A study reveals the disappearance of the oldest archaeological crater on Earth

According to a new analysis, there's a reason why scientists can't find any fossils older than 2 billion years. It is possible that continuous erosion and geological processes on Earth may have completely erased it from the surface, leaving behind only traces, such as high-pressure minerals and molten rock.

Early scars from asteroids that bombed the Earth's surface may be lost forever to the ravages of time.

Planetary scientist Matthew Hooper of the University of the Western Cape in South Africa says: “It is quite a coincidence that the most ancient structures we have have been preserved at all. There are a lot of questions that we would be able to answer if we had those ancient craters. But this is the normal story in geology. We have to make a story out of what's available."

The early years of the solar system were more turbulent than they are now. There was a lot of space rock flying around, and the inner solar system was taking a big hit. Mars, Mercury and the Moon have surfaces full of craters dating back more than 4 billion years, which indicates this violence.

It makes sense that the Earth was similarly beaten, but the fossil record from more than two billion years ago was blank. Earth has things that Mars, Mercury, and the Moon do not—strong erosion effects and tectonic activity—but Huber and his team wanted to see how effective and efficient these processes were at erasing crater evidence.

And there are ways that scientists can find evidence of craters. The massive impact will alter the mantle beneath the crater floor, for example, which can be detected through gravity mapping and seismic imaging.

Huber and his team wanted to know the amount of erosion from top to bottom to remove all geophysical evidence from the surface.

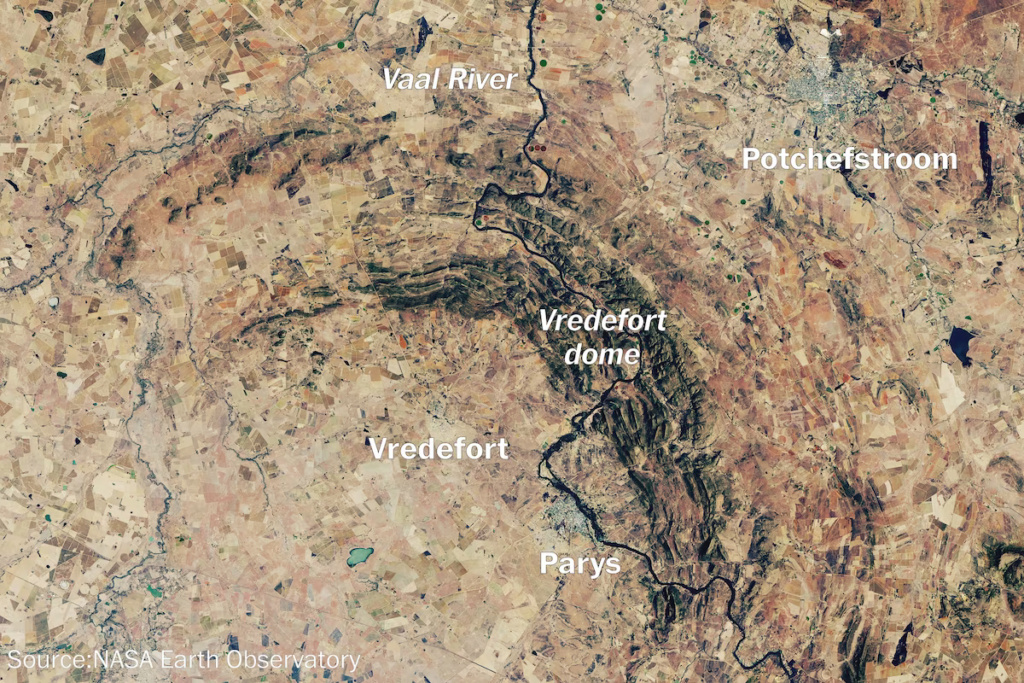

They studied one of the oldest known impact craters in the world, Vredefort in South Africa. It is about two billion years old, 300 kilometers (186 miles) wide, and formed when an asteroid 20 kilometers (12 miles) across collided with Earth. The impact changed the shape of the planet's surface, with a peak in the center due to the rebound and the concentric structures around it.

It is estimated that vertical erosion of about 10 kilometers of material is sufficient to erase even the largest craters. Vredefort saw an estimated 7 to 10 kilometers of vertical erosion. All that remains is a semicircular ring of ridges, some smaller features, and underground modifications not visible in gravity mapping surveys.

Huber and his team wanted to find out what was going on, not above the Earth, but below it, so they took core rock samples from different points in the crater. They modeled the changes the impact would have made on the rocks, and compared their samples, looking for differences in density, porosity, and mineralogy between the impacted and unaffected rocks.

The results showed that the odds are not good for finding ancient pits. Although some impact minerals and melts can be identified within the crater, the rocks in the outer regions are indistinguishable from the surrounding non-impact rocks.

“This was not exactly the result we expected,” says Hooper. The difference, where there was any difference, was incredibly silent. It took us a while to really understand the data. Ten kilometers of erosion and all geophysical evidence of impact disappears, even with the largest craters.”

The team's research has been published in the journal Geophysical Research Planets.

Source: websites