Sensing the Breeze: A popular festival celebrated by Egyptians

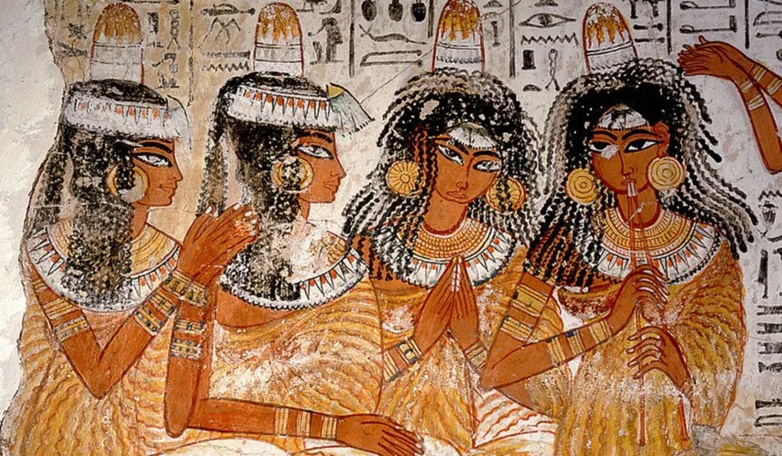

A mural from the tomb of Nakht depicting ceremonial appearances of a group of women to the tunes of a lyre, Dynasty 18, circa 1421-1413 BC.

Ancient Egypt witnessed religious, social, and agricultural holidays. Its celebratory rituals were mixed with special rituals that distinguished it from other civilizations of the Ancient East. Some of them were holidays that disappeared for historical and religious reasons, and others that have lived on in the memory of Egyptians until now, such as Sham El Nessim, which Egyptians have been celebrating for about 4,700 years.

Sham El Nessim is on the list of agricultural holidays in ancient Egypt, and over time it took on a social character related to nature, as is evident from its name “Shammu” in the ancient Egyptian language, hieroglyphs, which is the same word that the ancient Egyptians gave to the summer season, and it also carries the meaning of “summer.” harvest". The word turned into "sham" in the Coptic language, which is considered a late stage of ancient Egyptian writing, but in Greek letters.

While some specialists in the ancient Egyptian language believe that the name “Sham El-Nessim” involves a complete linguistic structure in the ancient Egyptian language, which is “Shammu (harvest) - An (the) - Sam (plant)”, in a clear indication that the Egyptian name has not been distorted. The original inserted the Arabic word “naseem,” which the dictionary defines as “a soft wind that does not move a tree,” to indicate the mild weather and the onset of spring.

Scholars differed in determining a clear and precise beginning for the Egyptians’ celebration of Sham El-Nessim. Some of them believed that the celebration began in pre-dynastic times, according to the division of ancient Egyptian history. Others believed that it dates back to the year 4000 BC, until the majority of opinions settled on considering its official celebration in Egypt to have begun in 2700 BC, with the end of the Third Dynasty and the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty, although these opinions do not deny its appearance in an earlier period, even if In the form of informal celebrations.

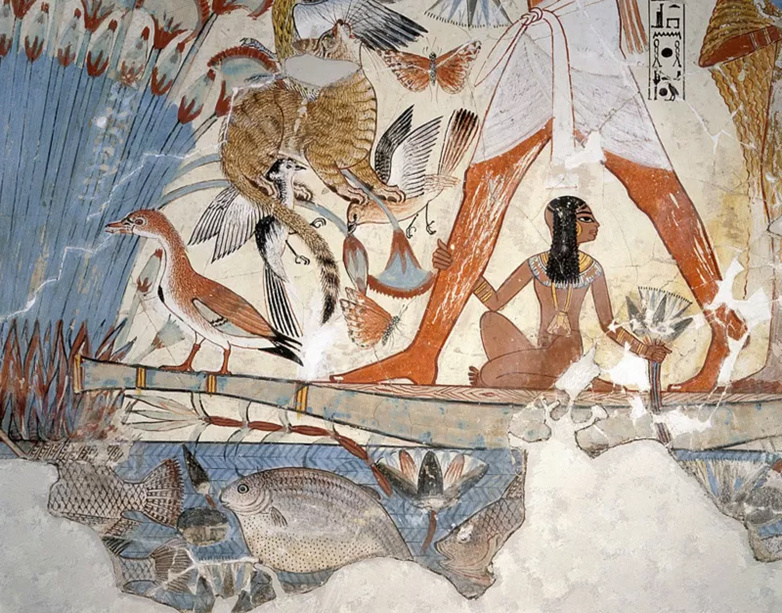

Mural from the tomb of Nebamun standing on a reed boat hunting birds in sedge swamps, circa 1350 BC.

The ancient Egyptian divided the seasons of the year, which he called by the word “Ranbat,” into only three seasons, which were linked to the agricultural cycle on which his entire life depended: the flood season, which he called “Akht,” which begins in the month of July, and the season of sowing seeds. Bert, which begins in November, and the harvest season, Shemu, which begins in March.

The life of the Egyptian in ancient times was not limited to performing religious rituals, devoid of enjoying the joys of life and spreading the spirit of joy. He was keen on more than one occasion to emphasize the concept of joy in his literary texts, such as this excerpt called “Chants of the One Who Strikes the Jungle,” an excerpt that shows the value of... The Egyptian adhered to everything that radiates joy to a person in his life and around his family, quoting from the French translation provided by the scholar Claire Lalouette of the ancient Egyptian text:

“Spend a happy day, put incense and fine oil together for your nose, and place wreaths of lotuses and flowers on your chest, while your wife, who is tender in your heart, sits next to you. Let the songs and dances be before you, and leave worries behind you. Remember nothing but joy, until the day of landing comes.” The land that loves silence.

Sowing and harvesting scenes, New Kingdom era, circa 1555-1080 BC

The ancient Egyptians considered the Sham El-Nessim holiday a new revival of life every year, in which creatures were renewed and nature flourished with all that was in it. They also considered it the beginning of a new, "civil", non-agricultural year, with which they would begin their activities for a new year. The flowers and the spread of greenery heralded the beginning of the harvest season, so they would fill the grain stores with its harvest and offer green ears of wheat to the Creator God during ceremonial rituals, as a symbolic sign of the “new creation” indicating goodness and peace.

The “Sham El Nessim” holiday bore the character of a popular celebration since very ancient times. The Egyptian recorded it in his inscriptions on the walls of his tombs, to commemorate his activity on that day. People would go out in groups to the parks and fields to exercise, and enjoy the flowers and greenery on the ground, carrying the types of food and drink that It was associated with this occasion alone, and the Egyptians have preserved it until now, in an inherited scene that reproduces ancient Egyptian customs every year.

Four young women wearing pleated gowns and wigs with lotus flowers playing music during ceremonial appearances, Tomb of Nebamun, circa 1350 BC

"Food rituals"

Egyptian engravings used to depict scenes showing many tables and foods, sometimes characterized by lavishness, from the upper classes of Egyptian society, such as ministers, priests, senior officials, and landowners. As for the general public, they were waiting for holidays and celebratory occasions to eat all the delicious food and drink they could afford. .

The ancient Egyptian made sure that his menu on “Sham El-Nessim” included a number of foods whose choice was not purely random or purely coincidental, but rather carried a religious and intellectual connotation that was linked to his belief during his celebration of the occasion, including basic foods such as eggs and salted fish (feseekh). Onions, lettuce, and green chickpeas (malana).

Mural of an Egyptian tomb from Thebes, Luxor. It dates back to the eleventh century BC

The egg symbolizes renewal and the beginning of a new creation in the Egyptian religious belief, as it is the source of life, the channel for the emergence of generations of beings, the origin of all creation, and the symbol of all resurrection. The Egyptian called it "Sohat", and mentioned it in the papyri of ancient religious literature when he believed that God "created the earth from clay in the shape of an egg, and the spirit came into it, and life began in it." Therefore, they served eggs on sacrificial tables for their symbolic and religious significance alike.

The importance of the egg also appears in this excerpt from Akhenaten’s hymn, in which he praises the god, quoted from Lalouette’s French translation of the ancient Egyptian text:

“You are the one who gives life to the son in his mother’s womb, soothes her anxiety and dries her tears, provides him with nourishment in his mother’s womb, and gives air so that all creatures can live, and when he descends on the day of his birth, you open his mouth and grant him his needs. And the chick in the nest chirps in his egg, because you are from now on.” Through it, she gives him breezes that give him life and shape him completely, so that he can break the egg shell and emerge, chirping, walking on his feet.”

The god “Ptah” was attributed to being the creator of the egg that brought out the sun, according to ancient Egyptian belief. The egg was a symbol of the sun renewed every day and the source of all life. The Egyptian would engrave his own wishes on the egg and place it in a basket made of palm leaves, so that he would have a view of the god’s light when he arrived. Its radiance is embodied in the light of the sun on Eid every year.

The Egyptian was keen to eat salted fish (feseekh) on this occasion with the beginning of his sanctification of the Nile River, which he called “Haabi” starting from the Fifth Dynasty, in addition to the connection between eating it and doctrinal reasons that implied that life was created from an eternal, limitless water ocean. From Him all beings were brought back to life and established the laws of the universe.

The Egyptians excelled in making salted fish, and they allocated workshop-like places for its manufacture, as evidenced by an inscription in the tomb of the minister “Rakh-Mi-Ra” during the 18th Dynasty. The Ebers Medical Papyrus indicates that salted fish was prescribed for the prevention and treatment of spring fever diseases. And sunstrokes.

The Egyptians attached great importance to eating the onion plant, which they called "Basr", during the celebration of the "Sham El Nessim" holiday, starting from the Sixth Dynasty, because of its connection to an ancient legend that spoke of the recovery of a young prince from an incurable disease that doctors were unable to cure, and onions were the reason for the healing. After the plant was placed under the prince’s pillow, and he inhaled it at sunrise on a day that coincided with the Egyptians’ celebration of the “Sham El-Nessim” holiday, he was cured, and it became a tradition that the Egyptians have maintained until now.

The ancient Egyptian eating of lettuce on this occasion also carried another symbolic and ideological significance, due to the association of this plant with the god Min, the god of fertility and reproduction. The Ebers Medical Papyrus also indicated the benefit of taking it as a treatment for diseases of the digestive system.

As for the green chickpea, known as “Al-Malana,” it was known during the times of the Old Kingdom, and the Egyptians called it “Hor-Bek,” and it carried a doctrinal significance of the renewal of life for the Egyptians, because when the chickpea fruit was full and ripe, it symbolized for him the coming of the spring period, the season. Regeneration and flourishing of life.

"Endless survival"

The ancient Egyptians transferred the celebration of the harvest festival, “Sham El-Nessim,” and its rituals to the civilizations of the ancient East during the reign of King Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) and his military conquests, which contributed to the expansion of the Egyptian Empire geographically and its departure far from the borders of the Egyptian state, and the spread of customs and traditions. Egyptian is alien to these civilizations, so it is destined to continue even if it bears different names.

Egypt promoted its beliefs and celebrations with the same local ideological thought, and the Harvest Festival carried the same concept of renewal of life and the beginning of creation every year in the civilizations of the ancient East, and the peoples of those civilizations considered it the beginning of a new year for the revival of life, as happened in the Babylonian, Persian, and Phoenician civilizations.

Sham El-Nessim is considered the only celebration that has brought together Egyptians with their various religious beliefs for thousands of years, without wearing a ideological guise at all. The historical scene in Egypt affects the mental perceptions that prevailed in the days, after its land remained the first center of all life, the life of the gods and the life of humans, and everything starts from this place.

Lalouette says about ancient Egyptian thought: “Faith penetrated to the depths of the depths of this people, so that the entire universe with its various elements: living or inanimate, human or animal, was a divine universe... Religion is present in every element of ancient Egyptian civilization. It is the religion of hope and hope.” They imagined death as merely a journey to a divine eternity, and they continued to perform rituals that would ensure their endless survival.”

Source: websites