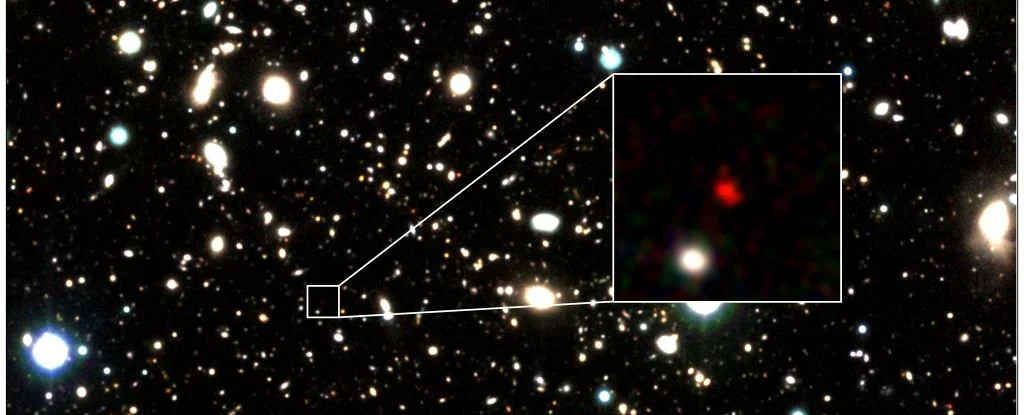

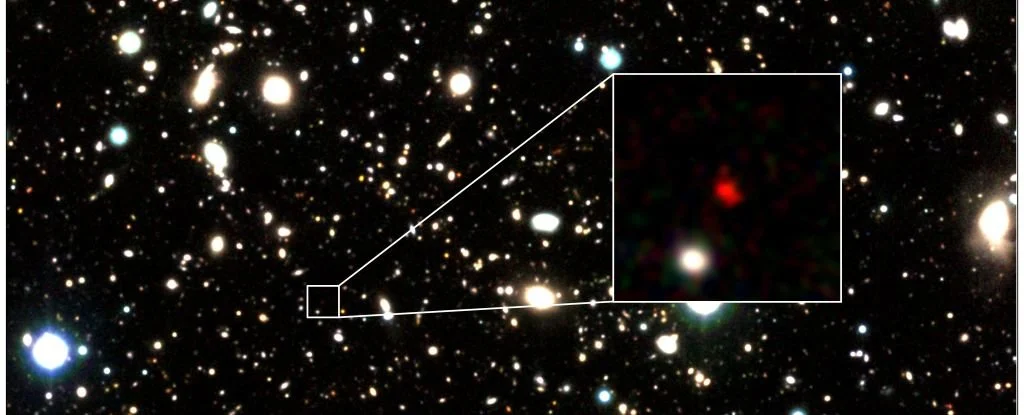

This is the most distant galaxy ever observed

An isolated reddish object in the distant Universe has just been identified as the most distant galaxy discovered to date. According to one study, the structure existed just 330 million years after the Big Bang.

New cosmic record

One of the main goals of cosmologists is to be able to isolate the first galaxies in our Universe and measure their effects on cosmic evolution. Efforts have made it possible to locate some of these very ancient structures, some evolving less than a billion years after the Big Bang. A few years ago, researchers took a new step forward by isolating a massive galaxy that existed 760 million years after the Big Bang. However, all records are made to be broken.

A few weeks ago, a team of researchers would have indeed spotted the glow of an even older galaxy evolving 13.5 billion light years from Earth. In other words, this object called HD1 existed barely 330 million years after the Big Bang.

For this study, the researchers relied on four powerful optical and infrared telescopes: the Subar Telescope, the VISTA Telescope, the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT), and the Spitzer Space Telescope. Together, they have accumulated more than 1,200 hours of observation, peering into the corners of our universe in an effort to identify the most distant sources of light. HD1 finally stood out among more than 700,000 candidate objects.

To calculate its distance, the team then analyzed its redshift. Indeed, the further an object moves from Earth, the more the wavelength of its light is stretched, shifting toward the redder end of the electromagnetic spectrum. So the greater the distance, the greater the red shift.

An object that questions

The light of HD1 is indeed a bit confusing. And for good reason, it shines surprisingly in ultraviolet wavelengths. This suggests that a very energetic process is taking place within it.

Initially, researchers thought it was strong star formation activity. However, the number of stars that needed to form to produce that much light seemed enormous. In fact, more than a hundred would be needed per year, ten times more than expected for a galaxy in the early Universe.

This problem could nevertheless be resolved if these nascent stars integrate the very first generation of stars of our time: those of population III. Indeed, these objects, more massive, luminous and hotter than modern stars, were apparently capable of producing more UV light than “modern” stars. Their presence could then clarify the extreme ultraviolet luminosity of this galaxy.

A second hypothesis suggests that HD1 could be a quasar, the incredibly bright result of an active galactic nucleus explained by the presence of a supermassive black hole frantically devouring matter at its heart. However, to produce the observed light, scientists calculated that this supermassive black hole would have to be at least a hundred million times more massive than the Sun. However, such a size would seriously call into question the growth models of these objects so early in the universe.

Other analyzes to follow

Ultimately, determining the nature of such a distant source will be very difficult, as its light was attenuated in the vast expanses of space-time. “Imagine seeing a ship in the distance, stuck in the middle of a gale and thick fog. From land, you could then try to guess its origin by observing its flag, but you could only see certain colors and shapes of the latter,” explains astrophysicist Fabio Pacucci, of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “Here, it’s a bit the same thing. “It’s ultimately a long game of analysis and exclusion of improbable scenarios.”

The team hopes that future observations with the James Webb Telescope, optimized for peering into the early Universe, will reveal the nature of this mysterious light.

Details of the analysis of this galaxy and a second almost as distant named HD2 will soon be published in The Astrophysical Journal. In the meantime, this work is already available on arXiv, a preprint site.

Source: websites