, and the Sheriff of Mecca, who is a political and religious leader. Gillot describes him as "the great master of Hajj ceremonies." Despite the appearance of Aoun Al-Rafik's pictureIn his report, however, Gilot did not meet him personally and presumably obtained his information about him from the director of the consulate. Sheriff Aoun al-Rafiq was a figure well known to Western consuls who often sought his services. In 1894, the French ambassador in Istanbul described him as "a very strong personality" who makes and breaks rulers. The British describe him as "energetic and cunning". However, his tyrannical nature and arbitrary justice raise many criticisms, starting with his prisons, which resemble the waiting rooms of the afterlife, as described by one of the Bedouins who died in 1902 in the prisons of the Sharif after a clan struggle, and a report of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs dated October 14, 1902. But most of what he records European observers of him are his "shameful greed", in the words of British Consul Cecil Wood. Thus Gilot describes him as "the great broker of regulated brokerage to pilgrims from all parts of the world":

I learned indirectly that the sheriff receives a salary of between 30 and 40 thousand francs a month, and yet the sheriff supplies the Ottoman government, every pilgrimage, with six to seven million. The Mutawafun are completely in his hands, and he also has all the main means of transporting pilgrims (such as sanbuk (small sailing boats) and camels.

Gilot refers to the pressure that the Sheriff's administration puts on the pilgrims to force them to use the services of camel drivers on the road to Medina. In addition to its cost—the rental price of camels would have halved in less than ten years—this overland route is subject to periodic raids by Bedouin tribes. To calm them down, the sheriff made a deal with them to get grain in return for securing the way. The writer quotes an eyewitness from Jeddah as saying, “The truth is known throughout the Hijaz: a third of the booty is kept by the Bedouins, and the other two-thirds are donated to the treasuries of the Sharif.”

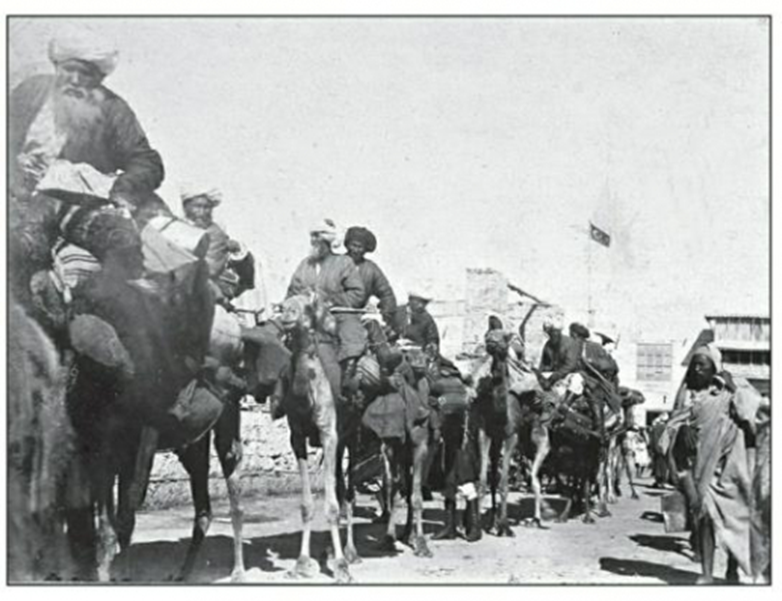

A caravan of pilgrims from Mecca enters Jeddah

A colonial view of the pilgrimage

Throughout the report, the colonial administration's racism and mistrust of the Muslim population emerge. Gilot therefore criticizes some of the pilgrims for their lack of loyalty. The question of the loyalty of Muslim pilgrims is a recurring theme in the hajj administrative literature. In fact, the colonial authorities feared that Muslim pilgrims would take advantage of their pilgrimage, either to escape from French tutelage, or to be convinced of religious discourses that would double their “fanaticism” against the colonizer, or to receive orders for “disobedience” from the Sharif or the envoys of the Ottoman Sultan. This is most evident when it comes to 'protecting' former subjects of the sultan such as the Tunisians, subjects of French colonization since 1881. As Gilot notes:

“Tunisians wishing to perform the pilgrimage are, like our Algerian subjects, obtained a passport which must be approved by the French consul. However, on the 24th of February, the Qaim Maqam, the deputy governor of Jeddah, wrote to the Consul of France to protest in the name of the Sultan and to inform this diplomatic representative that the Sublime Porte did not recognize France's protection over the Muslims of Tunisia.

Indeed, many pilgrims find themselves deprived of any effective protection. Faced with their impotence, the European consuls in the Hejaz are often tempted to appear as defenders of civilization in the face of the supposed barbarism of the East. Reading his report, Gilot is not far from sharing this point of view.

Gilot, who comes from a well-established secular family, is very rational. He finds it difficult to see anything other than a cultural tradition in the pilgrimage, noting that “the pilgrimage to Mecca is an ancient custom that the Prophet retained because it was a means of giving Muslims the opportunity to meet once a year in large numbers and thus to strengthen the bonds of religious brotherhood that unite them.” Such a perception prevented him from feeling the slightest sympathy for the pilgrims he accompanied. When he evokes the joy of pilgrims approaching the holy sites, he likens it to "mental excitement bordering on delirium." When he visits Eve's grave, he tends to be ironic in his feelings and descriptions. Gilot seems convinced that historical development will inevitably reduce Muslim interest in the Hajj. However, history itself will undertake to prove the opposite.

Source: websites