The Great Amazigh Revolt-1-

Turbulent period

In the 13th century, between the end of the Umayyad caliphate (661-750) in Damascus and the Idrissid dynasty (789-985), a period of great turbulence took place in North Africa: the revolt of the Amazighs.

From the beginning of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb (647-709), the Berbers resented Arab domination. Indeed, Amazigh society was based on a community structure that placed great importance on equality. They quickly revolt against the Arabs. The Arab elite set up a system of precedence which guaranteed them preferential treatment. This elite fought hard to establish and maintain the mechanisms that distinguished Muslims from each other and alienated their relatively new allies in northwest Africa.

The crisis began when Maysara, the Berber leader, led a delegation of 40 people to Caliph Hisham (691-743) in 739 to present the grievances of the Amazighs: equality in the sharing of spoils and an end to the practice of evisceration of ewes to obtain fetal fur. Complaints reach the caliph but he gives no response, which triggers the revolt in Tangier. Maysara seizes the city, kills the governor Omar Ibn Abdallah and proclaims himself caliph. He succeeded in preventing the landing of an Umayyad army sent from Spain.

The Great Amazigh Revolt of 739/740-743 AD (122-125 AH in the Muslim calendar) took place during the reign of Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik[ii] (691-743) and marked the first secession successful within the Arab Caliphate (ruled from Damascus). Inflamed by Puritan Kharijite preachers, the Amazigh revolt against their Arab Umayyad rulers began in Tangier in 740, and was led initially by Maysara al-Matghari. he revolt quickly spread throughout the rest of the Maghreb (North Africa) and across the straits to al-Andalus (Spain).

The Umayyads rushed in and succeeded in preventing the core of Ifriqiya (Tunisia) and al-Andalus from falling into rebel hands. But the rest of the Maghreb was never recovered. After failing to capture the Umayyad provincial capital of Kairouan, the rebel Amazigh armies disbanded and the western Maghreb fragmented into a series of small Berber states, ruled by tribal chiefs and Kharijite imams.

The Amazigh revolt was probably the greatest military setback of Caliph Hisham's reign. From this emerged some of the first Muslim states outside the Caliphate. It is sometimes also seen as the start of Moroccan independence, as Morocco would never again come under the rule of an Eastern Caliph or any other foreign power until the 20th century.

The new Muslim Amazighs, having been educated in the rudimentary message of Islam and having recognized its power, used the ideals of Islam against their conquerors and proclaimed their own interpretation of the faith. Kusayla, an Amazigh and Muslim converted king whom 'Uqba thought he had pacified, escaped from his chains and killed 'Uqba ibn Nafi' shortly after the latter's Atlantic ride. 'Uqba died in an oasis near the Algerian town of Biskra. At the same time, there are monuments to the memory of his enemies, the Amazighs Dihya (Kahina – the Berber queen) and Kusayla, who are still remembered by North African Muslims as heroes.

Arab stereotypes about the Amazigh and Arab racism

Nicolas Clarke of the University of Newcastle in England tells us in an article entitled: '''They are the most treacherous of people': religious difference in Arabic accounts of three early medieval Berber revolts'' that the conquerors Arabs, in their haughty attitude, maintained harmful stereotypes about the indigenous population of North Africa:

ʿAbd al-Malik b. Ḥabīb, a jurist and historian who died in the middle of the ninth century, concludes his account of the Muslim conquest of his native Iberia in the eighth century with a long scene of dialogue, set at the court of the Umayyad Caliphate (r. 661-750) in Damascus. The dialogue takes place between Mūsā b. Nuṣayr, the commander of the conquering armies, and Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik, who had recently succeeded his brother al-Walīd as caliph. It takes a conventional form: a series of laconic questions from the caliph (“Tell me about al-Andalus!”) are met with answers that have the sound of an aphorism. Stereotypes are omnipresent there, especially in the comments on the Berbers:

''[Sulaymān] said, “Tell me about the Berbers. [Mūsā] replied, "They are the non-Arabs who most resemble the Arabs (hum ashbah al-ʿajam bi-al-ʿarab) [in their] bravery, steadfastness, endurance and horsemanship, except that they are the most treacherous of people (al-nās) – they [have] no [care] for loyalty, nor pacts. (Ibn Ḥabīb, 148)''

In the context of the Arab elite, radical beliefs initially seemed to have great appeal for Amazighs. Although some Arab sources may have exaggerated, it seems that the early revolutionaries had a bitter reaction to unbelieving Sunni Arabs, sometimes killing indiscriminately and selling Muslim women and children into slavery, just as some Arabs had made to the Berbers during earlier conquests.

The first rebellions took place near Tangier and throughout the Muslim West, sparked, it is said, by an Arab commander who had branded his Amazigh guard with a hot iron as if they were cattle. But Amazigh rebels of the Kharijite faith mostly established their dominance in somewhat remote and easily defended outposts, such as Mount Nafusa, Sijilmasa and Tahert. Over time, even these revolutionaries settled into a routine, they founded dynasties and integrated into a larger economic system.

The main causes of the revolt are the harsh policy of the governor of North Africa, 'Ubayd Allah bin al-Habhab (who demanded that Amazigh slaves be delivered as part of the tribute paid by the Berber tribes) and discrimination against the against the Amazigh units of the Caliphal army compared to the Arab units, the former being frequently exposed to dangers that the commanders spared the latter.

For Philippe Sénac and Patrice Cressier, the Berber revolts are the result of the excesses of the Arab governors of North Africa:

''For many historians, the Berber revolts that affected the Maghreb appear as the direct consequence of the Arab conquest and the excesses committed by the Umayyad governors of Kairouan. The vast majority of the Berber tribes had rallied to Islam and they had participated in the same way as the Arab fighters in the campaigns carried out in al-Andalus and in the south of Gaul. Despite this support, however, they were subjected to humiliations by the Damascus government, particularly in the second quarter of the eighth century.

At first, the Yemeni caliphs Sulaymân (715-717) and 'Umar II (717-720) adopted a favorable attitude towards the Berber populations, but the situation deteriorated rapidly…''

The underlying causes of the revolt

The underlying causes of the revolt were the policies of the Umayyad governors of Kairouan, Ifriqiya, who had authority over the Maghreb (all of North Africa west of Egypt) and al-Andalus (Spain).

From the earliest days of the Muslim conquest of North Africa, Arab commanders had treated non-Arab (notably Amazigh) auxiliaries inconsistently and often rather meanly. Although the Berbers undertook much of the fighting during the conquest of Spain, they received a lesser share of the spoils and were often assigned to the hardest tasks (for example, they were thrown to the front -guard while the Arab forces were kept in the rear; they were assigned to garrison duty on the most troubled frontiers).

Although the Arab governor of Ifriqiya Musa ibn Nusair cultivated his Amazigh lieutenants (the most famous being Tariq ibn Ziyad), his successors, notably Yazid ibn Abi Muslim, had treated their Berber forces particularly badly. Worse still, Arab governors continued to levy extraordinary taxes on the dhimmi (the jizyah and the kharaj ) and slave tributes on non-Arab populations who had converted to Islam, in direct violation of Islamic law. This had become particularly common during the Caliphate of Sulayman (674-717).

In 718, the Umayyad Caliph Umar II (682-720) finally banned the collection of extraordinary taxes and slave tributes from non-Arab Muslims, defusing much of the tension. But costly military setbacks in the 720s and 730s had forced Caliphal authorities to seek innovative ways to replenish their treasuries. During Hisham's Caliphate from 724, the prohibitions were circumvented by reinterpretations (e.g. linking the kharaj land tax to the land rather than the owner, so that lands which were at all times subject to the kharaj remained under kharaj even though they were currently owned by a Muslim).

As a result, resentful Amazighs became receptive to radical Kharijite militants from the east (notably of Sufri and later Ibadi persuasion) who had begun to arrive in the Maghreb in the 720s. The Kharijites preached a puritanical form of Islam, promising a new political order, where all Muslims would be equal, regardless of ethnicity or tribal status, and where Islamic law would be strictly observed. The appeal of the Kharijite message to Amazigh ears enabled their militants to gradually penetrate the regiments and Berber population centers. Sporadic mutinies by Amazigh garrisons (e.g. under Munnus in Cerdanya, Spain, in 729-31) were suppressed with difficulty. An Ifriqiyan governor, Yazid ibn Abi Muslim, jizyah and humiliated his Amazigh guard by marking his hands, was assassinated in 721.

In 734, Ubayd Allah ibn al-Habhab was appointed Umayyad governor in Kairouan, with supervisory authority over the entire Maghreb (North Africa) and al-Andalus (Spain). Arriving after a period of mismanagement, Ubayd Allah quickly set about increasing the government's fiscal resources by relying heavily on non-Arab populations, taking over extraordinary taxation and slave tribute without excuse. His deputies Oqba ibn al-Hajjaj al-Saluli in Cordoba (Spain) and Omar ibn el-Moradi in Tangier (Morocco) received similar instructions. The failure of costly expeditions to Gaul during the period 732-737, repelled by the Franks under Charles Martel, only increased the tax burden. The parallel failure of the Caliphal armies in the east brought no tax relief from Damascus.

The book " Languages and Power in Algeria, History of a Linguistic Trauma ", by Mohamed Benrabah, [xxiv] reports an excerpt from a letter that Maysara sends to the Caliph of Damascus on the behavior of the Umayyad conquerors:

''Inform the Prince of the Faithful that our emir is leading us on an expedition with his jund (military province) and that he is distributing to it the booty we have made, saying that we have more than merit. If there is a city under siege, he puts us first, saying that our merit in heaven will only be greater. And yet people like us are worth his brothers! […] We put up with all this, but when afterwards they kidnapped the most beautiful of our daughters, we told them that as Muslims we do not find such an act authorized either by the Book or by the practice of the prophet…''.

The response of the Caliph of Damascus was the imposition of a tax, making the Amazighs slave enemies of Islam.

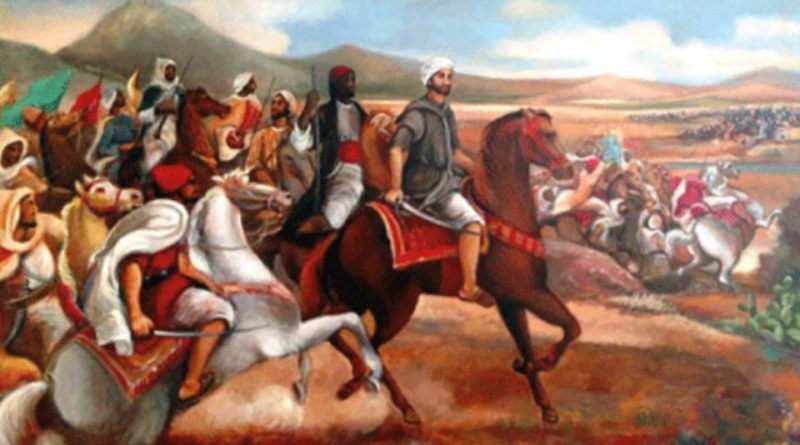

Maysara al-Matghari

Revolt in Tamazgha

The zeal of the Umayyad tax collectors eventually broke the patience of the Berbers. It is reported that following instructions from Ubayd Allah ibn al-Habhab to extract more revenue from the Amazighs, Omar ibn al-Moradi, his vice-governor in Tangier, decided to declare the Berbers under his jurisdiction a " conquered people " . and therefore proceeded to seize their possessions and reduce them to slavery, since according to the rules of the conquest, the "fifth caliphal" was still due to the Umayyad state (according to other sources, he simply doubled their tribute).

It was the straw that broke the camel's back. Inspired by Sufi preachers, the North African Amazigh tribes of western Morocco – initially the Ghomara, Berghouata and Miknasa – decided to openly revolt against their Arab overlords. They chose Maysara al-Matghari, who, according to some Arab chroniclers, was a lowly water-carrier (but more likely a high-ranking Berber leader of the Matghara tribe) as their leader. The only question that arose was that of the moment. The opportunity arose at the end of the year 739 or the beginning of the year 740 (122 AH), when the powerful general Habib ibn Abi Obeida al-Fihri, who had recently imposed his authority in the Sous valley, in southern Morocco, received instructions from the governor of Kairouan, Ubayd Allah, to lead a vast expedition across the sea against Byzantine Sicily. Gathering his forces, Habib ibn Abi Obeida marched the bulk of the army out of Morocco.

As soon as the mighty Habib was out of the country, Maysara assembled his coalition of Amazigh armies, their heads shaved in the fashion of the Kharijites and with Koranic inscriptions attached to their spears and swords, and brought them to Tangier. The city soon fell to the rebels and the hated governor Omar al-Moradi was killed. This is when Maysara is said to have taken the title and claim of amir al-mu'minin (“Commander of the Faithful” or “Caliph”). Leaving a Berber garrison in Tangier under the command of a Christian convert, Abd al-Allah al-Hodeij al-Ifriqi, Maysara's army began to sweep through western Morocco, swelling its ranks with new adherents, crushing the Umayyad garrisons from the strait to Sous. One of the local governors killed by the Amazighs was Ismail ibn Ubayd Allah, the very son of the Emir of Kairouan The Berber revolt surprised the Umayyad governor of Kairouan, Ubayd Allah ibn al-Habhab, who had only very few troops at his disposal. He immediately sent messengers to his general Habib ibn Abi Obeida al-Fihri in Sicily asking him to halt the expedition and urgently send the Ifriqiyan army back to Africa.

Meanwhile, Ubayd Allah assembles a column of heavy cavalry, made up of the Arab aristocratic elite of Kairouan. He places the nobles under the command of Khalid ibn Abi Habib al-Fihri, and sends him to Tangier, to contain the Berber rebels, while awaiting Habib's return from Sicily. A smaller reserve army was placed under Abd al-Rahman ibn al-Mughira al-Abdari and tasked with holding Tlemcen, in case the Amazigh rebel army broke through the column and attempted to move towards Kairouan. . Maysara's Amazigh forces encountered Khalid ibn Abi Habib's Ifrqiyan vanguard column somewhere in the vicinity of Tangier. After a brief skirmish with the Arab column, Maysara abruptly orders the Amazigh armies to fall back towards Tangier. The Arab cavalry commander Khalid ibn Abi Habiba did not follow through, but simply held his line south of Tangier, blockading the Berber-held city, awaiting reinforcements from Habib's Sicilian expedition.

During this respite, the Amazigh rebels reorganized and undertook an internal coup. Berber tribal leaders quickly deposed (and executed) Maysara and elected Berber leader Zenati, Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati, as the new Amazigh "caliph". The reasons for Maysara's downfall remain obscure. Perhaps the sudden cowardice he showed in front of the column of Arab cavalry rendered him militarily unfit, perhaps because the Puritan Sufrite preachers found a flaw in his piety of character, or perhaps simply because the Zenata tribal leaders, being closer to the Ifriqiyan front line, felt it was up to them to lead the rebellion. The new Berber leader Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati chose to immediately attack the Ifriqiyan column in slow motion before it could be reinforced. Khalid ibn Hamid's Berber rebels crushed and annihilated Khalid ibn Abi Habiba's Arab cavalry in an encounter known as the Battle of the Nobles, due to the actual slaughter of the cream of Ifriqiyan Arab nobility. This battle is tentatively dated to around October-November 740.

The immediate Arab reaction to the disaster shows how unexpected this reversal was. At the first news of the nobles' defeat, Ibn al-Mughira's reserve army in Tlemcen panicked. Seeing Sufrite preachers all over the city, the Umayyad commander ordered his nervous Arab troops to carry out a series of roundups in Tlemcen, several of which ended in indiscriminate massacres. This caused a massive popular uprising in the hitherto quiet city. The city's predominantly Amazigh population quickly drove out the Umayyad troops. The front line of the Berber revolt has now jumped to the Middle Maghreb (Algeria).

Habib ibn Abi Obeida's Sicilian expeditionary army arrived too late to prevent the massacre of the nobles. Realizing that they were unable to confront the Amazigh army on their own, they retreated to Tlemcen, to gather the reserves, only to find that this city too was now in disarray. There Habib met Musa ibn Abi Khalid, an Umayyad captain who had bravely stayed behind in the vicinity of Tlemcen mustering whatever loyal forces he could find. The state of panic and confusion was such that Habib ibn Abi Obeida decided to blame the innocent captain for all the mess and cut off his hand and leg as punishment.

Habib ibn Abi Obeida entrenched what remained of the Ifriqiyan army in the vicinity of Tlemcen (perhaps as far as Tahert), and appealed to Kairouan for reinforcements. The request was forwarded to Damascus.

Caliph Hisham, hearing the shocking news, reportedly exclaimed:

“By God, I will most certainly rage against them with Arabian rage, and I will send against them an army whose beginning is where they are and whose end is where I am! »

The Battle of the Nobles

The Battle of the Nobles is an important confrontation of the Amazigh revolt around 740. It resulted in a major victory for the Berbers over the Arabs near Tangier. During the battle, many Arab aristocrats were massacred, leading to the conflict being called the " Battle of the Nobles ".

Maysara's Berber forces encountered the vanguard of Khalid ibn Abi Habib's Ifrqiyan column somewhere in the vicinity of Tangier. After a brief skirmish, Maysara ordered the Amazigh armies to fall back. Rather than pursue, the Arab cavalry commander Khalid ibn Abi Habib held the line just south of Tangier, blockading the Berber-held city while awaiting reinforcements from the Sicilian expedition.

Regrouping after these skirmishes, the Amazigh rebels deposed and killed their leader, Maysara al-Matghari, and elected the Zenati Berber leader, Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati, as their new Berber commander. The reasons for Maysara's downfall are not entirely clear - perhaps because his sudden cowardice in front of the Arab cavalry column rendered him militarily unfit, perhaps because the Sufrite Puritan preachers found fault in the piety of his character, or simply because the leaders of the Zenati tribe, being closer to the Ifriqiyan front line, felt that they were the ones who should lead the rebellion.

The chronicler Ibn Khaldun asserts that Khalid ibn Abi Obeida met the Amazigh forces and held his position at the "Shalif" river, which many commentators have mistaken for the famous Chelif river (Wadi ash-Shalif) in the center of Algeria. However, it is highly unlikely that the Berber rebel army was so far east at this time. Modern historians have suggested that Ibn Khaldun or his transcribers made a mistake here. Julien (1961: p. 30) [xxxii] suggests that Ibn Khaldun actually meant the Sebou River, the upper reaches of which would effectively place the Ifriqiyan column near Tangier. The chronicler an-Noweri indeed reports that the skirmish took place outside the walls of Tangier.

Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati chooses to immediately attack the Ifriqiyan army which is in the vicinity of ''Shalif'' (or the outskirts of Tangier) before the arrival of reinforcements from Sicily. The Amazigh rebels of Khalid ibn Hamid crushed and completely defeated the army of Khalid ibn Abi Habib, slaughtering the cream of the Ifriqiyan Arab nobility.

The news of the massacre of the Ifriqiyan nobles spreads like shock waves. Ibn al-Mughira's reserve army in Tlemcen was panicked. Seeing Sufrite preachers all over the city, the troops launch a series of indiscriminate massacres, causing a massive uprising in the hitherto quiet city.

Habib ibn Abi Obeida's Sicilian expeditionary army arrives too late to prevent the massacre of the nobles. Realizing they were in no position to confront the Amazighs alone, they retreated to Tlemcen to gather the reserves, only to find that this town too was now in disorder and the troops were killed or dispersed.

In February 741, the Umayyad Caliph Hisham appointed Kulthum ibn Iyad al-Qasi to replace the disgraced Obeid Allah as governor of Ifriqiya. Kulthum was to be accompanied by a fresh Arab army of 30,000 men, raised from Jund regiments from the east. The even more important Battle of Bagdoura will take place at the end of the year 741.

Battle of Bagdoura

The Battle of Bagdoura (or Baqdura) was a decisive clash in the Berber revolt at the end of the year 741. [xxxvi] It followed the Battle of the Nobles the previous year and ended in a major victory of the Amazighs over the Arabs near the Sebou River (near present-day Fez) in October 741. [xxxvii] The battle definitively broke the hold of the Umayyad Caliphate over the far west of the Maghreb (Morocco), and the retreat of the Syrian elite forces in Spain that resulted and impacted the stability of al-Andalus.

The "Syrian" Jund army (as it was called, despite its Egyptian contingent) left early in 742 and arrived in Ifriqiya in July–August. The vanguard Syrian cavalry, commanded by Balj ibn Bishr, which had outstripped the bulk of the forces, was the first to arrive at Kairouan. Their brief stay was not happy. The Syrians arrived in a haughty spirit, playing their part as saviors of the unfortunate Ifriqiyans. They received a cold reception from the wary Ifriqiyan authorities in Kairouan – the city gates were reportedly closed as they approached Balj, and local officials were not at all cooperative in responding to demands for the Syrian vanguard. Interpreting this as ingratitude, frustrated Syrians forced themselves into the city, requisitioning supplies and quartering troops in citizens' homes, regardless of local authorities or priorities.

The citizens of Kairouan immediately wrote to the Ifriqiyan military commander Habib ibn Abi Obeida (then with the rest of the Ifriqiyan army, still in the suburbs of Tlemcen) to complain about the behavior of the Syrians, and he sent a fiery missive to Kulthum threatening to turn its weapons against the Syrians if the abuses in Kairouan do not stop. Kulthum's diplomatic response calmed things down a bit.

Moving more slowly with the bulk of the forces, Kulthum ibn Iyad did not enter Kairouan himself, but merely dispatched a message entrusting the city government to Abd al-Rahman ibn Oqba al-Ghaffari, the qadi of 'Ifriqiya. Then, gathering the Syrian vanguard, Kulthum hurried to link up with Habib ibn Abi Obeida's remaining Ifriqiyan forces holding ground in the vicinity of Tlemcen.

The junction between the African and Syrian forces has not been smooth. The Ifriqiyans were still furious at the news of the Syrians' misconduct in Kairouan, and the Syrians still irritated by the ungrateful reception they had received. The tone rises when Balj ibn Bishr brings up Habib's threatening letter and asks Kulthum to immediately place the Ifriqiyan commander under arrest for treason. In turn, Habib ibn Abi Obeida threatened to leave the battlefield unless the insufferable Balj and the Syrian commanders apologized and treated the Ifriqiyans with more respect. The feud escalated and the armies nearly came to blows. By skillful diplomacy, Kulthum ibn Iyad succeeded in defusing the situation and keeping the armies together, but mutual resentments were to play a part in what followed.

Ancient pre-Islamic tribal rivalries also played a role, as the Ifriqiyan Arabs were largely of South Arabian ("Kalbid" or "Yemeni") tribal descent, while the Syrian Jund were descended from North Arabian (" Qaysid” or “Syrian”). Balj ibn Bishr, by general opinion, a Qaysid chauvinist, played on this difference.

The junction made, Kulthum ibn Iyad led the quivering Arab army (30,000 Syrians and some 40,000 Ifriqiyans) westward, and descended into the Sebou valley in central Morocco, where the Amazigh rebel army had been assembled. .

The Berber rebel army, under the leadership of Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati (possibly jointly with a certain Salim Abu Yusuf al-Azdi), some 200,000 strong, greatly outnumbered the Arabs. But the Amazighs were very poorly equipped, many carrying only stones and knives, with little or no armour, many wearing only a loincloth. But they compensated for this with their knowledge of the terrain, their familiarity with Arab weapons, their excellent morale (they had just defeated the cream of the Arab army the previous year) and, what should not be underestimated, a fanatical religious fervor of Sufrite inspiration. The Berbers had their heads shaved in the Sufrite Kharijite fashion and attached copies of the Koranic texts to the ends of their great spears and swords.

The Arab armies under the command of Kulthum ibn Iyad meet the Amazigh army of Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati at Bagdoura (or Baqdura), near the Sebou river, in the vicinity of present-day Fez.

Having already fought with and against Berbers, Habib ibn Abi Obeida and the other Ifriqiyan officers advised Governor Kulthum ibn Iyad against being impetuously. The army was not to be tempted to open battle, but rather to entrench itself and send in the cavalry only to harass. Habib strongly urged Kulthum to fight only " foot to foot and cavalry to cavalry ". But Balj ibn Bishr persuaded his uncle that the Berber populace could be easily defeated, and that they should move against them immediately.

Listening to his nephew, Kulthum ibn Iyad rejected the Ifriqiyen's advice, and the forces fell into attack formations. Balj was given command of the elite Syrian cavalry while Kulthum remained with the Syrian infantry. Habib ibn Abi Obeida and his Ifriqiyan troops were placed under Umayyad officers.

Certain that his superb cavalry could easily overcome the ragged Amazighs, Balj ibn Bishr was the first to set out. But the Berbers proved to be excellent slingers and skirmishers. They quickly ambushed many Syrians and put them out of harm's way (sometimes by throwing a sack full of stones at the horses' heads). To prevent the Arab infantry from intervening to support their incapacitated comrades, the Amazighs launched a stampede of wild mares (driven mad by water bags and leather straps tied to their tails) through the Arab ranks, sowing confusion. By these rudimentary means, the Arab forces were quickly deprived of much of their cavalry, their main advantage.

Gathering the rest of his cavalry, Balj charged furiously and directly at the Amazigh lines. But rather than hold the ground, the Berber forces move aside to open a corridor for the Syrian cavalry to pass, then close it, separating the cavalry from the Arab foot soldiers.

While the rear guard held a line to prevent the cavalry from returning, the bulk of the Berber army, using their numbers to their advantage, swooped down on the Arab infantry. The Ifriqiyan column was the first to be hit. Specially targeted, the main Ifriqiyan commanders, including Habib ibn Abi Obeida, were quickly killed. Seeing their officers downcast and not particularly keen to stay with the Syrians, the Ifriqiyan ranks broke up and retreated. Now alone, the Syrian infantry, with Kulthum at its head, resisted for a while longer, but the number of Amazighs soon overwhelmed them.

The Arabs are routed. Of the initial Arab troops, a third are said to have been killed, a third captured, and a third escaped. Another account put the casualties at 18,000 Syrians and some 20,000 Ifriqiyans. Among the dead are Governor Kulthum ibn Iyad al-Qasi and Ifriqiyan commander Habib ibn Abi Obeida al-Fihri.

The remaining Ifriqiyan forces fled in dispersed order towards Kairouan. The remaining Syrian troops (about 10,000 men), now under the leadership of Kulthum's nephew, cavalry commander Balj ibn Bishr, fled to the coast, with the Berbers in pursuit. The Syrians barricade themselves in Ceuta and ask to cross the water to reach Spain. The wary Andalusian ruler Abd al-Malik ibn Qatan al-Fihri initially refuses, but eventually relents and allows them to cross in early 742, an event that will have destabilizing repercussions for al-Andalus thereafter. .

We no longer hear of the Zenati Amazigh leader Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati who won the two great victories over the Arab armies. He disappears from the chronicles shortly after this battle. The Berber revolt will continue, however, under other commanders.

News of the Amazigh victory over the Arabs encouraged wider Berber rebellions throughout North Africa and Spain, and even larger Berber armies were mustered by two more commanders, Oqasha ibn Ayub al-Fezari and Abd al -Wahid ibn Yazid al-Hawwari, against Kairouan itself. But Egyptian governor Handhala ibn Safwan al-Kalbi's quick reaction prevented them from taking the city. The Berber armies of Ifriqiya were destroyed by Handhala in 742 in two massively bloody battles at El-Qarn and El-Asnam

Nevertheless, the Battle of Bagdoura proved decisive. It definitively broke the Arab hold on the Greater Maghreb (Morocco and western Algeria). These regions are devolved to the local Amazigh rulers and will never be recovered by the Eastern Caliphate. This is the first major territorial loss of the Islamic Caliphate, the first Muslim provinces to break away and chart an independent course.

The Sufrite Threat

The most immediate threat appeared in southern Ifriqiya, where the Sufrite leader Oqasha ibn Ayub al-Fezari immediately raised a Berber army and laid siege to Gabès and Gafsa. By a quick southward foray with the rest of the Ifriqiyan army, the qadi of Kairouan Abd al-Rahman ibn Oqba al-Ghaffari succeeded in defeating and dispersing the forces of Oqasha near Gafsa in December 741. But the qadi possessed very few Arab troops to engage in pursuit, and Oqasha immediately set about gathering his forces quietly around Tobna in the Zab valley of western Ifriqiya.

Immediately upon learning of the Bagdoura disaster, Caliph Hisham ordered Handhala ibn Safwan al-Kalbi, the Umayyad governor of Egypt, to quickly take charge of Ifriqiya. In February 742, Handhala ibn Safwan rushed his army west and reached Kairouan around April 742, just as Oqasha was returning to try his luck. Handhala's forces push Oqasha back again.

As Oqasha again gathered his forces in the Zab, he encountered a large Amazigh army coming from the west, under the command of the Berber leader of the Hawwara, Abd al-Wahid ibn Yazid al-Hawwari (possibly sent by the Amazigh Caliph Khalid ibn Hamid az-Zanati, although he is not mentioned in the chronicles). Abd al-Wahid's army consisted of some 300,000 Amazihs, apparently the largest Berber army ever seen. After a quick consultation, Oqasha and Abd al-Wahid agreed on a joint attack on Kairouan, with Oqasha leading his forces along a road to the south, while Abd al-Wahid led his large army through the northern passes. They would meet in the Tunisian plains, before Kairouan.

Hearing of the approach of the great Berber armies, Handhala ibn Safwan understood that it was essential to prevent their joining. Deploying a force of cavalry to harass and slow Abd al-Wahid, Handhala threw the bulk of his forces south, overwhelming Oqasha in a bloody battle at El-Qarn[xliv] and taking him prisoner. But Handhala had himself suffered heavy casualties and now had to face the unfortunate prospect of Abd al-Wahid's gigantic army. Quickly retracing his steps, Handhala would have put the entire population of Kairouan under arms to reinforce his ranks, before setting out again. In the bloodiest encounter of the Berber wars, Handhala ibn Safwan defeated the large Berber army of Abd al-Wahid ibn Yazid at El-Asnam around May 742 (possibly a little later), three kilometers from Kairouan . Some 120,000 to 180,000 Berbers, including Abd al-Wahid, fell on the battlefield in this encounter alone. Oqasha was executed soon after.

Although Kairouan had been saved for the caliphate, and with it Ifriqiya, Handhala ibn Safwan now had the unenviable task of bringing home the more western provinces still under Amazigh sway. He will not have the opportunity to achieve this.

You can see the second part: The Great Amazigh Revolution-2-

https://fr.akalpress.com/6230-la-grande-revolte-amazighe/