Cyrus the Great (558-530 BCE) built the first universal empire, stretching from Greece to the Indus River. This was the famous Achaemenid Dynasty of Persia. An inscription at Naqsh-i-Rustam, the tomb of his able successor Darius I (521-486 BCE), near Persepolis, records Gadara (Gandhara) along with Hindush (Hindus, Sindh) in the long list of satrapies of the Persian Empire.

By about 380 BC the Persian hold on Indian regions slackened and many small local kingdoms arose. In 327 BCE Alexander the Great overran the Persian Empire and located small political entities within these territories. The next year, Alexander fought a difficult battle against the Indian monarch Porus near the modern Jhelum River. East of Porus' kingdom, near the Ganges River, was the powerful kingdom of Magadha, under the Nanda Dynasty.

Plutarch (46 – 120 CE) was a Greek historian, biographer and essayist, known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia. He gives an interesting description of the situation:

As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse, they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs, its depth a hundred fathoms, while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at arms and horsemen and elephants.

Exhausted and frightened by the prospect of facing another giant Indian army at the Ganges River, his army mutinied at the Hyphasis (modern Beas River), refusing to march further East. Alexander left behind Greek forces which established themselves in the city of Taxila, now in Pakistan.

After the death of Alexander in 323 BCE, Seleucus was nominated as the satrap of Babylon in 320 BCE. Antigonus forced Seleucus to flee from Babylon, but, supported by Ptolemy, he was able to return in 312 BCE. Seleucus' later conquests include Persia and Media. He invaded what is now Punjab in northern India and Pakistan in 305 BCE.

Early allusion to the Greeks in India

Long before the arrival of Alexander the Great on India's north-western border, there are references in early Indian literature calling the Greeks Yavanas. Pāṇini, an ancient Sanskrit grammarian, was acquainted with the word yavana in his composition. Katyaanaa explains the term yavanānī as the script of the Yavanas. Nothing much is known about Pāṇini's life, not even the century he lived in. The scholarly mainstream favours 4th century BCE. Pāṇini's grammar, known as Ashtadhyayi , meaning eight chapters, defines classical Sanskrit, so that Pāṇini by definition lived at the end of the Vedic period: An important hint for the dating of Pāṇini is the occurrence of the word yavanānī (in 4.1.49, either "Greek woman", or "Greek script"). It is unlikely there would have been first-hand knowledge of Greeks in Gandhara before the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 330s BCE, but it is likely that the name was known via the Old Persian word yauna, so that the occurrence of yavanānī taken in isolation allows for as early as 520 BC, i.e. the time of Darius the Great's conquests in India.

Katyayana (3rd century BCE) was Sanskrit grammarian, mathematician and Vedic priest who lived in ancient India. He explains the term yavanānī as the script of the Yavanas. He takes the same line as above that the Old Persian term yauna became Sanskrtised to name all Greeks. In fact, this word appears in the Mahabharata.

Hellenization: The Cultural Legacy

The start of the so-called Hellenistic Period is usually taken as 323 BCE, the year of death of Alexander in Babylon. During the previous decade of invasion, he had conquered the whole Persian Empire, overthrowing King Darius. The conquered lands included Asia Minor, the Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Media, Persia and parts of modern Afghanistan, Pakistan and parts of the steppes of central Asia, almost the entire earth known to the Greeks at that time.

The Empire of Alexander the Great

As Alexander marched deeper into the East, distance alone presented him with a serious problem: how was he to remain in touch with the Greek world left behind? A physical link was vital as his army drew supplies and reinforcement from Greece and, of course, Macedonia. He had to be sure he was never cut off. He thought of a unique plan.

He went on planting military colonies and cities in strategic places. At those places Alexander left Greek mercenaries and Macedonian veterans who were no longer involved in active campaign. Besides keeping the supply routes open, those settlements served the purpose of dominating the countryside around them.

Their military significance apart, Alexander's cities and colonies became powerful instruments in the spread of Hellenism throughout the East. Plutarch described Alexander's achievements:

Having founded over 70 cities among barbarian peoples and having planted Greek magistracies in Asia, Alexander overcame its wild and savage way of life.

Alexander had indeed opened the East to an enormous wave of immigration, and his successors continued his policy by inviting Greek colonists to settle in their realms. For seventy-five years after Alexander's death, Greek immigrants poured into the East. At least 250 new Hellenistic colonies were set up. The Mediterranean world had seen no comparable movement of peoples since the days of Archilochus (680 - 645 BCE) when wave after wave of Greeks had turned the Mediterranean basin into a Greek-speaking region.

One concrete and almost exotic example of these trends comes from the newly discovered Hellenistic city of Ay Khanoum. Situated on the borders of Russia and Afghanistan and not far from China, the city was mostly Greek. It had the typical Greek trappings of a gymnasium, a choice of temples, and administration buildings. It was not, however, purely Greek. It also contained an oriental temple and artistic remains that showed that the Greeks and the natives had already embraced aspects of each other's religions. One of the most curious discoveries was a long inscription written in Greek verse by Clearchus, a pupil of Aristotle. The inscription, carved in stone, was put up in a public place for all to see. Clearchus had simply copied the precepts of famous Greeks. The inscription was philosophy for the common people, a contribution to popular culture. It provided the Greeks with a link to their faraway homeland. It was also an easy way to make at least some of Greek culture available to residents.

Alexander's settlement of Greek colonists and culture in the east resulted in a new Hellenistic culture, aspects of which were evident until the mid-15th century CE. The overall result of Alexander's settlements and those of his successors was the spread of Hellenism as far east as India. Throughout the Hellenistic period, Greeks and Easterners became familiar with and adapted themselves to each other's customs, religions, and ways of life. Although Greek culture did not entirely conquer the East, it gave the East a vehicle of expression that linked it to the West. Hellenism became a common bond among the East, peninsular Greece, and the western Mediterranean. This pre-existing cultural bond was later to prove quite valuable to Rome, itself strongly influenced by Hellenism in its efforts to impose a comparable political unity on the known world.

Hellenization is a term coined by the German historian Johann Gustav Droysen to denote the spread of Greek language, culture, and population into the former Persian Empire after Alexander's conquest. That this export took place is certain, and can be seen in the great Hellenistic cities such as Alexandria in Egypt (one of around twenty towns founded by Alexander), Antioch in modern Syria and Seleucia south of modern Baghdad. However, just how widespread and deeply permeating this was, and to what extent it was a conscious policy, is debatable. Alexander's successors openly rejected such policies after his death.

Trade in the Hellenic World

In many respects the Hellenistic city resembled a modern city. It was a cultural centre with theatres, temples, and libraries. It was a seat of learning, home of poets, writers, teachers, and artists. It was a place where people could find amusement. The Hellenistic city was also an economic centre that provided a ready market for grain and produce raised in the surrounding countryside. The city was an emporium, scene of trade and manufacturing. In short, the Hellenistic city offered cultural and economic opportunities but did not foster a sense of united, integrated enterprise.

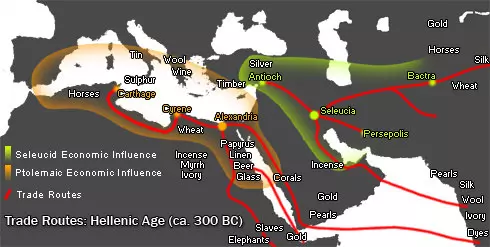

The Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties traded as far afield as India, Arabia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Overland trade with India and Arabia was conducted by caravan and was largely in the hands of Easterners. The caravan trade never dealt in bulk items or essential commodities; only luxury goods could be transported in this very expensive fashion. Once the goods reached the Hellenistic monarchies, Greek merchants took a hand in the trade.

Essential to the caravan trade from the Mediterranean to Afghanistan and India were the northern route to Dura on the Euphrates River and the southern route through Arabia. The desert of Arabia may seem at first unlikely and inhospitable terrain for a line of commerce, but to the east of it lay the plateau of Iran, from which trade routes stretched to the south and still farther cast to China. Commerce from the East arrived in Egypt and at the excellent harbours of Palestine, Phoenicia, and Syria. From these ports goods flowed to Greece, Italy, and Spain. The backbone of this caravan trade was the camel - shaggy, ill-tempered, but durable.

Hellenistic Trade Routes, 300 BCE

Over the caravan routes travelled luxury goods that were light, rare, and expensive. In time these luxury items became more of a necessity than a luxury. In part this development was the result of an increased volume of trade. In the prosperity of the period more people could afford to buy gold, silver, ivory, precious stones, spices, and a host of other easily transportable goods. Perhaps the most prominent goods in terms of volume were tea and silk. Indeed, the trade in silk gave the major route the name "Silk Road", for not only was this route prominent in antiquity, but it was used until early modern times. In return the Greeks and Macedonians sent east manufactured goods, especially metal weapons, cloth, wine, and olive oil.

Although these caravan routes can trace their origins to earlier times, they became far more prominent in the Hellenistic period. Business customs developed and became standardized, so that merchants from different nationalities communicated in a way understandable to all of them.

Innovative years on the borders of India

There was a succession of more than thirty Hellenistic kings, often in conflict with each other, from 180 BC to around 10 CE. This era is known as the Indo-Greek kingdom in the pages of history. The kingdom was founded when the Greco-Bactrian King Demetrius invaded India in 180 BCE, ultimately creating an entity which seceded from the powerful Greco-Bactrian kingdom centred in Bactria (today's northern Afghanistan). Since the term "Indo-Greek Kingdom" loosely described a number of various dynastic polities, it had several capitals, but the city of Taxila in modern Pakistan was probably among the earliest seats of local Hellenic rulers, though cities like Pushkalavati and Sagala (apparently the largest of such residences) would house a number of dynasties in their times.

During the two centuries of their rule, the Indo-Greek kings combined the Greek and Indian languages and symbols, as seen on their coins, and blended ancient Greek, Hindu and Buddhist religious practices, as seen in the archaeological remains of their cities and in the indications of their support of Buddhism. The Indo-Greek kings seem to have achieved a level of cultural syncretism with no equivalent in history, the consequences of which are still felt today, particularly through the diffusion and influence of Greco-Buddhist art.

According to Indian sources, Greek ("Yavana") troops seem to have assisted Chandragupta Maurya in toppling the Nanda Dynasty and founding the Mauryan Empire. By around 312 BCE Chandragupta had established his rule in large parts of the north-western Indian territories as well.

In 303 BCE, Seleucus I led an army to the Indus, where he encountered Chandragupta. Chandragupta and Seleucus finally concluded an alliance. Seleucus gave him his daughter in marriage, ceded the territories of Arachosia (modern Kandahar), Herat, Kabul and Makran. He in turn received from Chandragupta 500 war elephant which he used decisively at the Battle of Ipsus.

The peace treaty, and "an intermarriage agreement" (Epigamia, Greek: Επιγαμια), meaning either a dynastic marriage or an agreement for intermarriage between Indians and Greeks was a remarkable first feat in this campaign.

Megasthenes, first Greek ambassador

Megasthenes (350 – 290 BCE) was a Greek ethnographer in the Hellenistic period, author of the work Indica. He was born in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey) and became an ambassador of Seleucus I to the court of Sandrocottus, who possibly was Chandragupta Maurya in Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar state), India. However the exact date of his embassy is uncertain. Scholars place it before 288 BCE, the date of Chandragupta's death.

At the start of the Indica, Megasthenes talks about the older Indians who knew about the prehistoric arrival of Dionysus and Hercules in India. This story was quite popular amongst the Greeks during the Alexandrian period. He describes geographical features of India, such as the Himalayas and the island of Sri Lanka.

Especially important are his comments on the religions of the Indians. He mentions the devotees of Hercules (Shiva) and Dionysus (Krishna or Indra), but he does not write a word on Buddhists, something that gives ground to the theory that Buddhism was not widely spread in India before the reign of Asoka (269 BCE to 232 BCE).

Indica served as an important source to many later writers such as Strabo and Arrian. The 1st century BCE Greek historian Apollodorus, quoted by Strabo, affirms that the Bactrian Greeks, led by Demetrius I and Menander, conquered India and occupied a larger territory than the Macedonians under Alexander the Great, going beyond the Hyphasis (modern Beas River) towards the Himalayas.

Indo-Greek Campaigns

The Roman historian Justin also cited the Indo-Greek conquests, describing Demetrius as "King of the Indians" ("Regis Indorum"), and explaining that Eucratides in turn "put India under his rule" ("Indiam in potestatem redegit"). "India" only meant the upper Indus for Alexnder the Great. Since the appearance of Megasthenes, "India" meant to the Greeks most of the northern half of the Indian subcontinent. Greek and Indian sources tend to indicate that the Greeks campaigned as far as Pataliputra until they were forced to retreat following a coup in Bactria in 170 BCE.

Appearance of coins as the first landmark

It is really difficult to know today where the idea of coinage first evolved. Based on available evidences, it appears that the notion of money (as coins, which by definition here would be a piece of metal of defined weight stamped with symbol of authority for financial transaction), was conceived by three different civilizations independently and almost simultaneously. Coins were introduced as a means to trade things of daily usage in Asia Minor, India and China in 6th century BC. Most historians agree that the first coins of world were issued by Greeks living in Lydia and Ionia (located on the western coast of modern Turkey). These first coins were globules of Electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. These were crude coins of definite weight stamped with punches issued by the local authorities in about 650 BCE.

Both, literary and archaeological evidence confirm that the Indians invented coinage somewhere between the 5th and 6th centuries BCE. A hoard of coins discovered at Chaman Huzuri in 1933 CE contained 43 silver punch-marked coins (the earliest coins of India) mixed with Athenian (coins minted by Athens city of Greece) and Achaemenid (Persian) coins. The Bhir (Taxila in modern Pakistan) hoard discovered in 1924 CE contained 1055 punch-marked coins in very worn-out condition and two coins of Alexander in mint condition. This archaeological evidence clearly indicates that the coins were minted in India long before the 4th century BCE — i.e. before Greeks advanced towards India. Pānini wrote his Ashtadhyayi in the 4th or 5th century BCE in which he mentioned Satamana, Nishkas, Sana, Vimastika, Karshapana and its various sub-divisions to be used in financial transactions. Thus, coins were known in ancient Indian literature from 500 BCE. There is also a strong belief that silver as a metal which was not available in Vedic India (pre 600 BCE). It became abundantly available by 500-600 BCE. Most of the silver came from Afghanistan and Persia as a result of international trade.

The first Greek coins to be minted in India, those of Menander I and Appolodotus I bear the mention "Saviour king" (BASILEOS SOTHROS), a title with high value in the Greek world. For instance, Ptolemy I had been Soter (saviour) because he had helped save Rhodes from Demetrius the Besieger, and Antiochus I because he had saved Asia Minor from the Gauls. The title was also inscribed in Pali (the Kharoṣṭhī script) as Tratarasa on the reverse of their coins. Menander and Apollodotus may indeed have been saviours to the Greek populations residing in India.

Most of the coins of the Greek kings in India were bilingual, written in Greek on the front and in Pali on the back, a superb concession to another culture never before made in the Hellenic world. From the reign of Apollodotus II, around 80 BCE, Kharoshthi letters started to be used as mintmarks on coins in combination with Greek monograms and mintmarks. It suggested the participation of local technicians to the minting process. Incidentally, these bilingual coins of the Indo-Greeks were the key in the decipherment of the Kharoṣṭhī script by James Prinsep (1799 –1840 CE).

The Kharoṣṭhī script, is an ancient abugida (or "alphasyllabary") used by the Gandhara culture, nestled in the historic northwest South Asia to write the Gāndhārī and Sanskrit languages. It was in use from the middle of the 3rd century BCE until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE. It was also in use in Kushan, Sogdiana and along the Silk Road where there is some evidence it may have survived until the 7th century CE in the remote way stations of Khotan and Niya.

The coinage of the Indo-Greeks remained in fact influential for several centuries throughout the Indian subcontinent:

The Indo-Greek weight and size standard for silver drachms was adopted by the contemporary Buddhist kingdom of the Kunindas in Punjab, the first attempt by an Indian kingdom to produce coins that could compare with those of the Indo-Greeks.

In central India, the Satavahanas (2nd century BCE- 2nd century CE) adopted the practice of representing their kings in profile, within circular legends.

The direct successors of the Indo-Greeks in the northwest, the Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians continued displaying their kings within a legend in Greek, and on the obverse, Greek deities.

To the south, the Western Kshatrapas (1st-4th century CE) represented their kings in profile with circular legends in corrupted Greek.

The Kushans (1st-4th century CE) used the Greek language on their coinage until the first few years of the reign of Kanishka, whence they adopted the Bactrian language, written with the Greek script.

The Guptas (4th-6th century CE), in turn imitating the Western Kshatrapas, also showed their rulers in profile, within a legend in corrupted Greek, in the coinage of their western territories.

The latest use of the Greek script on coins corresponds to the rule of the Turkish Shahi of Kabul, around 850 CE.

Rise of Menander

Menander (Milinda), originally a general of Demetrius, is probably the most successful Indo-Greek king, and the conqueror of the vastest territory. The finds of his coins are the most numerous and the most widespread of all the Indo-Greek kings. From at least the 1st century AD, the "Menander Mons", or "Mountains of Menander", came to designate the mountain chain at the extreme east of the Indian subcontinent, today's Naga Hills and Arakan, as indicated in the Ptolemy world map of the 1st century. Menander is also remembered in Buddhist literature (the Milinda Panha) as a convert to Buddhism: he became an arhat (Buddhist ascetic) whose relics were enshrined in a manner reminiscent of the Buddha. He also introduced a new coin type, with Athena Alkidemos ("Protector of the people") on the reverse, which was adopted by most of his successors in the East.

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/208/cultural-links-between-india--the-greco-roman-worl/