Has Christianity really overcome its long history of disagreement and conflict? How did the church become two churches? (1)

A statue of Emperor Constantine, the first Roman emperor to follow Christianity

With the outbreak of war between Russia and Ukraine, talk spread that it was a religious war on some level, and it was the first time in decades that there was talk of a Christian-Christian war. A few years before this war, specifically in 2017, the Pew Research Center published the results of a research it conducted, and the title was “After five centuries of reform, the Catholic-Protestant divide in Western Europe has faded,” and the editorial stated: “Across a continent that once witnessed wars A long and bloody religious process, both Protestants and Catholics now overwhelmingly express their willingness to accept each other as neighbors, and even as family members.

Is this really true, and is it possible, after long wars, bloody conflicts, victims, grudges, and grudges, to return to peace, brotherhood, and coexistence?

Did the wars between Christians really end and never return? Or is there a fire that - despite the accumulation of ash - is still flammable? Can the current war between Russia on the one hand, and Ukraine and the West behind it, on the other hand, be considered a religious war in some sense, whether between the Russian and Ukrainian Orthodox churches, or between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Western Protestant/Catholic Church?

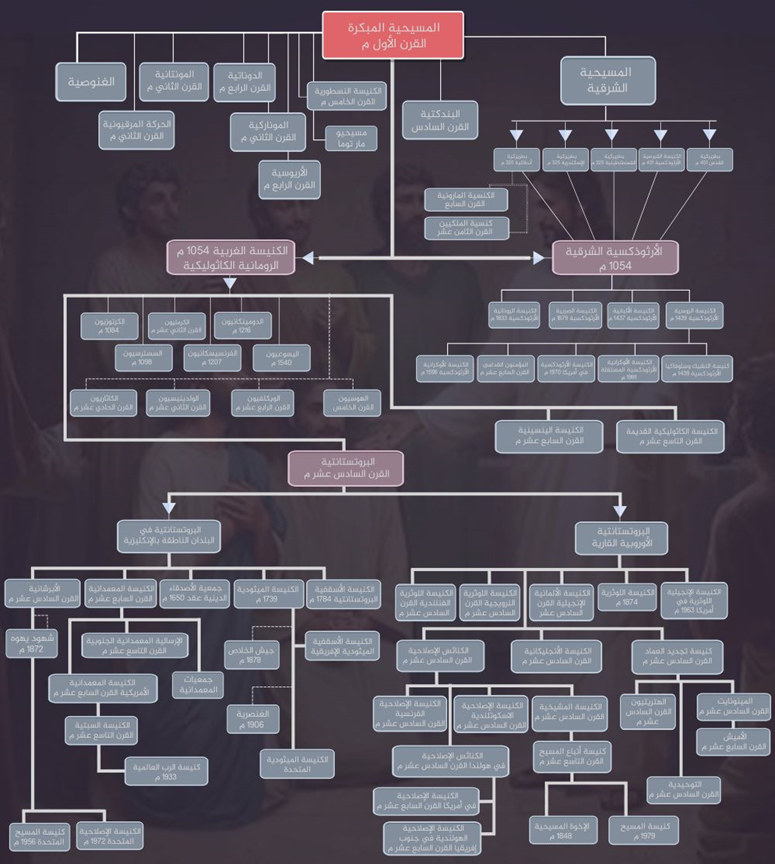

Answering these questions will require lengthy research and a historical foundation, and it is difficult to review it all in one article without the brevity turning into fragmentation or abbreviation, so it would have been better to divide it into parts to be published successively. Today, Christianity is the most widespread religion in the world, with more than 2.4 billion followers. But talking about it begins about 2024 years ago, when - according to Christian literature - a child was born in Palestinian Bethlehem to a humble family and they called him “Jesus.”

To anticipate the future, we must read history

Little has reached us about the life of Jesus, even in Christian references themselves, and all focus is on the last three years of his life, during which he appeared as an evangelist and preacher in various parts of ancient Palestine, its cities and towns. The first followers of Jesus are known to Christians as “the apostles.” They are the apostles, according to the Islamic tradition, twelve men chosen by Jesus himself. They accompanied him on his tours, learned from him, and spread these teachings after him in many parts of the world.

Among these disciples are Matthew, Luke, and John, who wrote three of the four main Gospels that make up the New Testament, which tell the story of Jesus' life, his missionary journey, and his torments.

Speaking about the disciples of Christ, it is necessary to mention “Paul,” whose name was Saul of Tarsus after his birthplace of Tarsus, located within the northern Syrian regions that were subjected to Turkey under the Treaty of Sèvres.

Paul is undoubtedly one of the most important figures in the history of the Christian/Western world. Just a quick glance at the headlines of his life is enough to understand his influence; His works are among the oldest Christian documents that have reached us. He wrote 13 of the 27 books that make up the New Testament, and the Book of Acts of the Apostles is devoted primarily to talking about his missionary works. Many credit him with transforming Christianity from a small Jewish sect into a global faith open to all.

Christianity faced a lot of persecution in the first century. The ruling Roman Empire at that time was a pagan state, and Christianity was considered an illegal religion. The early Christians, including Christ's disciples, faced severe persecution from the Roman authorities, including torture and execution. However, the empire was unable to stop the spread of Christianity. In fact, the persecutions may have increased interest in Christianity, attracting more people to the church, especially since Christianity's message was of love, compassion, and helping the poor and needy, an attractive message to people of all social and economic backgrounds. In addition to emphasizing the importance of hope, Jesus promised his followers eternal life, and this hope was a source of strength and inspiration for many.

In the second century AD, Christianity began to appear more clearly and more broadly as an integrated doctrinal system distinct from Judaism. Communication also increased between the scattered churches throughout the Roman Empire that were founded by Christ’s followers. Roman persecution of them may have played a central role in their cohesion and solidarity. The Church continued to suffer, especially During the reign of despotic Roman emperors such as Nero (54–68), Domitian (81–96), and Diocletian (284–305).

Constantine the Great: a pious Christian or a pragmatist?

It is known that the era of persecution of Christianity ended at the hands of the Roman Emperor Constantine I, who became known as the Great. Specifically when he issued the “Edict of Milan 313”, in which the neutrality of the Roman Empire in matters of worship was declared, and in which the early Church gained freedom and was officially recognized. It is known that Constantine converted to Christianity on his deathbed, where he was baptized by Eusebius of Nicomedia. But what remains unknown, or uncertain, is the reason that prompted Constantine to do all of this, or the main motive behind his sympathy for Christianity and its followers. It is said that Constantine was interested in Christianity from his childhood, as his mother, Helena, was a Christian, and Constantine grew up in an environment Full of Christians. It is also said that politics played a role in this, as Constantine was seeking unity within the Roman Empire. Christianity was a growing religion in the empire, and was popular, especially among the poor and lower classes. Constantine believed that his confession of Christianity would help him gain the support of these groups.

Finally, there is the military/mythological aspect. In 312 AD, Constantine the Great fought a major battle at the Milvio Bridge against his rival Maxentius. Many years later, the Christian bishop Eusebius claimed that the emperor told him that he saw the Christian cross above the sun, just before the battle. Under the cross were the words, “With this sign he conquered.” He has already won.

Regardless of the reasons, Constantine's conversion to Christianity is a momentous event in the history of Christianity, as it helped spread it throughout the Roman Empire and made it the dominant religion in Europe. At the same time, it signaled the intersection of religious and political affairs, an intersection that would later lead to the division of the Church repeatedly.

Official religion of the empire

It was not Constantine who made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, that did not happen until 380 by Emperor Theodosius. But the conversion to Christianity of Constantine, a powerful emperor, legitimized the religion and made it easier for Christians to gain power and influence. In addition, he realized - with the mind of a politician - the necessity of defining the exact nature of the Christian faith, so he called for the holding of what became known as the “First Council of Nicaea” in 325 AD, which was the first of the ecumenical councils (seven according to the Roman and Byzantine churches, and four according to the Eastern Syriac, Armenian, and Coptic churches. ) who formulated and codified the faith, after a major dispute spread over “the nature of Jesus,” between Arius, a priest who lived in Alexandria, who believed that Jesus was created by God, and that his nature was less than the nature of God. While Alexandros I, Pope of Alexandria, believed that Jesus was the “eternal Son of God,” and that his nature was the same as God’s nature.

Alexandros I's opinion prevailed by ballot, and Arius and two priests refused to sign the council's decision. As a result, Arius' books were burned, and his doctrine was called the "Arian heresy."

Although this council was ostensibly religious, politics was present, and its critics even believe that it overshadowed the theological aspect. I think that many have read the famous novel “Azazel” by the Egyptian writer Youssef Zaydan. Although it is fictional, it is based on real events and criticism. Pastor Nestorius of the Council of Nicaea in the novel, an expression of many criticisms of this council, which spoke of the overwhelming presence of Emperor Constantine in it, his great influence on the decisions that were taken, and his clear effort to strengthen his authority over the church, as he did not invite all the Christian bishops, so the decisions were more a reflection of his political desires. It is an expression of the opinions of all Christians.

Of course, disagreements continued, doctrinally on the one hand about the nature of Christ and the nature of the Holy Spirit, and political protocol on the other hand, and no ecumenical council was held later without receiving a large share of criticism, rejection, and disagreements. This topic alone needs pages and books devoted to it, as it is very thorny. Reaching conclusive or decisive results is almost impossible, especially since the factor of time played the role it played in obscuring facts and highlighting others, in addition to the fact that this history of the Church is no different from history in general, that is: it is written by the victors, and there is always another side that it has hidden. The official narrative disappeared little by little.

Chalcedon and the path of increasing division

But in this context, it is necessary to go through the Fourth Ecumenical Council, the Council of Chalcedon, which led to the first real and major division in the Christian Church, and the most prominent of its rejection and results was the Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt, which still believes that Christ is one person in two united natures, two natures. Divine and human nature. The division over this council still exists today, and no attempt to bring the Chalcedonian and non-Chalcedonian churches together has succeeded. Indeed, the gap of disagreement continued to deepen decade after decade and century after century until the Great Schism occurred in 1054.

Before talking about this schism, we must return to Constantine the Great. He not only gave legality to the Christian religion, but he also moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome, the historical capital, to a city called Byzantium. He renewed it and named it after him, so it became Constantinople (the current city of Istanbul).

Constantinople is located in a strategic location on the Bosphorus Strait, which connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. This location gave the empire control over trade between Europe and Asia. The Roman Empire at that time was also facing growing threats from barbarian invaders from the north and east. Constantinople's strong defensive position, surrounded by water on three sides, made it a secure center of government. At the same time, Constantinople was a new city, with no ancient Roman history or traditions, which made it suitable to represent a new era. In addition, it was a suitable capital for the Christian Church as it was closer to Jerusalem, and surrounded by the Greeks who were more accepting of Christianity than the Romans.

Thus, Constantinople became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, or what was called the “Byzantine Empire,” and the division began to make its way into the huge empire, and it did not officially occur until the year 395, after the death of Emperor Theodosius I. Although the fall of the Roman Empire occurred in the year 476, Byzantium lived for more than an additional thousand years, until it fell at the hands of the Muslims in 1453.

The inhabitants of Byzantium in the Islamic world were called "Rums", a name later adopted by the Eastern Christian sects that followed the Byzantine rite.

The division of the Roman Empire and the division of the Church

After this division, Latin-speaking Rome began to claim supremacy over Greek-speaking Constantinople, and disputes arose over church boundaries and control.

When the Western Empire disintegrated in the fifth century, it was invaded and ruled by Germanic tribes, and this caused the social, cultural and political structure of the West to rapidly diverge from that of the East. Communication between East and West was further hindered because while the language of the East tended to be Greek, Latin was the language of the Church in the West.

Rivalry developed in the Slavic regions between Latin missionaries from the west and Byzantine missionaries from the east. Disputes over authority became more heated in the eleventh century when the Church of Rome asserted its primacy over its four sisters in Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem (mostly because it was founded by Saint Peter, who was the disciple closest to Christ, and because of the importance of Rome in the Western mind, which saw it as More like the center of the universe.)

In this context, it is necessary to go through a very important event, which is the assassination attempt on Pope Leo III, who was Bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 795 until his death in 816. The Pope fled to Germany, where he met Charlemagne, the German king, or The Franks, as the Arabs called them, and asked for help in regaining his power. Charlemagne agreed to this and in the following year, 800 AD, he led an army to Rome, helped the Pope, and installed him on the papal throne. In return, the latter beatified Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor. Charlemagne appeared as the legitimate heir to the Roman Empire, equal to the Emperor of Constantinople, and the institution of the papacy in Rome appeared as having the right to grant temporal authority to kings and emperors.

The Pope of Rome took advantage of this power and gathered under his leadership all the churches of the West under the umbrella of one Catholic (i.e. universal) Church, in contrast to the Eastern churches that were called Orthodox. The word Orthodox goes back to Greek. Its first part is derived from the word “orthodox,” which means “correct, correct,” or upright, and its second part is derived from the word “doxa,” which means “opinion” or “belief,” and it is linked to the word Dworkin and its meaning. “He thinks.” Its members used this term because it meant the straight path to the glory of God, far from what they considered to be doctrinal errors that had begun to appear in the Western Church.

So, tensions had been there for centuries, but the actual schism was set at 1054, because it was in this year that Patriarch Michael Cerularius of Constantinople and envoys of Pope Leo IX excommunicated each other. The complete exile came a century and a half later, as a result of the Crusades, when Christian knights launched military campaigns against Muslims in Jerusalem, and in 1204 the Fourth Crusade was transformed to attack Constantinople and brutally seize it. Thousands of Orthodox Christians were killed, churches and icons were desecrated, and endless hostility arose between East and West.

Hostilities will follow, and the divided will be divided again, in the West, which was wandering in the Dark Ages, before the East, and the Catholic Church will assert its authority and influence over all of Europe, until a German priest named Martin Luther comes and says “no” to what he considered financial, moral and ideological corruption in... the church.

This priest's revolution and its results will be the subject of the second part of this article.

He follows...

Source: websites