?!The Japanese and religions... Why don't the Japanese believe in any religion

Religion greatly influences the structure of society and the development of human personality. What does religion mean to contemporary Japanese and what role it has played in the pre- and post-war period? In this article, Professor Shimazono Susumu explains the mystery of the relationship that exists between religion on the one hand and the Japanese on the other.

In 1996, the world of religions scholar Ama Toshimaru published a book he wrote entitled “Why Japanese People Don’t Believe in Any Religion.” This sparked such a wave of reactions that it was translated into Korean and English. According to this book, the reason we say that the Japanese “do not believe in religion” is because we compare it to known religions that have a founder, such as Jesus Christ in Christianity, Buddha in Buddhism, and the Prophet Muhammad in Islam. As for other non-heavenly religions, such as Shintoism and Hinduism, they do not have a known founder, in addition to some popular beliefs for which no founder is known at all. Japanese religions were greatly influenced by these religions. Buddhism entered Japan in the sixth century and was the most influential religion until the middle of the nineteenth century. Buddhism still appears in many and various aspects of Japanese daily life, as most Japanese hold their funeral rituals in the Buddhist manner, which appears in the rituals of performing prayers in front of cemeteries every year and elsewhere.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Japanese religions were greatly influenced by Christianity. Despite the great cultural influence of Christianity through schools and other forms of influence, the number of Japanese Christians does not exceed only 1% of the population of 128 million people. There are some exceptions in Shintoism, where a farmer from Nara Prefecture named Nakayama Miki established a new religion called “Tenrikyo” in the middle of the nineteenth century. Most of the new religions were influenced in one way or another by Shintoism, Buddhism, or both. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Shintoism was an integral part of Buddhism, and the influence of Buddhism was also very great.

Mr. Ama Toshimaru believes in his book that we may be able to see some of the influence of religions that have a founder, but the main basis on which beliefs in Japan are based are natural religions. The Japanese believe in earth and other gods, but without any specific rituals of worship. Thus, the word “no religion” here could mean the concept of Shinto in the broad sense or the concepts of popular beliefs in general. In the beginning there was an influence from natural religions, followed by influence from religions that had a founder but did not take root in Japanese society.

The reason was due to a lack of familiarity and acceptance towards religions that have a founder. Which prompted the answer of the Japanese - when asked about belief in a religion - to be the phrase “I do not belong to them.” Perhaps this is the main point in the book “Why Don’t the Japanese Believe in Religion,” written by “Ama Toshimaru,” mentioned above. Who published this book in 1996. But one year before that, in 1995, there were catastrophic incidents carried out by a religious sect with specific rituals known as (Aum Shin Ri-kyo), which attracted young men in their twenties and a number of university and postgraduate students, in addition to a distinguished elite of doctors, animation and graphic designers, and others. The effect of participating in meetings simply for the sake of worship, and perhaps the Japanese’s lack of belief in any religion, was a major reason for the entry of many students who specialize in the natural sciences.

Mr. Ama Toshimaru explains the existence of “natural religions” by saying that natural religions do not necessarily come from the distant past, as these religions appeared since the appearance of primitive man, then their form developed and Semitic rule was added to them, then they appeared as religions with a founder, and the civilizations of the world were founded on the basis of Those religions. We can say that Shinto is a religion close to natural religions. Before Aum Shin Ri Kyo sparked controversy in the media in the 1980s, the term “spiritualism” was a popular term in Japan. Shinto is linked to nationalist thought in Japan, and it excludes foreigners. But if Shinto were expressed in a spiritual form, the impression of it would be completely different. Shinto is a religion that existed before there was a Japanese state, and this is what most Japanese people believe, but from the point of view of religious scholars, this thinking is merely a way for contemporary Japanese to relieve themselves in the current era from thinking deeply about this issue.

The Japanese and “quasi-religions”

As we mentioned previously, when talking about religions in Japan, we can paint a picture of the Japanese as “do not believe in a specific religion” or “natural religion.” On the other hand, it should be noted that the Japanese, although “religions” are unfamiliar to them, are familiar with “semi-religions.” For example, Confucianism. The Japanese pay great attention to etiquette and bow politely and respectfully to anyone, which is an influence of Confucianism.

In addition, the Japanese use the polite style when speaking with others. Pupils and students at all educational levels speak in a polite and respectful manner with everyone older than them. This is also a characteristic of Confucianism, which is to give “priority to the greater.” Respecting the dead is also a characteristic of Confucianism. We mentioned before that it is from Buddhism, but in fact there is an influence from Confucianism as well. The question of whether Confucianism is considered a religion or not depends on how religion is defined, but we can see religious aspects in Confucianism, such as the reverence for “heaven” and “life” and respect and glorification of ancestors and ancestors. In East Asia, the word “way” or “teachings” is used in contrast to the word “religion” in Western culture. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the teachings of Buddhism and Shintoism were indicated as a “path” that guided people in their lives.

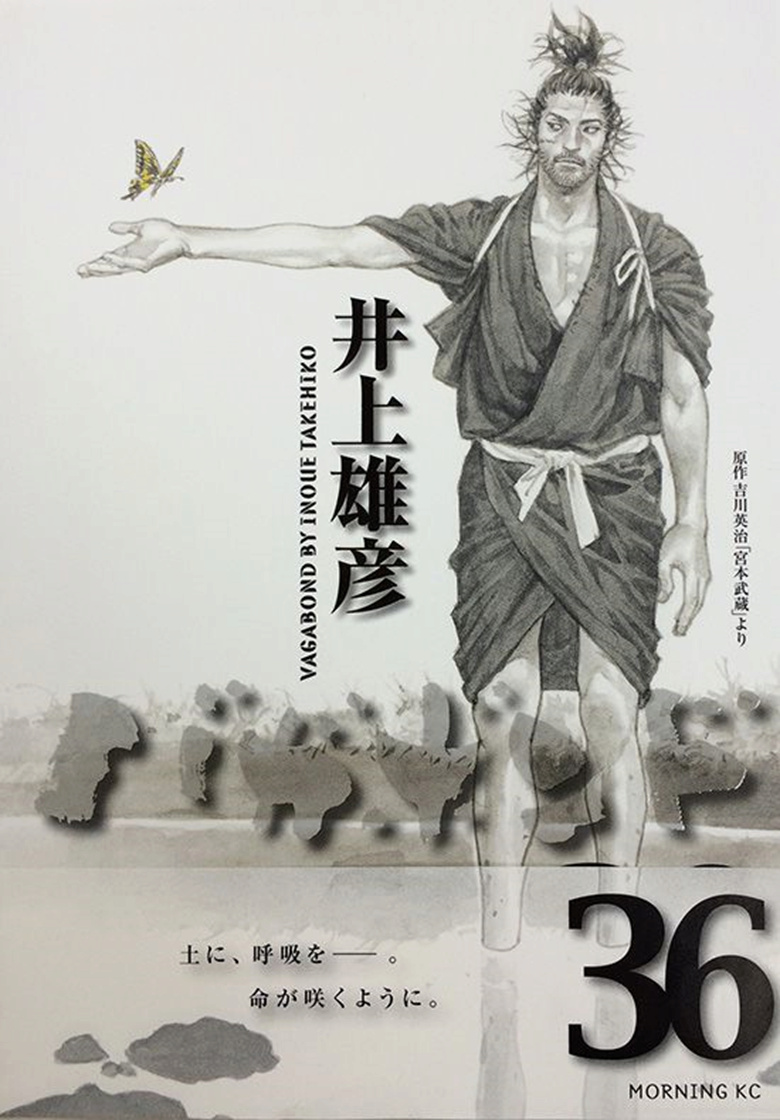

Perhaps the greatest example of Confucianism being a “quasi-religion” is that it disappeared from real society after the reforms of the Meiji era. There are many examples of “semi-religions.” For example, the manga “vagabond” (written by Inoue Taki Hiko and published by Kodansha) published 36 volumes until October 2013. Which began to be published as a series in 1998. Sales of this series have reached about 60 million copies or more in Japan. The story revolves around a samurai knight during the 16th-17th centuries, and its hero is “Miyamoto Musashi,” a person who is skilled in sword fighting and is said to be the person who wrote the book “Bushido.” The original work is a novel that was serialized in a newspaper by Yoshi Kawa Eiji in 1935 and later became a film called “Miyamoto Musashi” that gained great popularity.

“Oneness” appeals to modern Japanese

Perhaps the reason that made the “vagabond” manga popular among contemporary Japanese youth is “loneliness.” The hero of the story is one of the samurai knights, but he has no master, and this means that he is free. The story depicts his life in which he moved away from his hometown and wandered everywhere in Japan, dueling his opponents. The strong and defeated them, so he was fighting with all his strength, and this means that he was ready to die at every moment. The hero of the story does not know the meaning of life, and therefore he searches for its meaning through his duel and fighting with others. He seeks victory over his opponent for the sake of victory, and this point has attracted many contemporary Japanese youth.

There was also influence from the American film “The Last Samurai” in 2003, and thus the popularity of the term “Bushido” has increased in recent years. One of the principles of Bushido is that a person lives every day prepared to fight and sacrifice his life for his master, and this point in turn left an impact in the hearts of many people. Everyone who was searching for the meaning and reason of life tried to extract hints of this from Bushido. Thus, we find that the Japanese are far from what are called religions, but there are many who believe in what is called a “method” or “teachings.” For example, it is known that many students who study in the Department of Religions at the University of Tokyo engage in musical or theatrical activity and the like. There are also those who practice sports activities or martial arts such as aikido and Japanese archery.

There are many people I dealt with who joined the Department of Religions with the aim of delving deeper into understanding the spirit of martial arts. This is not limited to young people only, as there are many elderly people who study things like this at that age in search of psychological stability through study and knowledge. This is a feature of Japanese culture, which lies in the search for spiritual value through something close and tangible.

“National Shintoism” in schools

Thus, to the Japanese there are many things that seem “like a religion” or “a kind of religion,” which makes it more difficult to understand what “religion” actually is. Perhaps the most influential thing in this regard is the Shinto doctrine. Until 1945, compulsory education in Japanese schools was sacred. It included the sacred teachings of the people and the spirit inherent in education, as of 1890 in the era of Emperor Meiji. Thus, schools became Elementary schools were places to learn about the emperor's sacred teachings. The Japanese continued to worship Shinto for decades even after defeat in the war. The image of the emperor was imprinted on them, the obligatory education in greeting the Imperial Palace and Ise Shrine, as well as the pilgrimage to Meiji Shrine and Yasukuni Shrine. This is what is called a Shinto state. We can say that during that period, most Japanese were accustomed to the idea of the Shinto doctrine, which began to spread through schools throughout the country.

Kashihara Shrine in Kashihara City, Nara Prefecture.

Shinto doctrine expanded more into schools than Shinto shrines and temples themselves. It was the day on which Emperor Ham's rituals were held at the Imperial Palace to celebrate holidays before the war, and was not limited only to the National Day of the Founding of Japan. School activities and Shintoism related to the shrines as well as the Shinto Imperial Family served as places for the main rituals of Shintoism, where youngsters were initiated into reverence for the emperor and respect for national political thought, through learning history, ethics and compulsory education.

The origins and history of “National Shintoism”

Perhaps there is a common misconception in the minds of some people about Shintoism, which is that Shintoism resides in the shrine, the priest, and everyone who sanctifies it, but this is only a narrow meaning of Shintoism. In fact, the sanctification or deification of the emperor was the main driving force behind the emergence of national Shintoism in Japan. National Shintoism was practiced outside shrines, in schools, at national events, and in the media. We can say that it is a new and developed form of thought or a national political system that began in the Edo era. It boils down to the fact that the emperor, a descendant of the gods, was sent from the beginning of history to rule Japan sacredly, which later led this thought to believe that Japan is a superior and distinct country over other countries in the world.

As for the history of ancient Shintoism, it is ancient and long, and it is not known when it began. We can say that it began with the beginning of Japan. As for national Shintoism or imperial Shintoism, it is possible to determine when and how it arose. At the end of the seventh century AD and the beginning of the eighth century, Emperor Tenmu ordered the preparation of a religious and legal system for Japan after China, but at that time Buddhism was dominant in Japan, and Shintoism was unfamiliar to the general public, as there was a prevailing idea that it was for the emperors and their families, and then an attempt began to spread it throughout the world. That is, Shintoism was the focus of the state, and this was in the late Edo era and then became the basic idea of the Meiji era.

The pre- and post-war period and the great turning point in national Shintoism

From the Meiji era until World War II, the government (the Ministry of Education at the time) did not consider Shintoism a religion, but rather considered it an ancient Japanese custom or tradition that sanctified and respected the Emperor. Therefore, all Japanese were required to participate in Shinto rituals in schools, temples, or shrines, whether they were Christians or Buddhists. Shintoism began to be treated as a new Shintoism with its own beliefs and teachings. After the end of World War II, the General Command of the Allied Forces noticed the great connection between Japanese militarism and extreme nationalism with the nature of religion, and saw the necessity of separating religion and politics in particular.

She believed that the main reason behind the reckless Japanese aggression was due to religious ideology, and so she thought of erasing the negative effects of that by issuing the so-called “Shinto Order” on December 15, 1945, which was for Emperor Hirohito to confess at the beginning of his speech on January 1. The second, in 1946, is that he is an ordinary human being and not a god. Thus, national Shintoism began to be dismantled, but Imperial Family Shintoism was generally maintained after the war. Relations between Shintoism and imperial Shintoism were subsequently restored, and activities emerged that promoted aspects of national events related to Shintoism. Thus, national Shintoism remained after the war in the broad sense.

Shintoism originally received support from civil movements that linked it to the deification of the emperor, and after the war, these people, including monks, priests, and others, became the main pillar of the national Shintoism movements. Despite their small number compared to before World War II, there is still the idea that Japan is the country of the gods. This is part of freedom of belief and religion, but within limits and provided that this does not affect the freedom of belief of others.

The role of Article 20 of the Constitution with regard to “freedom of belief”

When we look at the history before World War II, we will find that there was no freedom of religion and thought and that all people were forced into nationalist Shintoism, regardless of personal opinion. Therefore, Article 20 of the Constitution guarantees the people’s right to freedom of belief and religion, provided that the state does not side with a particular religion or religious institution, and that religion is not used in political action. The second paragraph of the article also guarantees that no person or any religious institution will be forced to participate in any occasion or celebration related to religion. The third paragraph also stipulates that state institutions shall not practice any type of religious education.

This means that there is no compulsion to submit to national Shintoism, and also clearly that the state does not give Shintoism any special status or powers. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Yasukuni Shrine on December 26, 2013, thus once again raising the meaning or significance of visiting Yasukuni Shrine.

If the Yasukuni Shrine were a public ritual institution, this would mean approaching the pre-war system that led the people to deify and worship the emperor. The role of Article 20 of the Constitution is very important in stopping the strengthening of national Shintoism. The Japanese, despite their lack of familiarity and interest in religions, have a close relationship with society, even in a society that is considered a non-religious society, such as Japanese society.

Source : websites