Ancient Mesopotamian bricks record 3,000-year-old geomagnetic anomaly

A geomagnetic anomaly that occurred between 3,000 and 2,500 years ago has shed light on ancient Mesopotamia in a way that has never been explored before. Analysis of ancient bricks from Mesopotamia, specifically modern-day Iraq, indicates a significant rise in the Earth's magnetic field about 3,000 years ago. They are now the subject of a fascinating new study, which relies on archaeomagnetic techniques - extracting information about the strength and direction of the Earth's magnetic field from ancient objects - and offers an alternative way of dating artefacts.

Heating and cooling: brick firing

These ancient bricks from Mesopotamia, which contain iron oxide, were used to study the strength of the Earth's magnetic field during the launch period. Scientists systematically erased the ancient magnetic signature from small brick fragments through a heating and cooling process, according to the study published in The Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences.

The bricks were then reheated, and the original magnetic field was replaced by a field generated in the laboratory. This process enabled researchers to determine a ratio between an object's magnetic charge in the past and under controlled laboratory conditions.

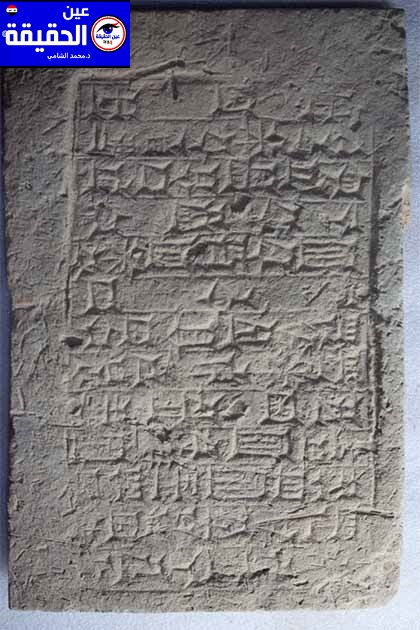

The bricks date to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (ca. 604 to 562 BC) based on the interpretation of the inscription. This piece was looted from its original context before the Sulaymaniyah Museum acquired it and stored it in that museum with the approval of the central government. (Photo from Sulaymaniyah Museum)

The bricks date to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (ca. 604 to 562 BC) based on the interpretation of the inscription. This piece was looted from its original context before the Sulaymaniyah Museum acquired it and stored it in that museum with the approval of the central government. (Photo from Sulaymaniyah Museum)

Professor Mark Tawil from University College London studies the exceptional strength of the magnetic field in the Middle East around 3,000 years ago, known as the Levantine Iron Age Geomagnetic Anomaly: : A point of high magnetic intensity between 1050-550 BC in modern-day Iraq. .

“We often rely on dating methods such as radiocarbon dating to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia. However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, cannot be easily dated because they do not contain organic materials.” ..

The results revealed that these bricks were burned at a time when the Earth's magnetic field was one and a half times stronger than its current intensity. This time period corresponds to the Iron Age geomagnetic anomaly in the Levant

This anomaly was initially identified in 2009 by members of the same research team in a nearby area, and investigated using similar methods but on layers of rocky material. History was literally baked into the bricks of cities during Iron Age Babylon, The Hill reports.

Another piece of clay brick from Mesopotamia, bearing the names of 12 kings, helped determine the chronology. (MIT license)

Al-Tawil and his colleagues identified a group of 32 clay bricks from Mesopotamia, each bearing inscriptions with the names of 12 different kings. It is assumed that these inscriptions were associated with the rulers during the period of brick making. What makes these bricks particularly valuable for scientific analysis is the presence of iron oxide grains within them.

These granules have the unique ability to maintain the direction and strength of the magnetic field that was present when the bricks were initially fired. By examining the inscriptions and measuring the magnetic properties of the iron oxide grains, the researchers obtained insightful information about the Earth’s magnetic field during the periods of the rule of the kings.

Source: MIT license