Richard III of England

Richard III of England, National Portrait Gallery

Richard III of England ruled as king from 1483 to 1485 CE. Richard succeeded Edward V of England (r. Apr-Jun 1483 CE), the son of Edward IV of England (r. 1461-1470 CE & 1471-1483 CE) in mysterious circumstances. The young Edward V and his brother Richard were imprisoned in the Tower of London by their uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester who was their guardian as Protector of the Realm. The Princes in the Tower, as they became known, were never seen again. Duke Richard made himself king in 1483 CE but, widely accused of murdering his nephews and unable to unite his barons behind the Crown, his reign would be short and troubled. The dynastic squabbles between the houses of York and Lancaster known to history as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE) finally came to an end, in terms of major events, with Richard's death at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 CE. Henry Tudor, a distant relation of Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE) and victor at Bosworth Field, would become King Henry VII (r. 1485-1509 CE). The Plantagenet line of kings, which had started with Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE), was finally ended and the new Tudor Dynasty began.

Early Life & Family

Richard was born on 2 October 1452 CE at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, the son of Richard, Duke of York (1411-1460 CE) and Cecily Neville (1415-1495 CE). His older brothers included Edward who would become Edward IV of England and George, Duke of Clarence (l. 1449-1478 CE). Richard lived in exile in Burgundy after his father's death in 1460 CE. When he returned to England the next year he lived with the family of the Earl of Warwick at Middleham Castle in the north of England.

WITH HENRY VI MURDERED, HIS QUEEN IMPRISONED & HIS SON KILLED IN BATTLE, IT LOOKED LIKE THE YORKS HAD WON THE WARS OF THE ROSES.

On 12 July 1472 CE Richard married Anne Neville (l. 1456-1485 CE), the daughter of the Earl of Warwick and widow of Henry VI of England's son, Edward, Prince of Wales (l. 1453-1471 CE). This union meant that Richard acquired a sizeable chunk of the dead Earl of Warwick's estates. The couple had one son, Edward of Middleham, born in 1473 CE (or 1476 CE) and made Prince of Wales in 1483 CE.

Wars of the Roses

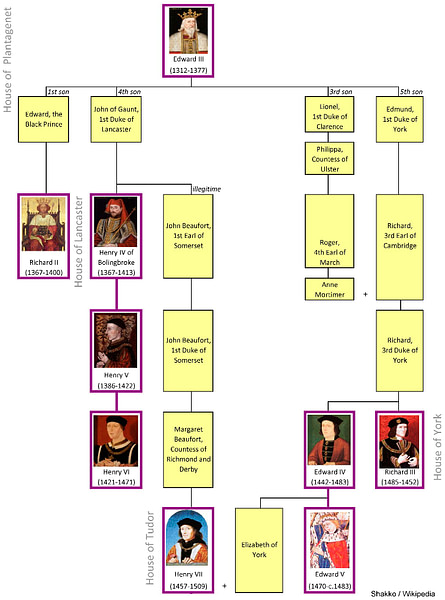

In 1453 CE Henry VI of England (1422-1461 CE & 1470-1471 CE) suffered his first episode of insanity which made him so incapable of ruling that Richard, Duke of York was nominated as Protector of the Realm, in effect, regent, in March 1454 CE. The Duke of York was ambitious to become king and he did have a legitimate, if distant, claim to the throne as the great-grandson of Edward III of England and the nephew of the Earl of March who himself had claimed he was the legitimate heir to Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE). Thus, a rivalry began between the house of York and that of Lancaster, of which King Henry VI was a member, a rivalry that became known as the Wars of the Roses.

Family Tree of House Lancaster & York

Richard might have had the king in his pocket but he still had the formidable obstacle of Henry's wife Queen Margaret (d. 1482 CE) and she led an army to victory against him at the Battle of Ludford Bridge on 12 October 1459 CE. The Duke of York fled to Ireland while Parliament, the 1459 CE 'Parliament of Devils', identified him as a traitor and disinherited his heirs. Richard's son Edward then took up the cause with his chief ally Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick (1428-71 CE), the pair defeating Queen Margaret's army at Northampton on 10 July 1460 CE and then capturing King Henry. The Duke of York was thus able to return from Ireland and he persuaded Henry, who was now in the Tower of London, to name him as the official heir to the throne, a decision ratified by the Act of Accord of 24 October. However, at the Battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460 CE the Duke of York was killed and his army defeated by Henry VI loyalists led, once again, by the queen.

RICHARD, DUKE OF GLOUCESTER, HAD SHOWN HIMSELF AN ABLE COMMANDER & HIS LOYALTY TO HIS BROTHER EDWARD IV WAS RESOLUTE THROUGH TURBULENT TIMES.

The Duke of York's son, now Edward of York, took up the Yorkist mantle from 1460 CE. Following his victory at the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1461 CE, Edward was crowned Edward IV on 28 June 1461 CE. There would be a brief interruption when his old ally the Earl of Warwick reinstated Henry VI in 1470 CE and Edward was obliged to flee in exile to France, accompanied by his brother Richard. Edward would soon win back his throne, though, again on the battlefield, this time at Barnet on 14 April 1471 CE. Henry VI was then murdered in the Tower of London on 21 May 1471 CE. With Henry's young heir, Prince Edward, killed at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May 1471 CE and Queen Margaret imprisoned, it looked like the Yorks had finally won the Wars of the Roses.

Duke of Gloucester

In 1472 CE Edward made his brother Richard the Duke of Gloucester in thanks for his successful command of divisions at the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury the year before. This was in addition to Richard's other titles of Constable and Lord High Admiral (bestowed in 1471 CE). Richard had shown himself an able commander and his loyalty to his brother was resolute throughout the turbulent times of the Wars of the Roses.

Edward IV of England & Lancastrian Fugitives at Tewkesbury Abbey

As lord of vast estates, Richard showed himself a fine administrator and he was popular with both his peers and subjects. Richard was also surprisingly pious, the duke giving an endowment to Queen's College, Cambridge so that prayers might be said for his fallen comrades at Barnet and Tewkesbury. Richard was interested in architecture and donated to both state and religious institutions, a trend he would continue as king, notably establishing the Royal College of Arms in 1484 CE which looked after all matters of medieval heraldry and which still continues to function today. Richard's own heraldic device was a white boar.

Edward IV's reign saw much more stability and a booming economy thanks to a peace treaty with France and the encouragement of cross-Channel trade. A peace treaty was signed with Louis XI of France (1461-1483 CE) in March 1475 CE after Edward and the Duke of Gloucester had led a large army to France. Another success was a sortie into Scotland in 1482 CE, led by the Duke of Gloucester, which occupied Edinburgh for a time. The campaign won back control of Berwick for the English Crown.

All was not well in England, though, and cracks soon began to appear in the relationship between the king and his brothers. Richard was not convinced that peace with France was the best policy and then, in February 1478 CE, the third brother, George, Duke of Clarence, was imprisoned and executed on charges of treason. Richard perhaps felt that Edward's wife, Elizabeth Woodville (l. c. 1437-1492 CE), was to blame for dividing the York family and favouring her own relatives. After this episode, Richard concentrated on his land in the north of England and stayed away from the royal court in London. Still, the Scottish campaign gained Edward's gratitude and Richard was made Warden of the West March by parliament in 1483 CE and given sovereign powers over that territory.

The Princes in the Tower

Edward IV turned out to be rather too fond of his favourite foods and wines as he reached middle age, and he became seriously overweight. The king died, perhaps of a stroke, at Westminster on 9 April 1483 CE, aged just 40. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Edward, then only 12 years old (b. 1470 CE). Too young to rule on his own, Edward IV had already nominated his regent, the boy's uncle Richard, who was now given the impressive title of Lord High Protector of the Realm.

The Princes in the Tower

In May, Edward V and his younger brother Richard (b. 1473 CE) were imprisoned in the Tower of London where they became known as the 'Princes in the Tower'. The boys were never seen outside the castle again. According to later historians and Tudor propaganda, the boys were put there and murdered by Richard. This is also the view of William Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE) in his famous play Richard III. What we do know is that the two princes did spend time in the Tower - which was not merely a prison for important figures but a royal residence - and that they were seen by witnesses playing in the gardens there. Richard may have confined them there to forestall Queen Elizabeth's plan to hold an early coronation for Edward in June. A coronation could well have meant Richard's title and function as Protector of the Realm was withdrawn.

THE SUPPOSED MURDER OF THE PRINCES IN THE TOWER RESULTED IN THE FINGER OF SUSPICION POINTING AT RICHARD.

The duke's first tactic was to discredit the legitimacy of the two princes by claiming that Edward IV had already been tied by a marriage agreement to one Lady Eleanor Butler, daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury before he married Elizabeth Woodville. The late king's promiscuity was well known, and this at least allowed enough doubt in the case that Parliament declared Edward V and his younger brother illegitimate. Consequently, Edward was deposed on 25 June 1483 CE and Richard was nominated as the legitimate heir to the throne. The Duke of Gloucester, aged 30, was then crowned king on 6 July 1483 CE in Westminster Abbey, thereby becoming Richard III.

Then, sometime in the late summer of 1483 CE, the princes disappeared from the Tower and history, their obvious murder resulting in the finger of suspicion pointing at Richard. Curiously, Richard had been on duty in the Tower of London the night of Henry VI's murder and he was suspected of having done many other dark deeds to progress his career. Nevertheless, the deaths of the princes still remains a mystery. As a footnote to this grizzly episode, two skeletons of youths were discovered in a chest buried near the White Tower when the forebuilding was demolished in 1674 CE and these remains, identified then as the two princes, were reinterred in Westminster Abbey. The remains were re-examined in 1933 CE and confirmed as young males of similar age to the princes. Whoever killed the boys, Richard undoubtedly had most to gain by their deaths. Edward V was certainly the unlucky 13th king in the Plantagenet line.

Henry Tudor

There were some voices of protest, even from Yorkist supporters, regarding Richard's cavalier attitude to royal succession but these were dealt with in time-honoured fashion via land confiscation and executions. However, trouble of a much greater significance was stirring. The Lancastrians were weak, but the family had not gone away entirely, and they were now led by the exiled Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond (b. 1457 CE). Henry was, through the illegitimate Beaufort line, a descendant of John of Gaunt, a son of Edward III. It was not much of a royal connection but it was the best the Lancastrians could hope for after Henry VI had left no surviving heir.

Henry Tudor allied himself with the alienated Woodvilles, such powerful lords as the Duke of Buckingham who were not happy with Richard's distribution of estates, and anyone else keen to see Richard III receive his just deserts. These allies included the new king across the Channel, Charles VIII of France (r. 1483-1498 CE). The first move by the rebels proved premature and poorly planned so that Henry's invasion fleet was put off by bad weather and Buckingham was captured and executed in November 1483 CE.

The next twist in the Wars of the Roses was the death of Edward, Richard III's son and heir on 9 April 1484 CE, and once more the Lancastrians saw a glimmer of opportunity. Richard was dealt another blow in March 1485 CE when his queen, Anne Neville, died after a long illness. The king's detractors spread rumours that Anne had been murdered - presumably by a slow-working poison - so that Richard could be free to marry the eldest daughter of Edward IV, his own niece, and so prevent Henry Tudor from doing so and strengthening his own royal links.

Government & Administration

Meanwhile, Richard had been attempting to cement his kingship by travelling extensively around his kingdom, and in July 1484 CE he created the Council of the North which had full powers to govern that region in the king's name. Another new body was the Council of Requests and Supplications, created to give poor people greater access to the justice system. The king also made the collection of royal incomes more efficient, one of the problems Edward IV had been advised to deal with urgently. Finally, Richard encouraged the only Parliament he called, in January 1484 CE, to enact new laws which sought to reduce corruption by local officials and courts, end the practice of forced loans and make the selection of jurors a stricter process. All of these measures indicate the king may have developed into a good one for his people if he were given time. Unfortunately, time was not on Richard's side as Henry Tudor now made his gamble for the throne.

Bosworth Field & Death

On 8 August 1485 CE, the Wars of the Roses reached boiling point when Henry Tudor landed with an army of French mercenaries at Milford Haven in South Wales, a force perhaps no bigger than 5,000 men. Henry's army swelled in numbers as it marched to face the king's army at Bosworth Field in Leicestershire on 22 August 1485 CE. Richard, although commanding an army of some 8,000-12,000 men, was, at the last moment, deserted by some of his key allies, and the Earl of Northumberland even refused to engage his troops until he had a clear idea which side was going to win the day. Nevertheless, the king fought bravely and perhaps a little foolishly in his efforts to kill Henry Tudor with his own sword. Richard, although managing to strike down Henry's standard-bearer, had his horse cut from under him - hence, Shakespeare's famous line "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!" (Act 5, Scene IV) - and the king was killed. Richard was the last English monarch to fall on the battlefield. The dead king's body was displayed naked except for a piece of cloth in the Church of Saint Mary in Newarke near the battleground and then buried at Greyfriars Abbey, Leicester.

Skeleton of Richard III of England

Richard III has gone down in history as possibly England's most villainous and despised king. A large contribution to this dark portrait was Shakespeare's Richard III where the king is an unprincipled hunchback and given lines like "I am determined to prove a villain" (Act 1, Scene 1) and "Thus I clothe my naked villany. With odds old ends stol'n forth of holy writ, And seem a saint when most I play the devil" (Act 1, Scene 3). The king is even visited by a long succession of ghosts, the restless spirits of all the significant people Richard had supposedly killed.

The Tudor historians also put it about that Richard was favoured by the Devil, which explained why he came out of his mother's womb feet first, was born with teeth already, had a couple of fingers missing and developed a taste for murder. These stories do not match Richard's contemporary portraits or the trust and goodwill extended to him by Edward IV and many of the people who were governed by him in the north of England. Finally, it is a possibility that the Princes of the Tower episode, Richard's most infamous crime, were actually still alive after the Battle of Bosworth Field and it was Henry Tudor who had them killed. Certainly, if Edward V had been still alive then he would have been a serious obstacle to Henry's claim to be king.

The victorious Henry Tudor, according to legend, was given Richard's crown, found by Lord Stanley beneath a hawthorn bush at Bosworth Field. The new king was crowned Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE) on 30 October 1485 CE and, marrying Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV in 1486 CE, the two rival houses were finally united and a new one created: the Tudors. The battles of the Wars of the Roses were (almost) over, half the English barons had been killed in the process, but England was at last united as it left the Middle Ages and headed into the modern era.

Richard III was not quite finished with the history books, though. In 2012 CE archaeologists in Leicester excavated the site where they believed the ruins of Greyfriars Abbey were now buried. Digging down from what was on the surface a car park, they revealed a skeleton which was male, had many marks of sword or dagger injuries and, most intriguingly, had suffered from curvature of the spine. Curiously, the skeleton, found beneath the choir of the ruined friary, had been directly below a reserved parking space in the modern-day car park on which was marked the letter R. Researchers at the University of Leicester conducted DNA testing and confirmed that, with a probability of 99.9%, this was the skeleton of Richard III. The remains were eventually reinterred in a new purpose-built tomb in Leicester Cathedral.

Bibliography

Cannon, J. The Kings and Queens of Britain. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Cavendish, R. Kings & Queens. David & Charles, 2007.

Crouch, D. Medieval Britain, c.1000-1500. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Gravett, C. English Medieval Knight 1400-1500. Osprey Publishing, 2001.

Hicks, M. The War of the Roses. Osprey Publishing, 2003.

Jones, N. Tower. Griffin, 2013.

Phillips, C. The Complete Illustrated Guide to the Kings & Queens of Britain. Lorenz Books, 2006.

Ralph Lewis, B. Kings and Queens of England. Readers Digest, 2003.

Saul, N. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval England. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Shakespeare, W. The Complete Works. Oxford University Press, 1945

Starkey, D. Crown and Country. HarperPress, 2011.

The Discovery of Richard III by the University of LeicesterAccessed 7 Feb 2020.

Turvey, R. Lancastrians, Yorkists and the Wars of the Roses, 1399-1509. Hodder Education Publishers, 2015.

Wilson, D. Plantagenets. Quercus, 2011.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Richard_III_of_England/