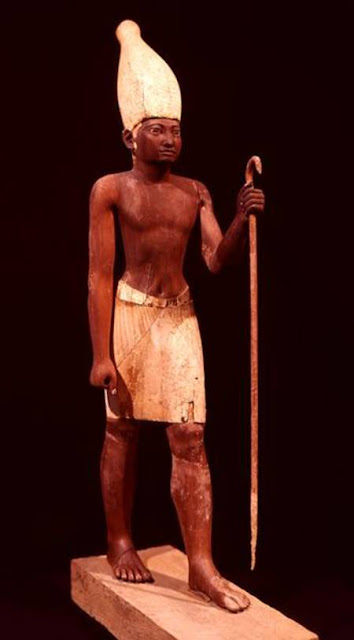

At the Cairo Museum, a statue of Sesostris I from Lisht

Statue of Sesostris I discovered between March and May 1914 in Lisht

in a room in the surrounding wall of Imhotep's tomb

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition led by Albert Morton Lythgoe

Egyptian Museum in Cairo - JE 44951

If Lisht is, today, the name of a small village located 60 km south of Cairo, it is from this place that, during a certain period of antiquity, Egypt radiated. Indeed, this location was chosen by Amenemhat Iᵉʳ, founder of the 12th dynasty (around 1985 -1773 BC), to establish the new capital of his kingdom. Tj-Taouy (literally "Amenemhat-seizes-the-Double-Land") was created, "obviously ex nihilo, to house the Royal Residence in place of Thebes where until then the pharaohs of the 11th dynasty sat".

The royal necropolis attached to it houses, in addition to the funerary complex of its founder, that of his son and successor Sesostris I.

This complex is made up of its own pyramid, as well as nine other, smaller ones, dedicated to queens and princesses. Beyond the surrounding walls are numerous tombs of high officials.

The site was excavated, summarily, in 1882 by Gaston Maspero, then more extensively, in 1894 and 1895, by Etienne Paul Joseph Gautier and Gustave Jquier of the IFAO. It was then "invested" by the Metropolitan Museum. For nine seasons - between 1907 and 1934 - the excavations there were directed by the museum's curator, Albert Morton Lythgoe, as well as Ambrose Lansing and Arthur Mace.

Between March and May 1914, A.M. Lithgoe "rediscovered" the large funerary complex of Chancellor Imphotep which had only been partially excavated in 1894 by Gautier. Investigations undertaken south of the surrounding wall led to the discovery of this extraordinary statue of Sesostris I.

Carved from cedar wood, it is 56 cm high and 26 cm wide. Placed on a parallelepiped base, it "represents a pharaoh in movement. While his right arm is stretched along the body - his hand must have held the now lost Kherep scepter - the left is folded forward with, at the hand, a long stick whose curved end recalls the shape of the heqa scepter" analyzes Rosanna Pirelli in "The wonders of the Egyptian museum in Cairo". Isabelle Franco defines this royal scepter as being "an Osirian attribute in the shape of a crozier that the sovereign receives among the insignia of power".

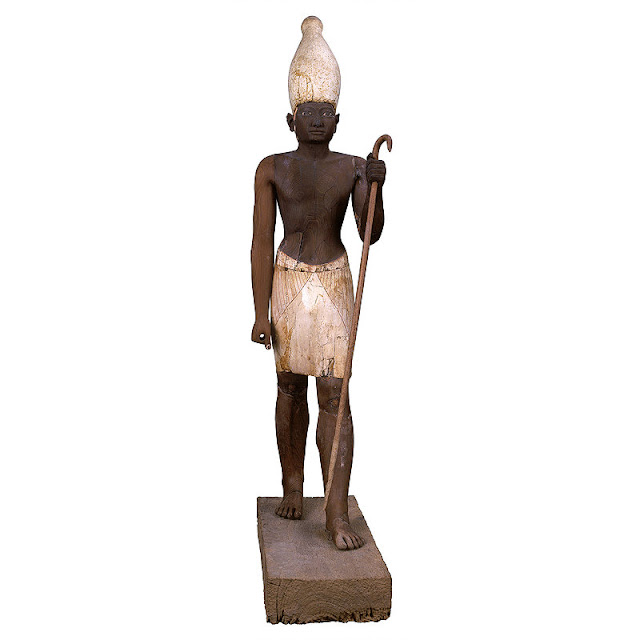

Statue of Sesostris I discovered between March and May 1914 in Lisht

in a room in the surrounding wall of Imhotep's tomb

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition led by Albert Morton Lythgoe Egyptian Museum, Cairo - JE 44951

The king wears the white crown of Upper Egypt. His face is admirably worked. The eyes are large, deep, "drawn in curved lines extending towards the temples and made particularly vivid by the white cornea and the dilated black pupil; the gaze is slightly directed downwards" (Rosanna Pirelli).

The ears are well defined, the nose is of good proportions and the mouth is rather small... "According to a circular hole made under the chin, the face was adorned with a ceremonial beard" specify Mohamed Saleh and Hourig Sourouzian in their " Official catalog of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The body, nicely muscular, is harmonious. The shoulders are square, the waist, at the exposed navel, is slim. The legs are thick, the feet are bare.

Statue of Sesostris I discovered between March and May 1914 in Lisht

in a room in the surrounding wall of Imhotep's tomb

by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition led by Albert Morton Lythgoe

Egyptian Museum in Cairo - JE 44951 (photo of the museum)

The king wears a short loincloth "with both ends raised towards the belt; it is covered with a stucco coating and then painted white, with details traced in ocher" (Mohamed Saleh and Hourig Sourouzian).

The entire body was painted brown and the charm of this statue also lies in this striking contrast between this dark color and the lightness of the crown and the loincloth.

The statue is made up of several parts which were worked separately and then joined together using tenons.

In the deposit discovered by A. M. Lithgoe, this statue was not alone. Indeed, it had its "counterpart" another almost identical statue, with the difference that it wore the red crown. Oriented "facing east, they stood side by side behind a small wooden naos".

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York provides the following explanation: "A room had been set up in the southern part of the surrounding wall and the statuettes as well as the sanctuary were hidden there, undoubtedly after having played a role in a ceremony funeral".

"Guardian Figure" découverte entre mars et mai 1914 à Lisht

dans une chambre du mur d'enceinte de la tombe d'Imhotep

par l'Expédition du Metropolitan Museum of Art dirigée par Albert Morton Lythgoe Metropolitan Museum of Art New York - Accession Number : 14.3.17 (photo du Met)

Lors du partage des fouilles, les statues qui reposaient ensemble depuis plus de 3800 ans furent séparées. Celle à la couronne blanche symbolisant la Haute-Egypte a rejoint le musée du Caire où elle a été enregistrée au Journal des Entrées sous la référence JE 44951.

Quant à la seconde, portant la couronne rouge symbolisant la Basse-Egypte, elle est partie vers le Metropolitan Museum of Art de New York où elle est exposée sous le n° d'entrée 14.3-17.

Il y a lieu de préciser que ces deux statues anépigraphes sont généralement attribuées à Sésostris Ier parce qu'elles ont été trouvées près de sa pyramide. Cette "attribution" a été retenue par le Musée du Caire alors que le Metropolitan Museum présente la sienne avec plus de "réserve" comme "Guardian Figure", précisant que son "visage semble refléter les traits du roi régnant, très probablement Amenemhat II ou Sésostris II".

marie grillot

sources:

Egyptian Museum in Cairo - Standing statue of King Senusret I

https://egyptianmuseumcairo.eg/the-collection/page/3/

The Metropolitan Museum of Art New York - Guardian Figure

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/543864

Peter F. Dorman, Prudence Oliver Harper, Holly Pittman, Egypt and the Ancient Near East, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), 1987

https://books.google.fr/books?id=a08kkuWhv7wC&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y&hl=fr#v=onepage&q=bahari&f=false

William C. Hayes, Scepter of Egypt I: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge, Mass.: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 192, fig. 117, 1953

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_Scepter_of_Egypt_Vol_1_From_the_Earliest_Times_to_the_End_of_the_Middle_Kingdom?fbclid=IwAR3C3MQZlsj_PIWEfnEqB5MwfBDjZcJhMEwOr8s9ijRwtXrOZWepwlAY-5M

Jacques Vandier, Manual of Egyptian archaeology: The great eras: Statuary, 3. Paris, 174, 215, 358; pl. 59, 1958

Cyril Aldred, Some Royal Portraits of the Middle Kingdom in Ancient Egypt, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 3, 1970

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Royal_Portraits_of_the_Middle_Kingdom_in_Ancient_Egypt_The_Metropolitan_Museum_Journal_v_3_1970

Christine Lilyquist, Peter F. Dorman, Edna R. Russmann, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 41, no. 3 (Winter), 1983

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Egyptian_Art_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art_Bulletin_v_41_no_3_Winter_1983_1984?Tag=&title=&author=&pt=%7B05598FA1-8F02-4579-A088-9F7BC7165316%7D&tc=&dept =

Mohamed Saleh, Hourig Sourouzian, Official catalog of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Verlag Philippe von Zabern, 1997

Francesco Tiradritti, Treasures of Egypt - The wonders of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Gründ, 1999

Isabelle Franco, Dictionary of Egyptian mythology, Pygmalion 1999

IFAO, el-Licht: Capital and royal residence of ancient Egypt

https://www.ifao.egnet.net/recherche/activites-passees/axes2012/espaces-pouvoir/2012-lisht/