?Who were the first modern humans to settle in Europe

Scientists have identified Crimea as the place where the first modern Europeans settled, using DNA analysis dating back 37,000 years. These individuals showed genetic traces of Neanderthals, suggesting coexistence earlier than previously believed. These discoveries, reinforced by archaeological evidence, highlight the impact of climate change on migration and offer a renewed perspective on the history of humanity in Europe.

The history of humanity is marked by migratory movements which have shaped the face of continents. Among these migrations, that of the first humans in Europe arouses particular interest. Recent genetic and archaeological studies reveal that Crimea was the birthplace of Europe's first permanent residents, 37,000 years ago. The conclusions of the international team, led by the CNRS, are based on the analysis of DNA extracted from human remains found in the Buran-Kaya III region of Crimea, combined with archaeological evidence. These discoveries, published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, by highlighting interactions with Neanderthals, redefine our understanding of human evolution on the European continent.

A mixture of populations in Europe revealed by DNA

Before the stable arrival of modern man in Europe, groups had migrated from Africa 60,000 years ago. However, they didn't stay long. 40,000 years ago, a major climate change took place. It combined with a large eruption of the Phlegrean Fields, near present-day Naples. This led to the reduction of the first European communities.

This research therefore attempts to identify the first modern humans who resided permanently in Europe. To do this, the team studied the genome of two skull fragments from Buran Kaya III in Crimea. They date from 36,000 and 37,000 years ago, as specified in the press release. The authors compared them to DNA sequences from other people living in Europe at that time.

Skull fragment of an individual who lived 37,000 years ago in Bouran-Kaya III in Crimea.

Paleogenomic analysis reveals that they belonged to the second wave of population of Europe by H. sapiens, after the ecological crisis. These individuals, among the oldest European ancestors, descend from a cross with Neanderthals. The genomes of Buran Kaya III show a link with Caucasian populations, corroborating similarities of lithic tools. This suggests a migration from the Middle East, via the Caucasus, to what is now Ukraine.

Remember that in 2011, the team had already made an incredible discovery. The Buran-Kaya III site was frequented by individuals of the Gravettian culture some 32,000 years ago. It is one of the first cultures of the European Upper Paleolithic attributed to anatomically modern Man. They are known for their artistic representations, notably the famous female statuettes called “Paleolithic Venus”. Information which sheds light on the question of the replacement of Neanderthals by the latter in Europe.

Climate shapes interactions between populations in Europe

This coexistence is not just a simple juxtaposition of two species on the same territory. It involves deeper interactions, notably crossings. Genetic traces of Neanderthals in the DNA of modern humans suggest that these two groups mixed. This idea challenges the traditional chronology of human evolution in Europe.

Map shows the genetic relationships between the Paleolithic genomes: Buran-Kaya III (1), Zlatý Kůň (2), Fournol (3), Serinyà (4), Krems-Wachtberg (5) and Věstonice (6). The arrows show the direction of migrations and gene flows and their weight is indicated according to the strength of these flows.

Not to mention that the team's work dated these interactions to around 54,000 years ago. This is much earlier than previous estimates. This period coincides with archaeological evidence showing the simultaneous presence of both species in Europe.

In addition, climate has always been a determining factor in the movements and developments of human populations. Climatic variations (glacial or interglacial periods) have influenced the availability of resources and habitats and migration routes. Researchers suggest that once the climate warmed around 38,000 to 35,000 years ago, people dispersed out of Crimea.

Archeology and culture of the first human residents of Europe

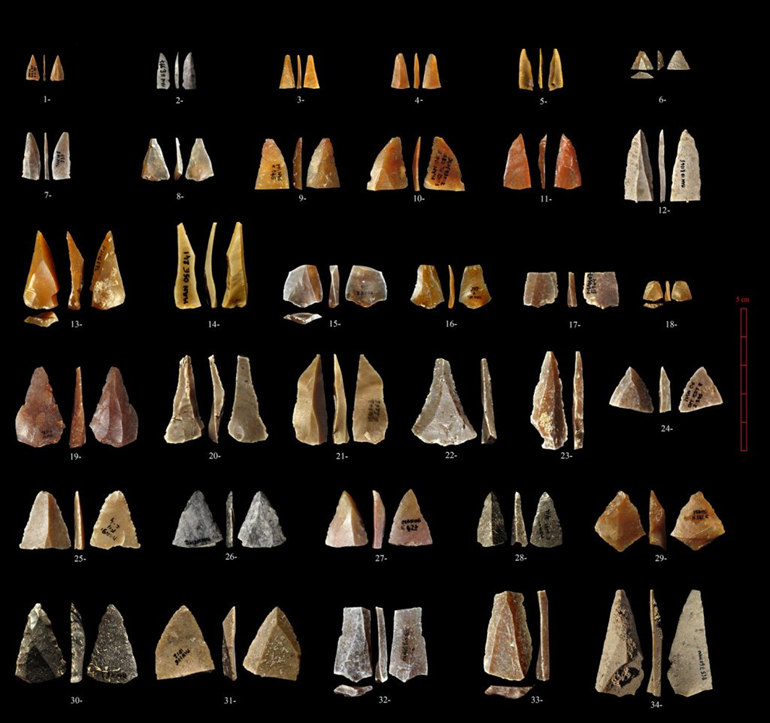

Archaeological evidence, such as tools and artifacts, also show signs of this fusion of cultures. These are all tangible testimonies of the lifestyles, skills and cultural interactions of ancient populations. Even if some point out that the geographical and temporal distribution of tools is deep and broad.

The team of researchers highlighted a certain correlation between genetic data and archaeological artifacts. The stone tools found at Buran Kaya III resemble certain Gravettian assemblages. They argue that the Phlegrean eruption did not cause the complete extinction of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals in southern Europe.

Geigl explains in a Live Science article: “Our results show that there must be survivors of this climate crisis who mated with the newcomers who arrived in Eastern Europe around 38,000 years ago. Therefore, there has not been a complete renewal of the population.”

These archaeological discoveries, coupled with genetic data, paint a complex picture of cultural interactions, movements and fusions. They highlight the richness and diversity of human history on the Eurasian continent. Crimea appears to be a crossroads of human evolution, where different species met, interacted and left a lasting genetic legacy.

The authors conclude in an article in The Conversation: “Our genetic results prove the Ukrainian archaeologists right: the individuals from Buran Kaya III were the ancestors of Western Europeans, producers of Gravettian culture and artists of the famous Gravettian Venuses.”

Source: E. A. Bennett et al., “Genome sequences of 36,000- to 37,000-year-old modern humans at Buran-Kaya III in Crimea”, Nature Ecology & Evolution, October 23, 2023