Carthage was a Phoenician city-state on the coast of North Africa (the site of modern-day Tunis) which, prior the conflict with Rome known as the Punic Wars (264-146 BCE), was the largest, most affluent, and powerful political entity in the Mediterranean. The city was originally known as Kart-hadasht (new city) to distinguish it from the older Phoenician city of Utica nearby. The Greeks called the city Karchedon and the Romans turned this name into Carthago.

Roman Naval Attack on Carthage

It was founded c. 814 BCE by the legendary Phoenician queen Dido, increased in size after an influx of refugees from the city of Tyre following Alexander the Great's conquests of 332 BCE, and afterwards expanded until it was the seat of the Carthaginian Empire with colonies (such as Sabratha) along the North African coast, in Sicily, Spain, and elsewhere; these would all be lost following the Punic Wars which elevated Rome to Carthage's former position as the greatest Mediterranean power.

The history of the ancient city is usually divided into five periods:

Ancient Carthage (Punic Republic) – c. 814-146 BCE

Roman Carthage – 146 BCE - 439 CE

Vandal Carthage – 439-534 CE

Byzantine Carthage (Exarchate of Africa) – 534-698 CE

Muslim Arab Carthage (Islamic Carthage) – 698-1270 CE

Owing to limitations of space, this article will primarily deal with Ancient Carthage/the Punic Republic.

In 698 CE, the city was conquered during the Muslim Arab invasion of North Africa and destroyed. It would be rebuilt, though on a modest scale compared with the city at its height, until it was completely destroyed under the reign of Muhammad I al-Mustansir (r. 1228-1277 CE) after defeating the European Christian invasion of the Eighth Crusade of 1270 CE. The site would continue to be inhabited, though the ancient ruins were neglected until the 1830s CE when modern excavations began.

Foundation & Expansion

According to legend, Carthage was founded by the Phoenician Queen Elissa (better known as Dido) c. 814 BCE; although Dido's historicity has been challenged, the founding does date to about this time. Dido was allegedly fleeing the tyranny of her brother Pygmalion of Lebanon, landed on the coast of North Africa, and established the city on the high hill later known as the Byrsa. The legend claims that the Berber chieftain who controlled the region told her she could have as much land as an ox hide would cover; Dido cut a single ox hide into thin strips and lay them end-to-end around the hill, successfully claiming it for her people.

THE CITY DEVELOPED SIGNIFICANTLY FOLLOWING ALEXANDER'S DESTRUCTION OF THE GREAT INDUSTRIAL & TRADE CENTER OF TYRE WHEN REFUGEES FLED TO CARTHAGE.

Dido's reign is described by the Roman poet Virgil (l. 70-19 BCE), and others, as impressive, noting how the city grew from the small community on the hill to a grand metropolis. This account, and others like it, are legendary but Carthage, which seems to initially have been a minor port on the coast where Phoenician traders stopped to resupply or repair their ships, was clearly a major center of trade by the 4th century BCE.

The city developed significantly following Alexander's destruction of the great industrial and trade center of Tyre (considered Carthage's mother-city) in 332 BCE when Phoenician refugees fled from there to Carthage. These Tyrians arrived with whatever wealth they had and, since many whom Alexander spared were those rich enough to buy their lives, they landed in the city with considerable means which established Carthage as the new center of Phoenician trade.

The Carthaginians then established a working relationship with the tribes known as the Masaesyli and the Massylii of the North African Berber (Imazighen) Kingdom of Numidia who would fill the ranks of their military, primarily as formidable cavalry troops. From a small town on the coast, the city grew in size and grandeur with enormous estates covering miles of acreage. Carthage quickly became the richest and most powerful city in the Mediterranean.

Carthaginian government, formerly a monarchy, was a republic based on meritocracy (rule of the elite) by the 4th century BCE. The top position was held by two elected magistrates known as suffetes (“judges”) who governed in conjunction with a senate of between 200-300 members who held the position for life. Laws were passed by an assembly of citizens who would vote on measures proposed by the suffetes and senate. The aristocrats lived in palaces, the less affluent in modest but attractive homes, and the lower classes in apartments or huts outside the city.

Tribute and tariffs regularly increased the city's wealth on top of the lucrative business in maritime trade. The city's harbors were immense, with 220 docks, and gleaming columns which rose around it in a half-circle, in front of towering arches and buildings ornamented with Greek sculpture. There were two harbors, one for trade and the other for warships, which operated constantly in resupplying, repairing, and outfitting vessels. The Carthaginian trading ships sailed daily to ports all around the Mediterranean Sea while their navy, supreme in the region, kept them safe and, also, opened new territories for trade and resources through conquest as the Carthaginians built their empire.

Carthage and its Harbour

The city had four residential sections, which grew up around the citadel of the Byrsa in the center, and was surrounded by walls which stretched 23 miles (37 kilometers) in length from the harbors inland. The city had all the accommodations and refinements of any great ancient city – a theater for entertainment, temples for religious observances, a necropolis, an agora (marketplace) – but on a much grander scale. Its patron deity was the goddess of love and fertility, Tanit who was worshipped alongside her consort Baal-Hamon. It is possible that children were sacrificed to Tanit in the sacred precinct known as the Tophet, but this claim has been challenged, and it is equally likely that the Tophet of Carthage was simply a necropolis reserved for infants and the young.

Affluence & Invasion

The city's wealth was due not only to its advantageous position on the North African coast, from which it could control sea traffic between itself and its colony on Sicily, but also to the people's skill in agriculture. The writer Mago of Carthage (dates unknown) wrote a work of 28 volumes devoted to agriculture and veterinarian science which was considered the most comprehensive on the subject of its time and reflects the Carthaginian's intense interest in farming and animal husbandry. Mago's works were considered so important that they were among the few that would be spared by the Romans after Carthage's final defeat in 146 BCE. Roman references to the books are now all that remain of them.

The Carthaginians planted fruit trees, grapes, olive trees, and vegetables in a ring of gardens irrigated by small canals and then expanded their cultivation outward beyond the city walls to fields of grains. The fertility of the land, and their expertise in cultivation, increased the city's wealth through trade with the interior as well as maritime trade elsewhere as Carthage continued to flourish.

Seasons Mosaic, Carthage

It was this expansion that first brought Carthage into conflict with others. In 310-307 BCE, North Africa was invaded by Agathocles of Syracuse (r. 317-289 BCE) who sought to subdue Carthage and use her wealth to fund his wars. Agathocles was able to feed his army easily off the land because the crops grew in such abundance. He was only defeated because the Libyans and Berbers, who worked the land, sided with the Carthaginians who had treated them well. Agathocles was driven from North Africa and Carthage continued to prosper until it became involved in a conflict with Rome, then just a small city-state on the Tiber River in Italy, in 264 BCE.

The Punic Wars

Control of Sicily was divided between Rome and Carthage who supported opposing factions on the island which quickly brought both parties into conflict directly with each other. These conflicts would be known as the Punic Wars from the Phoenician word for the citizens of Carthage (given in Greek as Phoinix and in Latin as Punicus). When Rome was weaker than Carthage, they posed no threat. The Carthaginian navy had long been able to enforce the treaty which kept the Roman Republic from trading in the western Mediterranean. When the First Punic War (264-241 BCE) began, however, Rome proved far more resourceful than Carthage could have imagined.

Though they had no navy and knew nothing of fighting on the sea, Rome quickly built 330 ships which they equipped with clever ramps and gangways (the corvus) which could be lowered onto an enemy ship and secured; thus turning a sea battle into a land battle. After an initial struggle with military tactics, Rome won a series of victories and finally defeated Carthage in 241 BCE. Carthage was forced to cede Sicily to Rome and pay a heavy war indemnity.

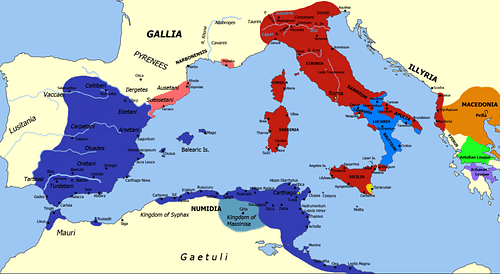

Territories During the Second Punic War

Following this war, Carthage became embroiled in what is known as The Mercenary War (241-237 BCE) which started when the Carthaginian army of mercenaries demanded the payment Carthage owed them. This war was finally won by Carthage through the efforts of the general Hamilcar Barca (l. c. 285 - c. 228 BCE), father of the famous Hannibal Barca (l. 247-183 BCE) of the Second Punic War.

Carthage suffered greatly from the First Punic and Mercenary War and, when Rome occupied the Carthaginian colonies of Sardinia and Corsica, there was nothing the Carthaginians could do about it. They tried to make the best of their situation by expanding holdings in Spain but again went to war with Rome when Hannibal attacked the city of Saguntum, an ally of Rome in Spain, in 218 BCE.

The Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) was fought largely in northern Italy as Hannibal invaded Italy from Spain by marching his forces over the Alps. Hannibal won every engagement against the Romans in Italy. In 216 BCE he won his greatest victory at the Battle of Cannae but, lacking sufficient troops and supplies, could not build on his successes. He was finally drawn from Italy and defeated by the Roman general Scipio Africanus (l. 236-183 BCE) at the Battle of Zama, in North Africa, in 202 BCE and Carthage again sued for peace.

Placed, again, under a heavy war indemnity by Rome, Carthage struggled to pay their debt while also trying to fend off incursions from neighboring Numidia under the king Masinissa (r. c. 202-148 BCE). Masinissa had been Rome's ally in the Second Punic War and was encouraged by Rome to raid Carthaginian territory at will. Carthage went to war against Numidia and, in so doing, broke the peace treaty with Rome which forbid Carthage from mobilizing an army.

Carthage felt it had no choice but to defend itself against Masinissa's invasions but was censured by Rome and ordered to pay a new war debt to Numidia. Having only recently paid off their debt to Rome, they now owed a new crippling war debt. Rome was not concerned with whatever conflict Carthage and Numidia were involved in but did not care for the sudden revitalization of the Carthaginian military.

Punic Cuirass

Carthage believed that their treaty with Rome was ended when their war debt was paid; Rome disagreed. The Romans felt that Carthage was still obliged to bend to Roman will; so much so that the Roman Senator Cato the Elder ended all of his speeches, no matter what the subject, with the phrase, “Further, I think that Carthage must be destroyed.” In 149 BCE, Rome decided upon just that course of action.

A Roman embassy to Carthage presented a list of demands which included the stipulation that Carthage be dismantled and then rebuilt further inland, thus negating the long-recognized advantage it had in trade from its position on the coast. The Carthaginians, understandably, refused to do so and the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE) began.

The Roman general Scipio Aemilianus (l. 185-129 BCE) besieged Carthage for three years until it fell. After sacking the city, the Romans burned it to the ground, leaving not one stone on top of another. A modern myth has grown up that the Roman forces then sowed the ruins with salt so nothing would ever grow there again but this claim has no basis in fact. It is said that Scipio Aemilianus wept when he ordered the destruction of the city and behaved virtuously toward the survivors of the siege.

Later History

POWER SHIFTED FROM UTICA BACK TO CARTHAGE & IT REMAINED AN IMPORTANT ROMAN COLONY UNTIL IT FELL TO THE VANDALS.

Utica now became the capital of Rome's African provinces and Carthage lay in ruin until 122 BCE when Gaius Sempronius Gracchus (l. 154-121 BCE) the Roman tribune, founded a small colony there. Gaius' political problems, and the memory of the Punic wars still being too fresh, however, caused the colony to fail. Julius Caesar proposed and planned the rebuilding of Carthage and, five years after his death, Carthage rose again. Power now shifted from Utica back to Carthage – which became Rome's breadbasket owing to the same agricultural success which had enriched it before - and it remained an important Roman colony until it fell to the Vandals under their king Gaiseric (r. 428-478 CE) in 439 CE.

Carthage had risen in prominence as Christianity grew and Augustine of Hippo (St. Augustine, l. 354-430 CE) contributed to its prestige by living and teaching there. The city was considered so illustrious, in fact, that the Council of Carthage of 397 CE was held there; the series of synods which would confirm the biblical canon for the Western Church, legitimizing the narratives which would come to be known as the Bible. The Vandal invasion of North Africa did nothing to halt Christianity's development there, but tensions would rise between the Arian Christians (the Vandals primarily) and Trinitarian Christians just as they did elsewhere.

The Vandals under Gaiseric took full advantage of the location of their new city and plundered passing ships at will while also raiding coastal cities. Roman attempts to dislodge them failed and so a treaty was signed in 442 CE between Gaiseric and Valentinian III (r. 425-455 CE) acknowledging the Vandal Kingdom of North Africa as a legitimate political entity and establishing peaceful relations. When Valentinian III was assassinated in 455 CE, however, Gaiseric disregarded the treaty, believing it was an agreement only between himself and the emperor, and sailed for Rome. He looted the city but, in accordance with the request of Pope Leo I (served 440-461 CE), did not damage it nor harm the populace. The Vandals would continue to hold Carthage, and profit from its location, until after Gaiseric's death.

Coin of King Gelimer

The later Vandal king Gelimer (r. 530-534 CE), an Arian Christian, reinstituted the persecution of Trinitarian Christians which enraged the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE), a trinitarian, who sent his great general Belisarius (l. 505-565 CE) to North Africa. Belisarius won the short-lived Vandalic War (533-534 CE), brought Gelimer back to Constantinople in chains, and restored Carthage to the Byzantine Empire (330-1453 CE) under which it continued to flourish.

Under the Byzantines, Carthage prospered through trade and as a major source of grain for the Eastern Roman Empire (the Western Roman Empire having fallen c. 476 CE). Around 585 CE, Carthage became the seat of the Exarchate of Africa under the Byzantine emperor Maurice (r. 582-602 CE), a separate administrative region established for more effective rule of the western areas of the empire.

In 698 CE, the Muslims defeated the Byzantine forces at the Battle of Carthage, destroyed the city completely, and drove the Byzantines from Africa. They then fortified and developed the neighboring city of Tunis and established it as the new center for trade and governorship of the region. Under the Arab Muslims, Tunis fared better than Carthage, but the city continued to thrive until the Eighth Crusade of 1270 CE when it was taken by the European Crusaders who fortified the citadel of the Byrsa. Once they were defeated, Muhammad I al-Mustansir had the city's defenses torn down and many of the buildings razed to prevent any further such occupation.

Conclusion

The site of the ancient city continued to be inhabited and was included in the region taken by the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922 CE) who had no interest in excavating the ruins. The stones of the fallen houses, temples, and walls were carried off for personal or administrative building projects or left where they had been found. Modern archaeological excavation began in the 1830s CE through the efforts of the Danish consulate and continued under the French between c. 1860-1900 CE.

Further work at the site was undertaken throughout the first part of the 20th century CE but, as at Sabratha and other sites, the archaeologists were more interested in the Roman history of Carthage. The political and cultural zeitgeist of the time defined the Carthaginians, who were Semites, as a people of little value, and anti-Semitism significantly influenced not only the interpretation of physical evidence but the choice of what was kept for placement in museums or discarded.

The history of the period of Ancient Carthage, therefore, suffered as much from these modern-day excavations as from the city's destruction by Rome or later conflicts. It was not until after World War II that systematic, unbiased, work at Carthage would begin; a paradigm consistent with the excavation and interpretation of many other ancient sites.

Carthage still lies in ruin in modern-day Tunisia and remains an important tourist attraction and archaeological site. The outline of the great harbor can still be seen as well as the ruins of the homes, public baths, temples, and palaces from the time when the city of Carthage ruled the Mediterranean as the most opulent jewel of the North African coast.

Bibliography

Adkins, L & Adkins, R. A. Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Appian. Roman History. Harvard University Press, 1913.

Durant, W. Caesar and Christ. Simon & Schuster, 1980.

Grant, M. Readings in the Classical Historians. Scribner, 1993.

Lewis, J. E. The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Ancient Rome. Running Press, 2003.

Matyszak, P. The Enemies of Rome: From Hannibal to Attila the Hun. Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Mellor, R. The Historians of Ancient Rome. Routledge, 2012.

Miles, R. Carthage Must Be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Civilization. Penguin Books, 2012.

Nardo, D. Living in Ancient Rome. Thompson/Gale Publishers, 2004.

Warmington, B. H. Carthage: A History. Barnes & Noble Inc, 1999.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language! So far, we have translated it to: Spanish, Italian, Russian

About the Author

Joshua J. Mark

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

https://www.worldhistory.org/carthage/