The Gold Trade of Ancient & Medieval West Africa

West Africa was one of the world's greatest producers of gold in the Middle Ages. Trade in the metal went back to antiquity but when the camel caravans of the Sahara linked North Africa to the savannah interior, the trade really took off. A succession of great African empires rose off the back of the gold trade as salt, ivory, and slaves were just some of the commodities exchanged for the precious metal that eventually found its way into most of southern Europe's gold coinage. Gold attracted unwanted attention and competition, too, with the Portuguese the first to exploit West Africa's coastal resources from the 15th century CE, and in their wake followed others. The discovery of the Americas and the gold of the Aztecs and Incas only gave West Africa a temporary respite as European colonial powers then returned to the continent as their chief source of slaves to work on the plantations of the New World.

Almoravid Gold Coin

West African Gold in Antiquity

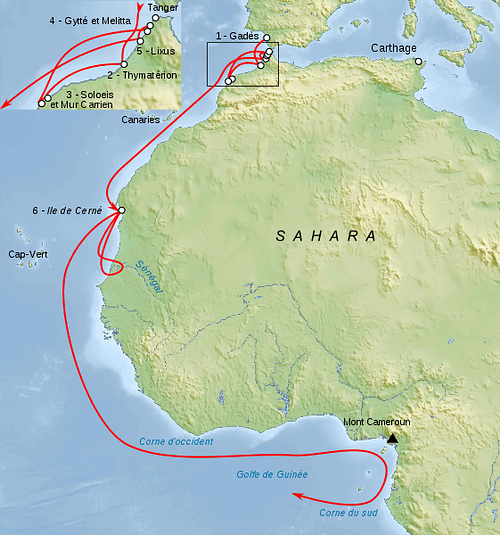

The trade of gold in West Africa goes back to antiquity with one of the earliest examples being the voyage of the Carthaginian explorer Hanno in the 5th century BCE. The celebrated mariner sailed out of the Mediterranean and, turning south, stopped off at the mouth of the Senegal River before sailing on and perhaps even reaching as far the Bay of Guinea. Hanno was followed by other countrymen, and commercial relations were established with the locals. Thus, West African gold found its way from the trading post/island of Cerne (unidentified but on the Atlantic coast) northwards to the ancient Mediterranean cultures for the first time.

The 5th-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus describes in his Histories that gold was traded on the West African coast using a silent and cautious method of barter - perhaps understandable given the language barrier and mutual fear between unfamiliar peoples:

The Carthaginians tell of a place in Libya outside the Pillars of Hercules [Straits of Gibraltar] inhabited by people to whom they bring their cargoes. The Carthaginians unload their wares and arrange them on the beach; then they reboard their boats and light a smoky fire. When the native inhabitants see the smoke, they come to the shore and, after setting out gold in exchange for the goods, they withdraw. The Carthaginians disembark and examine what the natives have left there, and if the gold appears to them a worthy price for their wares, they take it and depart; if not, they get back on their boats and sit down to wait while the natives approach again and set out more gold, until they satisfy the Carthaginians that the amount is sufficient. (Book 4. 197)

Voyage of Hanno the Carthaginian Explorer

The Romans were also interested in what Africa's interior had to offer and they employed cross-Saharan traders to exchange olive oil, fine pottery and luxury goods for commodities such as gold, ivory, ebony and exotic animals for shows in the amphitheatres and circuses. Roman Tripolitania in modern-day Libya, became a particularly successful trading city on this basis. However, it would not be until the 8th century CE and the twin arrival of the North African Islam caliphates and the hardy camel that trans-Saharan trade really took off and with it the boom in the gold trade.

Medieval West Africa

The Islamic North African empires of the medieval period had an insatiable demand for gold because it was needed not only for making precious manufactured goods (e.g. jewellery, vessels, embroidered clothing and illuminated manuscripts) but also to mint coinage to pay armies. Traditional Islamic teachings might have forbidden men to wear gold but a few coins in one's pocket was especially useful for soldiers of no fixed abode. The Islamic sensitivity to the metal is also evidenced by the fact that jewellery work was most often done by Jewish craftsmen once it reached the North African cities. In addition, gold was needed to pay the growing number of Spanish, Italian, and other European merchants who traded in the southern Mediterranean. Much of that gold then ended up as coinage in such places as Castille, Genoa, Florence, and Venice from the late 13th century CE.

THE GHANA EMPIRE BECAME FAMOUS FOR ITS GOLD, EARNING ITSELF THE NICKNAME THE 'LAND OF GOLD.'

The great problem for the North African states was that to obtain the gold of West Africa they had to first cross the Sahara desert and then deal with the African rulers who monopolised the gold trade. Consequently, camel caravans controlled by Sanhaja Berbers and the Tuareg came into their own as a means to cross the dangerous and inhospitable Sahara and acquire the precious metal from Africa's interior and bring it back to such cities as Marrakesh, Fez, Tunis, and Cairo. This they did with great success and, at the trade's peak, two-thirds of the gold moving around the medieval Mediterranean came from West Africa.

The Ghana Empire - 'Land of Gold'

One of the first sub-Saharan states in West Africa to gain attention in the wider medieval world was the Ghana Empire (6-13th century CE), located in modern-day southern Mauritania and Mali. The empire became famous for its gold, earning itself the nickname the 'land of gold.' The metal came from goldfields in Ghiyaru, Galam, and Bure on the upper Niger River (modern Guinea), and via traders who brought it from the goldfields of Bambuk at the meeting of the Falem and Senegal Rivers. Gold was largely found in alluvial deposits where it was easily panned to find gold dust and grains or in veins in relatively shallow mines. Mine shafts were typically only a few metres deep and produced a mere 2.5 to 5 grammes of gold each so thousands of shafts were dug in a single gold-bearing area. Most gold was not refined - although its purity was high anyway - but was melted down to cast it into convenient bars for transportation.

Camel Caravan, Morocco

The most common commodity that gold was used to purchase was salt, a mineral that was always in great demand in order to better preserve dried meat and to give added taste to food. The Savannah region south of the western Sahara desert (known as the Sudan region) and the forests of southern West Africa were poor in salt. Camel caravans brought great slabs of rock salt to the south across the Sahara from such natural deposits as found at Idjil, Awlil, and Taghaza, and took gold back in the other direction as well as other valuable goods like ivory and slaves. Certain towns grew rich on the gold-salt trade. In the 11th century CE, a 90-kilo block of salt, transported by river from Timbuktu to Djenne (aka Jenne) in the south could double its value and be worth around 450 grams of gold. By the time the salt was passed on down to the southern forests of lower West Africa, the mineral could be literally worth its weight in gold.

ANY NUGGET WHICH WEIGHED BETWEEN 25 GRAMMES & HALF A KILO (1 OZ TO 1 LB) BECAME THE PROPERTY OF THE GHANA KINGS.

Although there is no evidence that, unlike salt and copper, the trade or passage of gold was taxed in the Kingdom of Ghana, the commodity was very carefully controlled by the Ghana kings. Any nugget which weighed between 25 grammes and half a kilo (1 oz to 1 lb) became the property of the king who kept a great stockpile in his palace complex. Rather than an example of sheer avarice, this strategy was likely employed in order not to flood the market and so maintain the value of gold dust. Sizeable chunks of the metal had an association with magic which was another reason for the king to keep them as he was regarded as the supreme magician of the indigenous African religion before Islam came along (and sometimes even after it). One Arab writer, Muhammad al-Idrisi (1100-1165 CE), noted that one king had amongst his collection a single block of gold weighing over 13.5 kilos (30 pounds).

This royal monopoly of nuggets meant that the vast majority of gold which exchanged hands between traders and ordinary people in the Ghana kingdom was in the form of gold dust. This golden powder was carefully measured out, typically using small scales and glass weights. Gold dust and sometimes wire were used as a currency in some states but only rarely, and there is no archaeological evidence that sub-Saharan states ever minted their own gold coinage. Rather, the most common purpose of gold was for barter for imported goods. The other use was for decoration and could be seen in all manner of objects, especially, of course, those used by royalty such as regalia, shields, swords, jewellery, clothing, and even dog chains and collars.

The Mali Empire - The Riches of Mansa Musa

The Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE) gained access to new goldfields on the Black Volta (modern-day Burkina Faso) and in the Akan Forest (modern-day Ghana), and its kings became even wealthier than their regional predecessors in the Ghana Empire. Mali probably did not directly control the southern gold-bearing regions but, rather, extracted from them the precious metal as tribute.

Map of the Mali Empire, c. 1337 CE

Mali's most famous ruler was Mansa Musa I (1312-1337 CE). Having converted to Islam, Mansa Musa duly went off on a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 CE. When he stopped off at Cairo en route in July of that year, the king's wealth in gold caused an absolute sensation. In some accounts, Mansa Musa's caravan included 100 camels which carried 135 kilos (300 pounds) of gold dust while 500 slaves each brandished a 2.7 kilo (6 pounds) gold staff. After straight away giving 50,000 gold dinars to the sultan of Egypt merely as a gesture of goodwill between two great rulers, Mansa Musa would subsequently give away so much gold and his entourage spend so much of it shopping in the markets of the city that the value of the gold dinar in Cairo crashed by 20% (in relation to the silver dirham); it would take 12 years for the flooded gold market to recover.

Although Mansa Musa kept the exact source of his gold a closely-guarded secret, news spread far and wide that this exotic ruler was perhaps the richest man in the world. Even in Spain, a mapmaker was inspired to create Europe's first detailed map of West Africa c. 1375 CE, and on it, Mansa Musa is depicted wearing a golden crown and holding a gold staff and nugget in each hand. The consequent stories of a city paved in gold somewhere in the heart of Africa, the fabled Timbuktu, would tantalise many an explorer and adventurer for the next four centuries.

The Songhai Empire & Its Rivals

The Mali Empire's successor as the most powerful state in West Africa was the Songhai Empire (c. 1460 - c. 1591 CE). The Songhai, continuing the tried-and-tested wealth accumulation method of trading sub-Saharan commodities and extracting tribute from conquered tribes, established the largest and richest empire yet seen in West Africa. However, things took a turn for the worse in 1471 CE when a Portuguese fleet, sponsored by the Lisbon merchant Fernão Gomes, sailed around the Atlantic coast of Africa and established a trading presence near the gold fields of southern West Africa. In addition, other kingdoms arose to compete with the Songhai for a share of the gold trade, especially to the west the Bornu Empire (1396-1893 CE) near Lake Chad, Hausaland (c. 1400 - c. 1800 CE) between the Niger River and Lake Chad, and, in the south, the Kingdom of Benin (13-19th century CE) in modern-day Nigeria.

Mansa Musa of the Mali Empire

The Portuguese in West Africa

The Portuguese ships which now regularly sailed down the Atlantic coast of Africa offered West African forest peoples a middle-man-free alternative to the trans-Saharan caravan routes. The Portuguese were especially keen to obtain gold because they needed it to pay merchants in Asia who were not so keen on exchanging goods in kind. There was still, though, plenty of gold travelling northwards through the Songhai Empire and onto North Africa but the African monopoly of the trade was now at an end.

In the 15th century CE, West Africa was producing 10% of the world's gold. On average, some 400-550 kilos a year were being handled by the Portuguese alone in the 1500s CE. Not surprisingly, European powers began to show an interest, such as England, France, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Fortifications were built, not to defend the Europeans from the native Africans but from each other. In short, it seemed that West Africa had exactly what everyone else most wanted: slaves and gold.

Later History

West African gold continued to be exploited after the medieval period as European powers competed for whatever they considered of value in the continent. The gold extracted from West Africa, though, was dwarfed by that extracted from the New World, the Inca civilization and Aztec civilization, in particular. European powers were also now far more interested in acquiring slaves than gold, many of them destined to work in the plantations of the Americas.

West Africa was not finished with gold, though, and kept producing it using much the same simple methods as had always been employed. The modern state of Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast, gained independence from Britain in 1961 CE, and the introduction of new mining technology meant that it once more played a major role in the international gold markets. For a while, Ghana ranked 5th in the world in terms of annual gold production. Already in the mid-19th century CE, though, attention had turned elsewhere for new sources of the precious metal. Australia became a major source of gold from 1851 CE, and from 1898 CE South Africa became the world's biggest producer of gold, a position only relatively recently challenged and overtaken by China, Russia, the United States, Canada, and Peru.

Bibliography

Bagnall, R. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012

Curtin, P. African History. Pearson, 1995.

de Villiers, M. Timbuktu. Walker Books, 2007.

Fage, J.D. (ed). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Green, T. The Gold Companion. Rosendale Press Ltd, 1992.

Hornblower, S. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Hrbek, I. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. III, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1992.

Ki-Zerbo, J. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1998.

McEvedy, C. The Penguin Atlas of African History. Penguin Books, 1996.

Oliver, R. (ed). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Oliver, R.A. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa. Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Strassler, R.B. The Landmark Herodotus. Anchor Books, 2009.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language! So far, we have translated it to: Portuguese, French

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1383/the-gold-trade-of-ancient--medieval-west-africa/