Black and white do not meet in Amazigh marriage

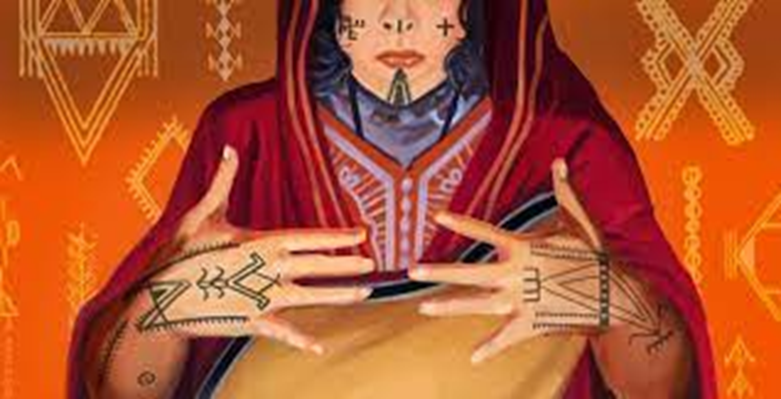

Activists consider that not linking marriage relations between people of white and brown skin in Amazigh regions is not related to color (AFP)

Moroccan tribes forbid intermarriage with people with a different complexion...and observers are calling on the state to intervene

Some societal norms are still imposing themselves in a number of regions in Morocco , which limit the marriage of white-skinned Berbers to each other, as well as Amazighs of dark skin, and the non-exchange of intermarriage between them.

Amazigh activists attribute the continuation of these tribal customs, which amount to the prohibition of intermarriage between an Amazigh tribe and another Amazigh tribe, to the historical heritage of the southeastern region of Morocco, especially with regard to the past of slavery and slavery, which produced these behaviors that are described as racism.

Muhannad Al-Atawi, one of the sons of “Ait Atta”, which is considered a federation of Amazigh tribes in the southeast of Morocco, acknowledges that there are already tribal social customs and norms that prohibit from a long time ago and until today marriage of “mixed color”, that is, the marriage of a black-skinned man to a white woman, and vice versa. Amazighs also have these tribes.

Mohand goes on to say that it is very rare to see a Amazigh couple from the southeastern regions of Morocco, which includes Zagora, Errachidia, Figuig, Ouarzazate, and others, one of whom is brown in color and the other is white in skin, and if this happens, the marriage is not free from troubles and analogies.

He continues his speech by pointing out that there are Amazighs in the southeast who are still stigmatized as slaves, "Ismakhan", "Gnaoui" or "Harnati", given the color of black skin or less black and tend to tan, which are epithets based on color and prevent the conclusion of marriage contracts with Amazigh white color.

The waning of intermarriage

For his part, the Moroccan activist descended from the Amazighs of the southeast, Asou Hansal, believes that the decline in intermarriage and the lack of marriage relations between people of white and brown skin in Amazigh regions is "a phenomenon that is not related to color, as it may seem to some, or to racism based on skin, but rather historical tribal customs." It continued because of the influence of these customs on Amazigh tribes.

According to the same speaker, "this reality represented in the prohibition of intermarriage between the two parties, the emerging generations tried to break its social collar, so young men of dark skin decided to marry Amazigh women of white skin, but there are still few marriages that try to limit these norms that have become unacceptable in the society of the century." Twenty one".

tribal wallpapers

Hassan Amqran, a specialist in Amazigh affairs, comments on these "forbidden" marriages by saying that they are "behaviors that draw from the historical heritage of the southeastern region of Morocco, with all its contradictions, impurities, and accumulated imbalances that are difficult to subject to the balance of reason."

Amqran explained, "These customs and customs flourish more among the Sanhaji branches, especially in the eastern foothills of the High Atlas, where there are many limits that make marriage outside the concentrated clan enter within the circle of forbidden social and tribal anomalies."

He pointed out that "the prohibited mixed marriage does not only concern people of different skin colours, but rather extends it to an incomprehensible concentration on the smaller clan within the same tribe. Ait Yavelman.

Demands to stop spreading the heritage culture that is full of color racism (AFP).

And he went on, "The interpretation ranges between old conflicts sometimes, and coalitions that used to sign the sanctity of blood, sympathizing with the authority of customs," indicating that color is not the only barrier, as some tribes accept marriage with Gnaoui (slaves or Asmkhan), but do not accept marriage with tribes of skin. Less tanned than even the whites themselves.

Amqran concluded that these "closed" positions should not be understood as racist as much as they are a continuation of behaviors with a ossified and rooted tribal background that transcends skin color, tongue privacy, and others, complementing that they are "situations that are not supposed to be given more than their weight in a future world engaged in the sweeping stream of globalization." ".

state intervention

If Amqran believes that these behaviors should not be viewed from the point of view of racism, then the Amazigh thinker and writer Ahmed Assid considers them "negative habits that arose from some deposits of the distant past, and remained latent among the convolutions of the collective mind, framing social relations in some Amazigh regions, although the state It has a completely different logic, whether in its legal arsenal or in its constants and principles, including democratic choice and equality on the basis of citizenship rights as stipulated in the constitution.

He believes that the core of these behaviors is "racism, the origin of which is the past of slavery and slavery, which was considered a legal system in Islam, until the international reference for human rights overcame it and abolished it once and for all. However, the abolition of the slavery system was not accompanied by the abolition of the values and ideas that were entrenched in people's mentality about the dark-skinned person." .

And the number of factors that contributed to the perpetuation of this racist culture, including the absence of national campaigns to educate people against color racism, as the state remained silent about practices that remained circulating in society, and turned a blind eye to racist speech that remained circulating in people's speech, language, and even in their songs and songs.

Another factor, according to Asaid, is the failure of political parties and civil societies to bear their share of the responsibility in combating traditions of discrimination on the grounds of color, and framing society in the values of equality, regardless of belief, color, gender, race, or family lineage.

Another factor was the failure to bring up the values of equality and non-discrimination in books and curricula from the early years of education, and the failure to bring up black-skinned personalities in pictures, pedagogical stands, and televised programmes, in addition to high positions in Morocco and elsewhere.

As for the last factor, Asaid mentions, it is the dissemination of a heritage culture full of color racism and presenting it as literature and poetry without paying attention to its danger to people’s awareness, especially school children. An example of this is Al-Mutanabbi’s poem in satirizing Al-Ikhsheedi’s camphor and demeaning its color, which was included in Moroccan curricula. .

Source: websites