The Price of Greed: Hannibal's Betrayal by Carthage

Hannibal Barca (l. 247-183 BCE), the brilliant Carthaginian general of the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE), had the military talent, expertise, and skill to have won the conflict but was denied the resources by his government. The Carthaginian senate repeatedly refused Hannibal's requests for aid and supplies even as they were relying on him to win the war for them.

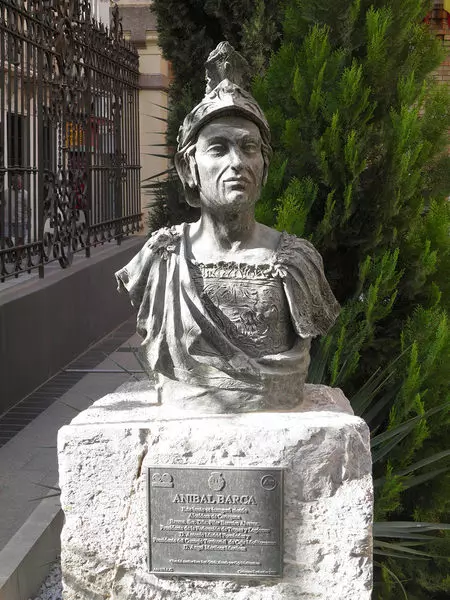

Hannibal Barca Bust

This kind of selfish behavior should have come as no surprise to the general since the Carthaginian government had responded in the same way to his father, Hamilcar Barca (l. 275-228 BCE) during the First Punic War (264-241 BCE). Hamilcar had also repeatedly sent word that he required greater support and these pleas were ignored by the elite of the city who preferred to spend the peoples' tax money on their own luxuries instead of the good of the populace who supported their way of life.

Hannibal continued to fight for the people of Carthage, in spite of the poor treatment he received, throughout the Second Punic War and yet never received the gratitude he was owed. Even after he was defeated by Scipio Africanus (l. 236-183 BCE) at Zama in 202 BCE, he continued to serve Carthage as best he could, acting as the magistrate who oversaw payment of the war indemnity to Rome, and even then he was accused of impropriety and denounced by the elite who valued their own comfort and luxury over the good of the people.

Background & Situation

THE CARTHAGINIAN SENATE CONTINUALLY REFUSED AID & REINFORCEMENTS TO HANNIBAL.

Hannibal's forces were defeated on the field at the Battle of Zama by Scipio's brilliant manipulation of the Carthaginian's own tactics but the groundwork for this defeat was laid throughout the Second Punic War through the Carthaginian government's refusal to support their general and his troops on campaign in Italy. As they had done with Hamilcar Barca in the First Punic War, the Carthaginian senate continually refused aid and reinforcements to Hannibal in the hope that he would somehow defeat Rome without them having to inconvenience themselves too much by funding his campaigns.

This policy was nothing new for the Carthaginian aristocracy. They had followed this same course earlier, notably in their war with Agathocles the tyrant of Syracuse (r. 317-289 BCE). Generals were expected to deal with threats to the state but were not given the kind of support they actually needed to win. This was not only because the elite did not wish to spend the money, but because the aristocracy feared that the commander they funded might then become too powerful. Scholar Richard Miles comments:

Although these generals were drawn from Carthaginian ranks, they had been chosen not by [the senate] but by the whole citizenry of Carthage in the Popular Assembly. This fact alone placed them under suspicion by the elite…The ports of Sicily [where generals developed their army against Agathocles] were hundreds of kilometers away from Carthage, and news of events on the island was sporadic and often inaccurate. In such circumstances, it was easy for a military commander to forget that he was answerable to his peers. (146-147)

The senate, therefore, sought to undercut a commander's ability to perform the very task they had assigned, thereby keeping him dependent on their goodwill. At the same time, they expected a general to win for them, as noted by the historian Timaeus who writes, “In their wars, they advance their leading men to commands, taking it for granted that these should be the first to brave the danger for the whole state” (Miles, 147). They were unwilling, however, to give these commanders the resources to actually achieve the victories they demanded.

Rome had never known an adversary like Hannibal, who struck in their own backyard, and, after the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE, Hannibal was in a position of power to crush Rome completely. He had the brilliant strategies of Carthaginian warfare and the momentum of victory, but he did not have the resources.

Hannibal Comes to Power

According to the Greek historian Polybius, Hannibal's father made his son swear an oath of enmity towards Rome for life. Hannibal allegedly took this oath and, throughout his campaigns against the Romans, made good on it (Polybius' Histories, 3:11). After the First Punic War, Carthage was burdened by a large indemnity it was expected to pay Rome. Hamilcar went to Spain, ostensibly, to raise money from the Carthaginian-held silver mines but actually to mobilize a new army to continue the war with Rome. He took his son-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair (l. c. 270-221 BCE) with him as well as Hannibal, then only nine years old, and would later send for Hannibal's younger brother Hasdrubal Barca (l. c. 244-207 BCE). The scholar Philip Matyszak notes:

The modern concept of teenagers as somewhere between child and adult did not exist in the ancient world, and Hannibal was given charge of troops at an early age. (23)

When Hamilcar died in 228 BCE, command went to Hasdrubal the Fair who favored diplomatic measures in dealing with Rome. He negotiated the Ebro Treaty in 226 BCE which stipulated the Ebro River as the boundary between Carthaginian and Roman territories in Spain and established the agreement that neither party would interfere with the other one's business.

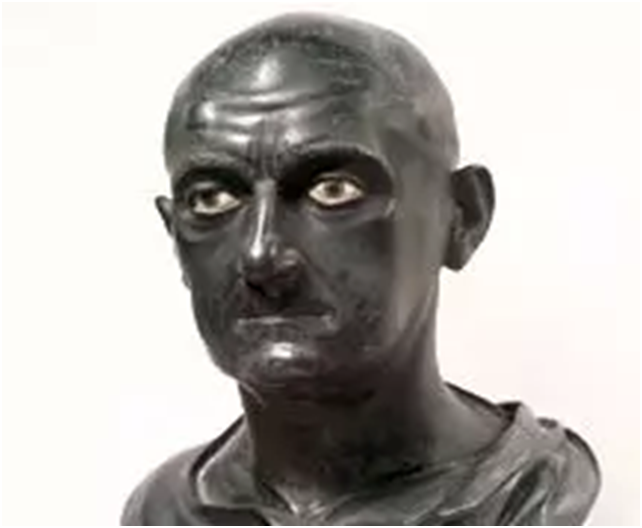

Hamilcar Barca

Hasdrubal was assassinated in 221 BCE and the Carthaginian army elected Hannibal as their commander. In 219 BCE, Rome supported a coup in the city of Saguntum – in Carthaginian territory – and in 218 BCE Hannibal marched on the city and took it. The Romans demanded Carthage surrender the general to them, Carthage refused, and the Second Punic War began. The Romans had subdued the Gauls of Spain who saw them as conquerors and occupiers, and so when Hannibal began his operations in Iberia, they did little to stop him and, in fact, encouraged his efforts.

Hannibal & His Campaigns

Hannibal not only had the support of the people but, equally important if not more so, the devotion of his army. Only 25 years old upon assuming command, Hannibal had spent most of his life in army camps on campaign. The historian Will Durant, quoting Livy, writes, “He was the first to enter the battle and the last to abandon the field” (48). Hannibal's army knew they could depend on him to take care of them just as surely as they knew the punishments awaiting them if they disappointed him. In this same way, the people of the region looked to Hannibal to relieve them of the Romans. With a general like this in command of the troops, Carthage had only to keep him well supplied and equipped to conquer all of Spain and continue on into Italy to crush Rome.

HANNIBAL'S ARMY GREW AS HE MARCHED BECAUSE HE CONSISTENTLY PORTRAYED HIMSELF AS A LIBERATOR TO THE CONQUERED PEOPLE OF THE REGION.

Unlike his father, who had to rely on mercenaries in the First Punic War, Hannibal swelled his ranks with Carthaginians, Gauls, Spaniards, and Libyans who hated Rome. In 218 BCE he crossed the Ebro into Roman territory with 50,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry. His army grew as he marched because he consistently portrayed himself as a liberator to the conquered people of the region. Hannibal was determined to bring the battle to Rome and so, famously, led his troops across the Alps into northern Italy. After 17 days in the mountains, Hannibal's forces, now greatly reduced by the hazardous march, descended onto the plains.

Though now numbering less than 26,000 total, Hannibal seized towns and marched south toward Rome, defeating a numerically superior Roman army at the Ticino River in 218 BCE. At Lake Trasimeme, Hannibal defeated another large force, under the command of Caius Flaminius, in 217 BCE, and stood in control of all of northern Italy. At this time, he sent word to Carthage asking for reinforcements and supplies; he was refused. The Carthaginian senate felt he would do better to have his army forage and live off the land.

As his forces were too small to take large-scale cities, and as he had lost many of his elephants in the Alps and had no siege engines, Hannibal's strategy was to lure the cities of Italy to his side through repeated victories and promoting himself as a liberator of the people. Hannibal won against every general Rome sent against him until finally they stopped sending anyone. The Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus (l. c. 280-203 BCE) thought it most prudent to refrain from battle and simply keep Hannibal pinned down while depriving him of food for his army through a scorched earth policy.

Hannibal's Major Battles in Italy

Fabius understood that Carthage was not resupplying their general and engaged Hannibal in a cat-and-mouse game in which Fabius hoped that the Carthaginian forces would succumb to disease and starvation. He was ridiculed and given the nickname “the delayer” for his reluctance to meet Hannibal in battle but Fabius recognized he was dealing with an unconventional adversary and so chose unusual means in trying to defeat him. He ignored the traditional Roman approach of fielding large numbers of men to crush an opponent in the hope of saving Roman lives. Scholar Ernle Bradford comments:

The one thing that Fabius had to do, he realized, was avoid defeat. The victory that he must aim for was not the traditional one upon the battlefield – something that the genius of his opponent rendered unlikely – but success achieved over a very long period of time, if need be. (95)

In 216 BCE, however, the Roman Senate, tired of inaction, elected Minucius Rufus (dates unknown) to command with Fabius. Fabius still held to his policy of caution while Rufus demanded action against the enemy. Fabius gave Rufus half the army which he then led against Hannibal near the town of Gerione and was swiftly defeated. Fabius had to rescue the younger general and surviving troops from a complete slaughter.

Hannibal Riding a War Elephant

Fabius then resigned and the armies were given to Lucius Aemilius Paulus (d. 216 BCE) and Caius Terentius Varro (served c. 218-200 BCE) who followed Rufus' policy of direct action. They met Hannibal on the field at the Battle of Cannae in August of 216 BCE and the Roman army was almost annihilated. By the end of battle, the Romans had lost 44,000 out of their approximately 80,000 men as opposed to Hannibal's losses of 6,000. Durant comments on the victory:

Hannibal placed the Gauls at his center, expecting that they would give way. They did; and when the Romans followed them into the pocket, the subtle Carthaginian, himself in the thick of the fray, ordered his veterans to close in upon the Roman flanks and bade his cavalry smash through the opposed horsemen to attack the legions from behind. The Roman army was surrounded…It was a supreme example of generalship, never bettered in history. It ended the days of Roman reliance upon infantry and set the lines of military tactics for two thousand years. (50-51)

General Paulus was killed in battle along with 80 senators who had enlisted as soldiers under him. Varro escaped to Canusium along with any other survivors; among them the young Publius Cornelius Scipio who would meet Hannibal at Zama 14 years later and become known as Scipio Africanus.

Bust Formerly Attributed to Scipio Africanus

Hannibal now declared total war on Rome. Carthage, finally rousing to some interest in her general's continual pleas for men and supplies, sent him some meager reinforcements and aid. The Romans called every able-bodied citizen to arms; the veterans of Cannae refused any pay as did the new recruits. Hannibal, however, felt his force of 40,000 was too little to take Rome and continued his policy of small engagements and winning over the minor cities to his cause. One of his aides famously remarked to him, “You know how to win a victory, Hannibal, but you do not know how to use it” (Durant, 52). After his stunning success at Cannae, it was expected that Hannibal would press his advantage and destroy his enemy completely.

While it is understandable how one would conclude this after the brilliant win at Cannae, Hannibal was actually right. He did not have enough men to take Rome and, even if he had, did not have the resources to hold it. Bradford notes:

Hannibal was now the undisputed master of the land, free to ravage and roam wherever the inclination took him. But his army, reconstituted as it was, remained an army of conquest, with no capacity for conducting siege warfare. He had no siege train – with its storming towers, its battering rams and its catapults, nor indeed any technicians for this kind of work – all of which were essential in order to reduce cities and garrisons and hold down a countryside. Already, at what seemed a point of triumph, the essential weakness of Hannibal's position was made clear: he could conquer but not consolidate. (93-94)

Hannibal, like his father before him, was constantly asking Carthage for help in winning their war for them and, just as they had with Hamilcar, Carthage refused to provide what was necessary for total victory. Rome, at this time, was weak and, further, was paralyzed with terror after their defeat at Cannae. Had Carthage acted on Hannibal's requests, the Second Punic War could have ended with a Carthaginian victory over Rome. Instead, they sent only as much aid as would not inconvenience them and Hannibal had no choice but to fight those battles which he felt he could win.

Conclusion

After Cannae, Hannibal won almost every other engagement in Italy, but they were all minor actions which gained no further ground. In the meantime, his brother, Hasdrubal, who had taken command of the Carthaginian forces in Spain, had been killed and his army dispersed after the Battle of the Metaurus in 207 BCE. All of the victories Hannibal had won for the Carthaginian cause in Spain and Italy were lost and, when Scipio invaded North Africa from Sicily in 205, Hannibal was called home, thus losing all the ground he had gained in Italy.

At the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE, Hannibal's forces were defeated by Scipio Africanus and Carthage fell to Rome. Although a brilliant strategist and general, Hannibal was finally defeated, not on the field, but by the government whose interests he had fought for. After Zama, Hannibal continued to serve his countrymen until they turned on him and falsely accused him to the Romans of attempting to build up an army to start another war. Hannibal fled Carthage, and when he felt the Romans were finally closing in on him, he took his own life in 183 BCE.

When Carthage lost the Second Punic War, they found themselves again indebted to Rome and forced to pay another indemnity for the next 50 years. After the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE), brought about by this loss and the stipulations of the treaty they had signed, Carthage, again defeated, was destroyed by the Romans. Their defeat could have easily been avoided if the Carthaginian government had been more willing to pay the price for victory; instead they were forced to pay the crushing indemnity for defeat.

Bibliography

Bradford, E. Hannibal. Dorset Press, 2010.

Durant, W. Caesar and Christ. Simon & Schuster, 1980.

Livy, Titus & De Selincourt, Aubrey & Oakley, Stephen. Livy's Histories. Penguin Classics, 2002.

Matyszak, P. The Enemies of Rome. Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Mellor, R. The Historians of Ancient Rome. Routledge, 2012.

Michael G. Readings in the Classical Historians. Scribner, 1993.

Miles, R. Carthage Must Be Destroyed. Penguin Books, 2012.

Plutarch. Plutarch's Lives. Harvard University Press, 2010.

Polybius. Polybius' Histories. Loeb Classical Library, 1992.

Warmington, B. H. Carthage: A History. Barnes & Noble Inc, 2000.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

About the Author

Joshua J. Mark

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/290/the-price-of-greed-hannibals-betrayal-by-carthage/