The world's oldest complaint letter is almost 4,000 old years

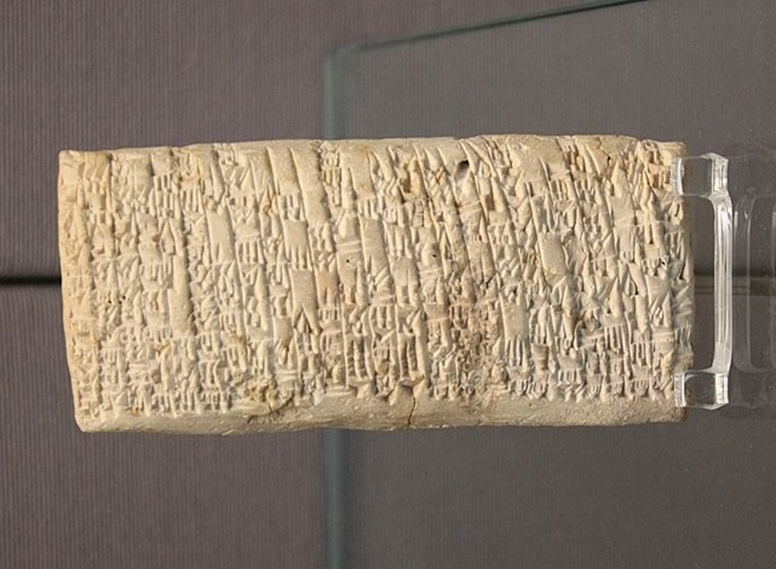

Written in 18th century BCE Mesopotamia by a customer dissatisfied with the quality of his copper order, the Ea-nāṣir Complaint Tablet is considered the oldest letter of complaint in history.

This clay tablet, which bears cuneiform inscriptions almost 4,000 years old, was written by a disgruntled customer wishing to register a complaint following the delivery of poor quality copper. Considered the "oldest letter of claim in the world", it was discovered in what is now southern Iraq, in the house of a metal merchant who, according to his reputation at the time, was unreliable: Ea-nāṣir.

About 3,770 years ago, a disgruntled customer named Nanni sent a letter of complaint to an unscrupulous copper seller, a Babylonian named Ea-nāṣir, following a transaction that did not go through. as expected.

Although this unfortunate situation took place in the ancient city of Ur, in what is now Iraq, several millennia ago, it will speak to today's consumers. Nanni's complaint was even awarded the world record for the oldest letter of complaint by Guinness World Records, and the grievances, four millennia old, paved the way for the creation of numerous memes, comics and comparisons on the Internet.

Who was Ea-nāṣir, and why does Nanni’s letter of complaint continue to resonate with our own experiences thousands of years after it was written?

A DISSATISFIED CUSTOMER

The famous tablet was discovered at Ur about a century ago during an expedition led by the famous archaeologist Leonard Woolley, which uncovered what may well be the house of Ea-nāṣir, as well as a series of commercial documents recorded in the form of cuneiform inscriptions on small clay tablets. Dating from 1750 BCE, the Nanni tablet, now in the collections of the British Museum, is written in Akkadian, the language spoken in Mesopotamia at that time.

The letter, dictated by Nanni, criticizes Ea-nāṣir for having promised him “high quality copper ingots” and for not having respected the contract. According to him, the merchant sent poor quality copper, treated him and his messenger with contempt, and still took his money, probably because Nanni owed him "a (miserable) mina of silver" – one mina equivalent to approximately 5 grams.

When his messenger tried to dispute the quality of the copper with Ea-nāṣir, his request was rejected: “If you want to take them, take them,” the merchant is said to have replied. “If you don’t want to take them, go away!” »

In his complaint, Nanni said he was furious at the poor quality of the copper and the unacceptable treatment meted out to his assistant. “I will not accept any copper from you here that is not of good quality,” he concluded angrily, according to a translator. “I will choose and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I will exercise my right of refusal against you because you have treated me with contempt. »

According to another translation, Nanni gave the merchant a warning: “Because you have despised me, I will cause you trouble!” ".

GLOBALIZATION AHEAD OF TIME

For archaeologists like Professor Lloyd Weeks of the University of New England, who studies the production and exchange of metals in the ancient Near East, this letter illustrates on its scale the realities of the economy of the era.

The copper referred to in the claim was intended for use in the manufacture of everyday objects such as tools, vessels and cutlery, and was therefore an important commodity in Bronze Age Mesopotamia . Located on the Persian Gulf, Ur was a powerful Sumerian city-state as well as a hub of a vast trading network. However, the city did not have significant quantities of the metal, Weeks reveals, so traders had to fetch the copper more than 1,000 kilometers away, in Dilmun, on the island now known as from Bahrain.

To afford this expensive journey, merchants banded together to finance the purchase of copper abroad, each bringing capital in the form of other goods such as silver and sesame oil. These private companies then sold the copper, shared the revenue, and paid tithes and taxes to the palace, and perhaps even to the temples. In his letter, Nanni mentions the payment of 1,080 pounds of copper to the palace, indicating that the Sumerian royalty did indeed demand the payment of such tithes.

Nearly 4,000 years later, this complaint remains relevant. Held together by bonds of class, personal reputation, and mutual need, this ancient global economy was surprisingly complex, thanks to merchants like Ea-nāṣir and Nanni.

“We often talk about globalization as if it were a modern phenomenon,” Weeks continues. “In general, archaeologists and economic historians believe that the Bronze Age is the earliest period in which they can study the effects of globalization. At the time, it may not have extended to the entire planet, but it still affected large regions of Eurasia. »

A BAD REPUTATION

In reality, Nanni was not the only customer to complain about the copper merchant. The British Museum has even more evidence of Ea-nāṣir's dishonest dealings in the metal trade. On another tablet, a certain Imgur-Sin exhorts Ea-nāṣir to “transfer good copper to Niga-Nanna… Give him good copper, so as not to upset me!” Don't you know that I'm tired? ".

The bad reputation of its products had clearly spread around Ur. In another message to Ea-nāṣir, a merchant named Nar-am asks: “Give [Igmil-Sin, Nar-am’s messenger] some very good copper!” Let's hope that the quality of the copper you are responsible for has not deteriorated. »

Given Ea-nāṣir's ongoing customer service problem, it would be interesting to hear Ea-nāṣir's perspective. Remarkable fact: a note from the Babylonian merchant was also found and, unsurprisingly, the latter also refers to problems linked to the sale of copper. In this letter, Ea-nāṣir asks a man named Šumum-libši and a coppersmith not to lose their temper when two other men come to them looking for the missing metal from their order.

“Don’t be critical,” advises Ea-nāṣir. " Do not be afraid ! ".

Great advice from the most notorious conman in the history of the copper trade.

Source: websites