Tamazight Language

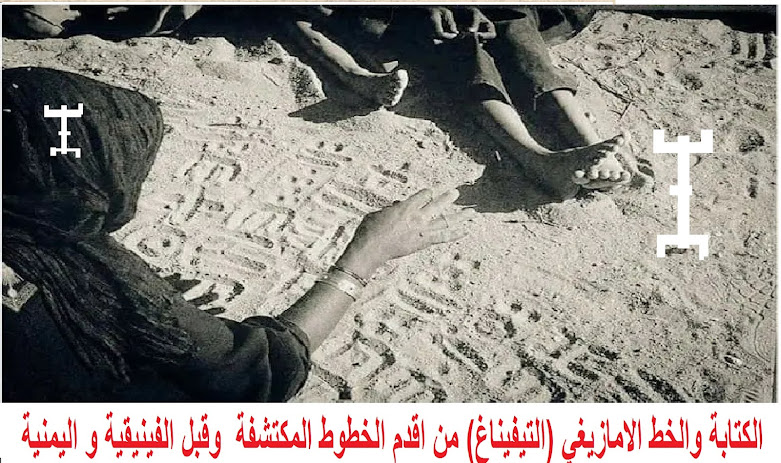

When we talk about the Amazigh language and make it a focus of research and study, we must address Amazigh writing as a carrier of the Amazigh cultural heritage since ancient times. This writing is the foundation of the ontological existence of the Amazigh human being and the true iconic and formal expression of his thoughts, feelings, conscience, and mental, mental, emotional, and kinetic imagination. It is necessary to trace the Amazigh writing and its basic lines to know its civilizational and cultural manifestations and extrapolate its development at the level of blogging and documentation to know the history of the Amazigh person and his intellectual, practical and creative achievements. All of this is because the Amazigh writing helps researchers and students through its well-established inscriptions on caves, rocks, stones and caves. Found in the mountains, valleys, cities, and deserts, through their memorial signs and carpet decorations, and through the phenomenon of decorative tattoos, we can learn about the civilization of the Amazigh people, their culture, their ways of living, and their ways of adapting to the nature that surrounds them.

So, what is Amazigh writing? What are its linguistic and iconic characteristics? What are the most important developments that this writing has witnessed throughout the history of the Amazigh entity? These are the questions that we will explore in this topic.

1/ The Amazigh language family:

It is known in philology that the Amazigh language is one of the ancient languages that belongs to the Hamitic family, along with Egyptian, Berber, and Cushitic. It has been agreed to include them in one group, even though the kinship ties between them are weak, and therefore some consider each branch to be separate and separate. The Berber language is in fact the language of the indigenous people of North Africa (Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Tripoli, the Sahara and the adjacent islands). The most important of them are the Kabyle and Tamashek languages, which are the language of the Touareg tribes (Tuareg).

As for Cushitic, it is the language of the indigenous people of the eastern part of Africa, and it is spoken by about a third of the population of Abyssinia. There are areas in Abyssinia that speak a Semitic language.”

Many linguistic scholars, in their linguistic interventions and research, believe that Berber is a branch of the languages of the Semitic family, while Ahmed Bokos believes that it is “an independent language in terms of genetic relationship with Classical Arabic.” Amazigh belongs to the so-called Hamitic language family, while Arabic falls within the Semitic language family, although these two families share at a higher level within the Hamitic-Semitic family and in the African-Asian family.

Hence, it becomes clear to us that there are those who include Amazigh within the Hamitic family, those who include it within the Semitic family, those who include it within the Japhetic family, and there are those who consider it an independent linguistic entity in itself. Amazigh is one of the oldest international alphabets, along with the hieroglyphic alphabet, the Greek alphabet, and the Egyptian alphabet. It is also one of the oldest alphabets in Africa, along with the Ethiopian alphabet known as Meroitic.

2/ Geography of the Amazigh language:

Enlarge image preview of the original dimensions.

The Amazigh language has been spread in North Africa, or the so-called Tamazgha country, for at least 5,000 years, as evidenced by a group of inscriptions and archaeological documents. Since the dawn of ancient history, the Amazigh linguistic area has extended from the Egyptian borders of Siwa and northern Sudan in the east to the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean in the west, and from Andalusia and Sicily in the north to sub-Saharan countries such as Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. The area of the Amazigh language is estimated at five million km2, and the most important Amazigh group is Which inhabit the Far Maghreb.

The Amazigh language is also found in abundance outside its original area in the Netherlands, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, and the Spanish Canary Islands, which are inhabited by the Guanches who spoke Canarian Amazigh. Before Spanish colonialism eliminated the Amazigh language there. The Guanche still defend the Amazigh language and are seriously seeking to revive it and resurrect it again.

In his book “History of North Africa,” Charles Andre Julien refers to a study conducted by William Marcy that concluded that “the percentage of Berber speakers is 23% in Libya, 1% in Tunisia, and 27% in Oran Province. This percentage exceeded 40% in Al-Aqsa Morocco.” But the matter is nothing more than linguistic differences. There is no greater error than believing - as some have often done - that the division between Arabic speakers and Berber speakers reflects a contrast between an Arab race and a Berber race. The matter only indicates that Berber dialects settled in mountainous areas. It is more difficult for the invaders to find, while in other areas it has surrendered to a language more compatible with social necessities.” It is a national language in Niger and Algeria, but Morocco and Tunisia have not yet recognized it, nor subjected it to the official legal and legal constitution, but it is absolutely and arbitrarily banned in Libya.

The Amazigh language is divided into several dialects: Tamazigh, Tarift, and Tashalhit in Morocco, the Kabylie dialect, the Chaoui dialect, the Beni Mzab dialect, the Beni Salih dialect in Algeria, the Zuari dialect, the Nafusi dialect, the Ghadamsiya dialect, the Awjila dialect, the Sakna dialect in Libya, and the Tuareg dialect in the countries of The Tuareg bordering Algeria, Mali and Niger, and the Siwi dialect in Egypt. As for Tunisia, we can talk about the groups of Sakia, Majura, Sanad, Tamizrat, Chenin, Doueirat and Djerba. The Iznagen or Zanaka group is located on the Mauritanian-Senegalese border.

We can develop another division of the spread of the Amazigh language according to tribes. In general, there are main dialects that can be limited to: Zenatian dialects, Masmoudi dialects, and Sanhaja dialects.

Zenatian dialects are widely spread in Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, and are found in a weaker form in Morocco.

As for the Masmoudi dialects, they are widely found in Al-Aqsa Morocco.

As for Sanhaja dialects, they spread here and there in specific regions in Morocco: the Middle and Far East, and in the southern regions bordering the Sahara.

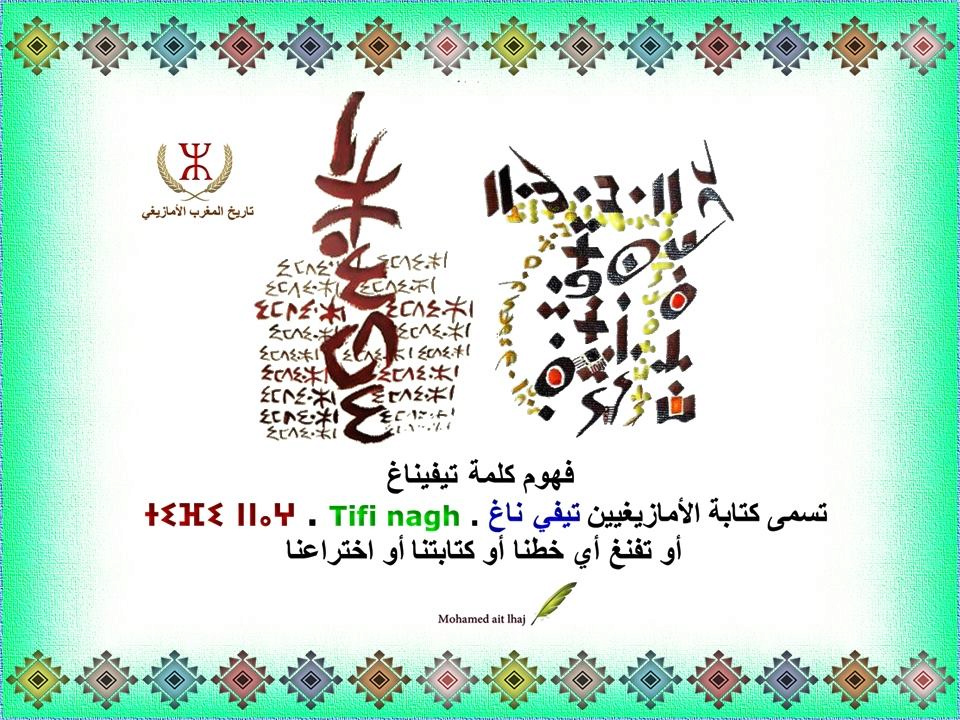

3/ The concept of the word Tifinagh:

The writing of the Berbers is called Tifinagh or Tifinag, meaning our handwriting, writing, or invention. This writing has reached us in manuscript through a group of inscriptions, rocks, and tombstones thousands of years ago, and we have more than a thousand inscriptions on stone plates, or even more than 1,300 texts. On the other hand, some scholars believe that Tifinagh is derived from Phenic and Phenicia. This means that the Amazigh language is a branch of the Phoenician-Canaanite alphabet.

In this regard, Abd al-Rahman al-Jilali says, “The Berbers accepted the Canaanite-Phoenician language when they found it close to their language and because of the ethnic connection between them and the Phoenicians.”

Dr. Ezzedine Al-Manasra believes that the Amazigh language and its alphabet are Phoenician in origin, Canaanite in origin, and Arabic in roots and origins: “The Amazigh language has multiple dialects and is capable of developing into a sophisticated language like Arabic, and its writing in the Tuareg alphabet (Tifinagh) is the origin. The masculine singular is the word (Afniq), which immediately suggests the word Phoenician.” This most likely indicates that the Amazigh language is Canaanite and Carthaginian. The Carthaginian-Phoenician Canaanite was not the language of the invaders, because the Phoenician Carthaginian were the second wave of Canaanites. Since the true origin of the Berbers is that they are Canaanite Palestinians and Lebanese specifically, the indigenous inhabitants of Algeria, the Amazigh Berbers, i.e. the first Canaanite wave, received their Canaanite Phoenician brothers not as invaders, but rather as a continuation of the first wave. It is natural after that that they mixed with the Romans, Greeks and Latins. The original is that the Amazigh language is written in the Tifinagh Towaritic, Canaanite, Carthaginian, and Phoenician letters, and the origin of these letters goes back to the Phoenician Canaanite and the Yemeni Ge’ez Arabic.

However, the word Tifinagh is not intended to refer to Phoenician writing. Rather, we mean writing, calligraphy, signs, letters, or whatever the Amazighs invented.

4/ Characteristics of ancient Berber writing:

A- Amazigh writing in Tifinagh script:

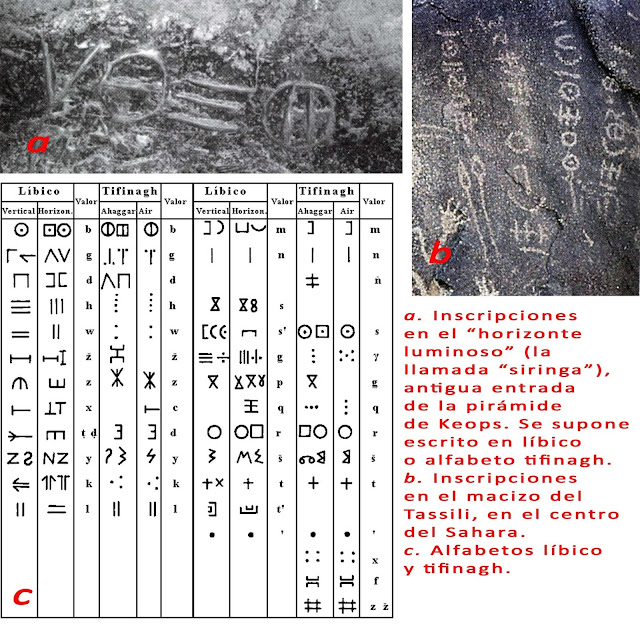

The history of the Amazigh writing (Tifinagh) goes back to distant historical periods that are difficult to determine precisely. There are researchers who date it to 3000 BC, or even to 5000 BC. Until recently, it was believed that Tifinagh was a Phoenician writing that appeared in the second century BC thanks to... Masinissa, but the Algerian researcher was able to find plates with Tifinagh written on them, and the researcher in question here is Malika Hashid, a historian and archaeologist who conducted examinations on the found Tifinagh, and found that it dates back to one thousand five hundred years BC, which made some believe that it was Tifinagh. It is the oldest phonetic writing known to man.

The plaque bearing the Tifinagh letters is one of the plaques accompanying horse chariots. This type of chariot appeared in the era between one thousand years BC and one thousand five hundred years BC, which made Gabriel Camps believe that Tifinagh could not have appeared at a time less ancient than a thousand years before. Birth.

Although there are several hypotheses about the origin of Tifinagh, starting from the Phoenician origin to the local Berber origin, the research has not yet settled on a situation, which is what Gabriel Camps and Karl Presse summarize by saying that despite all attempts at classification, knowledge of the origin of Tifinagh remains elusive.

Hence, Tifinagh is a little-known writing, but it is ancient enough to deserve attention, considering that primitive Tifinagh dates back almost to three thousand years BC. This appears to be Berber writing Which is also called primitive Tifinagh or primitive Libyan writing. It appeared with the Homo sapiens, named after the Tunisian city of Gafsa. So Tifinagh appeared as primitive, readable drawings, and some even made them readable letters.”

The Tifinagh script was used to write on tombstones, caves, caves, rocks, inscriptions, carpets, ornaments, coinage, body tattoos, decoration, decoration, and marking erected historical souvenirs. Although the Amazigh script was used a lot in the valleys and mountains (the Atlas Mountains) and desert areas (the Tuareg countries), it was not used much in the cities due to the dominance of the invaders from the Romans, the Vandals, the Byzantines and the Arab conquerors over their furniture and facilities and naturalizing them in the language of the colonial conqueror.

In its historical path, the Tifinagh script was influenced by Phoenician-Canaanite writing, Egyptian writing, Greek writing, Libyan writing, Latin writing, and Arabic writing, especially at the level of vowels and vowels. Bouziani Al-Daraji believes that “there is some similarity between the (Libyan) Amazigh language and the writing discovered in southern Spain, in addition to the similarity between it and the Etruscan script and other sub-Greek scripts.... Perhaps this is the result of the frictions that occurred across different historical periods. But what is more likely than what was mentioned is The strong connection between the Amazigh language and the Hamitic languages in the first place, then the Semitic languages in the second degree.”

Hence, the Amazigh language in Tamazgha has remained the language of circulation and communication for many Amazighs Despite the policies of integration, Romanization, and naturalization to which they were subjected. They never abandoned their original language, but rather preserved it greatly, especially in areas remote from cities. They also preserved Tifinagh writing, but to a lesser extent compared to the language spoken orally.” It is worth noting that this script - says my teacher, Dr. Muhammad Al-Shami - has never ceased to be written in and is in use. Currently, in a vast area extending from the borders of the Algerian-Libyan desert to Niger and from Hoggar to the borders of Niger-Fultania and Niger-Niger. Even more than this, this Amazigh script has begun to fight illiteracy in Niger, where the Tamazight language has become the official national language among the other Nigerian languages (Tamazight, Bambara, Paul, Sunak) and also in Mali.”

If the Tifinagh script was used to reduce illiteracy in Niger, in Morocco and Algeria it is still used as a “national heritage” after it lost in these two countries its basic function, which is writing, and it became used for decoration and beautification, such as engraving it on bodies as a tattoo or immortalizing it in some artistic images with embroidery. And inscription, and thus we find some “tribal” associations bringing it back to life and resurrecting it again, especially the “Agrau Imazighen” Association, which uses the typewriter to write Tifinagh, and the “Unity of the Amazigh People” Association.”

However, the openness of the Moroccan government, palace and people to Amazigh culture with the Ajdir speech in 2001 AD will give, through the official royal speech, a new impetus to the modern Amazigh lesson, and immediately after this speech the Royal Institute for Amazigh Culture will be inaugurated, which will be approved administratively. Officially, in its sessions, meetings, and seminars, Tifinagh was written as an official script for the Amazigh language, after a great controversy among the members of the administrative council of the institute, especially among those who defended the Latin script, the Arabic script, and the Tifinagh script.

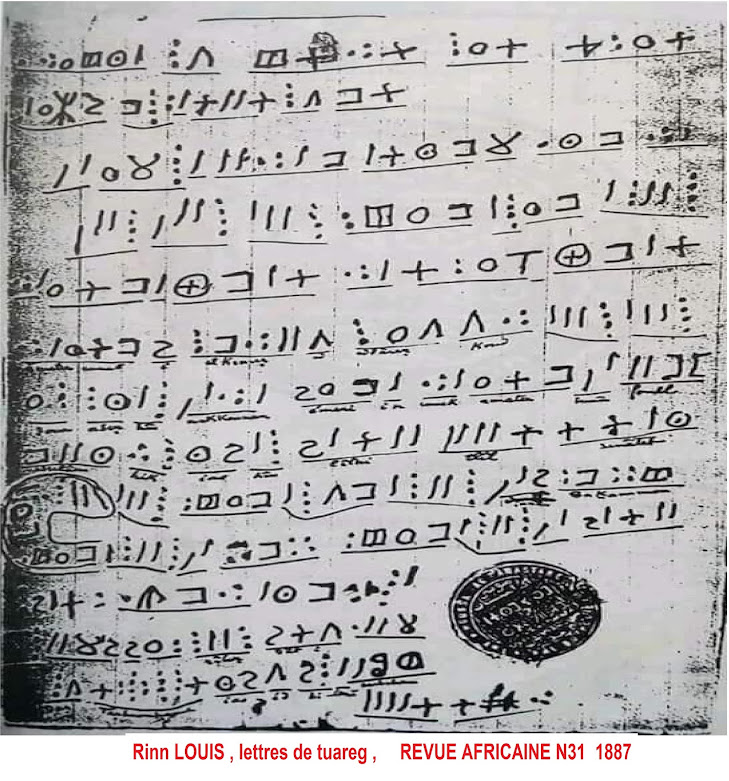

This is how ancient Berber is written, as is known, from top to bottom at the beginning, as is evident in inscriptions, rocks, and caves, to be expanded from all sides, from top to bottom, from bottom to top, from right to left, and from left to right. Writing continued in this form until the late nineteenth century AD, until the Tuareg changed the writing format from right to left, similar to the Arabic language. However, Algerian researcher Bouziani Darraji sees this change He began with the Phoenicians: "In the Phoenician era, the 'Tafeng' script became written from right to left, just like the Phoenician script."

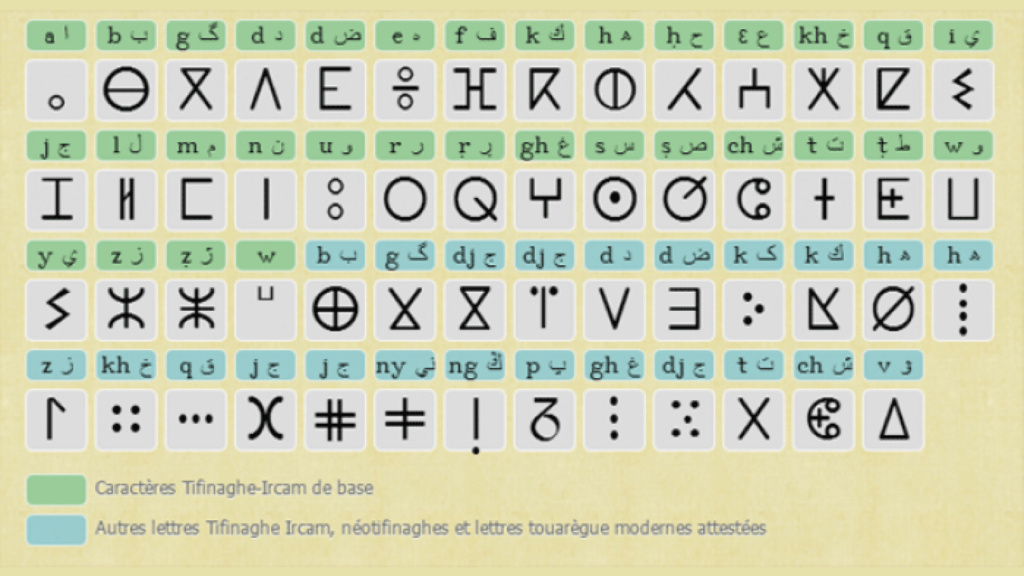

It is known that the Amazigh writing consists of silent and unvoiced letters. It initially consisted of 16 silent letters, Consonnes, and later became 23 letters during the reign of the Numidian Mazilian Kingdom. Some vowels, voyelles, will be added to it with the Arabic fatha of North Africa, and they are called: “Tidbakin.” These vowels are: Fatha, Damma, and Kasra. The Amazigh alphabet is called "Agamak", so today Tifinagh consists of 33 letters, including 29 silent letters and 4 vowels.

One of the characteristics of the ancient Amazigh script is that it is a silent script similar to Idiogramme, which expresses an idea, thing, or image. The line also lacks vowels. This line is prepared in geometric shapes such as circles, triangles, dots, open and closed lines, intersecting lines, and diagonal and various lines.

Moreover, the Berbers in North Africa left us more than a thousand inscriptions on rocks, caves, and stelae, and “they left a number of memorial inscriptions in Tunisia and Algeria in particular, which contain what is accompanied by a Latin or Phoenician translation.” The researcher, George Marcy, made a serious attempt to explain them. But most of the ancient Berber inscriptions are still waiting for specialists who are required to master Berber first, then one of the following dead languages: Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.”

According to the Algerian researcher Bouziani Al-Darraji, the Tifinagh alphabet descended from “an ancient Lubyan alphabet, and it is still in use - these days - within Tuareg circles. It is characterized by being a silent language, and in the beginning it was written separately in all directions: from right to left, and from left.” To the right, then from top to bottom, and from bottom to top. Its letters are not complete yet... This writing, known as Libyan or Lubiyya, was widespread throughout the entire country of ancient Morocco.

Tifinagh writing appeared during the era of the camel. It is known that the Berber man in his activities knew several stages and eras, such as the era of hunters from 5000 to 3500 BC, and the era of shepherds that prevailed from 3500 BC to 1000 BC. The Age of the Horse, which prevailed in the last millennium BC, and the Age of Beauty, the signs of which appeared during the hundred years that preceded AD. As for the era of the one-humped camel, of course, this animal appears in drawings of less quality and artistic perfection than what was known in previous periods, such as the era of hunters and the era of shepherds. This era is also called the Tifinagh period, due to the presence of this writing engraved on the rocks, along with the pictures. Engraved and painted. It seems that this era lasted for a long time, so that the Islamic period can be integrated into it, because some inscriptions began to show Arabic letters alongside the Tifinagh letters.”

B- Amazigh writing in Arabic script:

The Amazigh language was written in the Arabic script starting in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries with Ibn Tumart, who translated the book “The Creed” into the Amazigh language using the Arabic script. However, in the eighteenth century AD, Amazigh writings written in Arabic script would spread, specifically in the Souss region, such as Amazigh poetry attributed to Sidi Hamou Talib and other books of poetry, religion, Sufism, history, and biography. This writing coincided with the Islamic period and the Arab conquests of North Africa, as well as with the influence of Amazigh intellectuals by Muslim scholars in various fields of knowledge, arts, and sciences. In this regard, Ahmed Boukous says: “As for the Islamic period, historians, especially authors of chronicles and biographies, talk about a significant number of references written in the Amazigh language. Including the religious literature of the Kharijites, the Bourgeois, and the Almohads, but most of it has disappeared. We no longer retain anything except some human proper names, place names, and some scattered sentences. Even the poems of Sidi Hamou Talib, which may help to extrapolate the general characteristics of eighteenth-century Berber, some of them have not reached us except through oral narration. Thus, some of the oldest works compiled in the Amazigh language are the work of jurists such as Aznag and Ozal. Perhaps the most famous of these works are the two books of the jurist Muhammad Ali Ozal (Al-Huzali), meaning the Book of the Basin and the Book of the Sea of Tears. The first of them deals with the rules of jurisprudence according to the Maliki school of thought, and the second deals with issues of Sufism. They were composed in the eighteenth century in the Tashalhit language and transcribed in the Arabic script. It is worth noting that the language of these texts It does not differ in any way from modern Amazigh in terms of its morphology, lexicon, and structure.”

The Moroccan Association for Research and Cultural Exchange contributed to issuing a set of publications based on the Arabic script and the “Araten” method of writing. A group of Amazigh associations followed the example of this association in adopting the Arabic script, such as the Cultural Intilaqa Association in Nador, which issued a poetry publication written in the Arabic script.

Among the difficulties posed by writing Amazigh using Arabic script, we solve the problem of writing the hamza and writing the letters with letters, and we see that the “Araten” method is better for writing Amazigh in Arabic.

So here are some Amazigh examples written in the “Aratn” style:

Ezran - Ezran (Poetry)

Yamoth - Yamoth (died)

Amazgone - ــــــامزكان (theater)

Arno Orino (my heart)

C- Amazigh writing in Latin script:

Many scholars and researchers who are proficient in the French language have relied on the Latin script to write the Amazigh product, as we find this clear in many Amazigh associations in Algeria and Morocco. However, the Latin script that was used in issuing a group of newspapers and magazines, such as the newspaper “Agrau”, “Tasafut”, “Toiza”, and the magazine “Tifinagh” by Uzi Ahridane... major changes were made to it at the level of writing to suit the Amazigh pronunciation, so this Latin script became It is distorted by a large number of dots and iconic symbols above and below the head of the letter. Which makes it a difficult script to read if it is not accompanied by a phonetic linguistic table that makes reading letters easier, as we noticed while dealing with a group of rural Amazigh poetry collections, whether published by the “Izoran/Roots” association, such as the collection of Maymoun al-Walid, the collection of Muhammad and the Sheikh, and the collection of Muhammad Shasha or published in Morocco. Such as the collections of Fazima Al-Wariyashi, the collections of Ahmed Al-Zayani, the collections of Rachida Maysa Al-Maraqi, and the collections of Saeed Al-Farrad.

One of the difficulties presented by the Latin script, in addition to its ideological and colonial loads, is that many Amazigh readers do not understand French, and here this urgent question arises: For whom do these people write? Is it for the French audience or for French Moroccans? These French people are in fact a very small elite Or are they writing for Moroccan Amazighs who only master the Arabic language and find it very difficult to understand the French language?! How will they understand a foreign script full of dots and letters that do not express the Amazigh letters in a scientific and precise way? Therefore, it is better to write Amazigh in the Tifinagh script, because it is the symbol of local identity, and the foundation of the inherited Amazigh civilization. Only we must develop and adapt it to keep pace with all technical, scientific, literary, artistic and cognitive developments.

6- Characteristics of modern Amazigh writing:

Picture of the Amazigh alphabet:

The Amazigh script (Tifinagh) is composed and approved by the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture in Morocco After it was recognized by the International Organization of ISOA, it consists of 33 letters, of which 29 are vowels and 4 are vowels. The vowels are formed from four vowels: the fatha vowel - a - (aawal, aman/water), the maddam vowel u- (uwar/the heart, audam/the face), and the sukoon vowel e- (shiya movement), which is used when repeating letters. The consonant (bad / stop, mi / my son, aasrzam / the window), and the kasra vowel -i- (airaf / the pig).

The fasts are prepared in the form of circles and semi-circles, and their number of letters is seven: the Ra (Ibrahim/road), the Ba (Baba/My Father), the Ha (Bohru/Lion), the Sad (Asmaiz/Al-Bard), Al-Sin (Was/Day), and Al-Shain (Awshan). /the wolf), and the aggravated rā’ (barra / outside). There are 11 letters in the form of vertical and horizontal lines: : Nun (aaman/water), jiem (aajana/sky), lam (tamalat/egg), taa (tafukt/sun), mim (tamzida/mosque), dhaa (azair/grapes), and taa (potato/potato). The fa (figar/snake), the waw (awal/speech), the ayn (the pillar/the stick or the pillar), the gheen (the igzar/river), and the dal (adrar/the mountain).

There are four slanted lines, such as the dal (adrar/mountain), the ha (a morning/beautiful), the kha (aakham/house), and the yā (āshafay/milk), and 5 letters in the form of triangles such as the kāf (arqāz), quā (azgāg/red), and the kāf. (Taskurt/Hopscotch), Kua (Itakur/Cursing), Al-Qaf (Aqrab/The Wallet), and two different lines such as Al-Zai (Izi/Fly), and Al-Zai Al-Musaghada (Aazro/Al-Hajar).

It is known that Amazigh writing, as approved by the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture, begins from left to right, similar to Latin writing.

It is noted that when the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture tried to standardize the Amazigh language and unify its teaching didactically and pedagogically, it excluded from its alphabet some of the Amazigh letters found in the rural language, such as the tha’, such as: (thraithmas/a woman’s name), and the letter thaal, such as the sad/road), and the whispering oral letter P, which is considered a letter. An outsider and a distinctive unit in the Berber countryside.

Conclusion:

This is a brief overview of the path of Amazigh writing and its long history. However, this writing requires the Moroccan Ministry of National Education and the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture to teach it to Moroccan citizens in general and Amazigh people in particular. In order to view and read Amazigh productions, this will not be done unless there is a sincere will and good intention to teach the Amazigh language, impose its writing in schools and educational institutions, and train all teachers in it, regardless of their teaching materials, to learn and master them in order to contribute to the process of receiving, assimilating and consuming every Amazigh product, without forgetting to introduce This writing is on personal computers for all intellectuals and learners to use in their communicative speeches.

In addition, this writing can only impose itself by achieving cultural accumulation in the field of production and creativity, using it to label technical and scientific inventions, and using it to issue technical dictionaries and special dictionaries. There must also be intensive collective activity to motivate the Amazigh people to use the Tifinagh script for their purposes and meet their needs, and to introduce it along the lines of the “Tifinagh Caravan,” and the need for the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture to be open to all Amazigh actors without exception or exclusion in order to enrich Amazigh writing, develop it, enrich it and encourage its creativity, otherwise Amazigh language will be destroyed. And write it in the future.

the reviewer :

[ - Dr. Sobhi Al-Saleh: Studies in Philology, Dar Al-Ilm Lil-Malayin, Beirut, Lebanon, ninth edition, 1981 AD, pp. 43-44; - Ahmed Boukous: Amazigh Linguistic and Cultural Politics in Morocco, Tariq Bin Ziyad Center, 1st edition, November 2003, Vidibrant Press, Rabat, p. 15;

- Ahmed Boukous: Amazigh Linguistic and Cultural Politics in Morocco, Tariq Bin Ziyad Center, 1st edition, November 2003, Vidibrant Press, Rabat, p. 15;

- Charles Andre Julien: History of North North Africa, Arabized by: Muhammad Mazali and Al-Bashir Ben Salamah, Tunisian Publishing House, first edition 1969, p. 66; - Bouziani Al-Darraji: Amazigh tribes, Part One, p. 38;

- Muhammad Shafiq: A glimpse of thirty-three centuries of Berber history, Dar Al-Kalam, Rabat, first edition 1989, p. 62; - Abd al-Rahman al-Jilali: General History of Algeria, House of Culture, fourth edition, Beirut, 1980, pp. 30-141; - Dr. Ezz Al-Din Al-Manasra: The Amazigh Question in Algeria and Morocco, Dar Al-Shorouk, Jordan, first edition 1999, p. 69; -See Dr. Muhammad Al-Shami Sad The problem of Amazigh writing)

Proceedings of the first session of the Agadir Summer University Assembly, Fedala Press, Mohammedia, first edition, 1982 AD. - See: (Amazigh language), Wikipedia website, the free encyclopedia, a digital website; - Bouziani Al-Darraji: Amazigh tribes, Part One, p. 35;

- Dr. Muhammad Al-Shami (Sad: The Problem of Amazigh Writing), Proceedings of the First Session of the Summer University Assembly in Agadir, Fadala Press, Muhammadiyah, first edition, 1982 AD, p. 155;

- Dr. Muhammad Al-Shami Sad The Problem of Amazigh Writing), pp. 159-160; - Bouziani Al-Darraji: Amazigh tribes, Part One, p. 35; - Muhammad Shafiq: A glimpse of thirty-three centuries of the history of the Amazighs, Dar Al-Kalam, Rabat, 1989 edition, pp. 61-62. - Muhammad Shafiq: A glimpse of thirty-three centuries of Berber history, p. 62;

- Bouziani Al-Daraji: The Amazigh Tribes, Part One, Dar Al-Kitab Al-Arabi, Algeria, 2003 AD, p. 34; - Bouziani Al-Darraji: same, p. 48; - Ahmed Boukous: Amazigh linguistic and cultural policy in Morocco, p. 37.]