It may be the key to one of the mysteries of evolution.. fossils that are 500 million years old

A number of researchers have discovered several fossils of creatures that lived in the Cambrian period that had what may be the first skeleton of creatures that lived on Earth. These fossils could be the first nucleus of today's organisms with complex skeletons.

Researchers say Gangtoconia aspira had pink soft tissues similar to what is found in some current jellyfish species.

A group of exceptionally well-preserved fossils unearthed in China's eastern Yunnan province has enabled scientists to solve a centuries-old mystery related to the evolution of life on Earth.

Scientists say that the fossils revealed what the first animals whose ancestors later obtained developed skeletons looked like.

The fossils show types of the first animals that enjoyed primitive but solid and strong skeletons about 550-520 million years ago during the Cambrian period, or the so-called Cambrian Explosion.

Among the Cambrian rocks in the Chinese province, the research team found well-preserved tube fossils that can be identified as a type of marine worm and unique legged worm, closely related to the arthropods and annelids that live on planet Earth today.

Many of these early fossils are simple hollow tubes ranging in length from a few millimeters to several centimeters. The type of animal that made these skeletons was unknown to scientists at first, because they lacked the soft parts needed to identify and categorize them into major groups of animals still alive today.

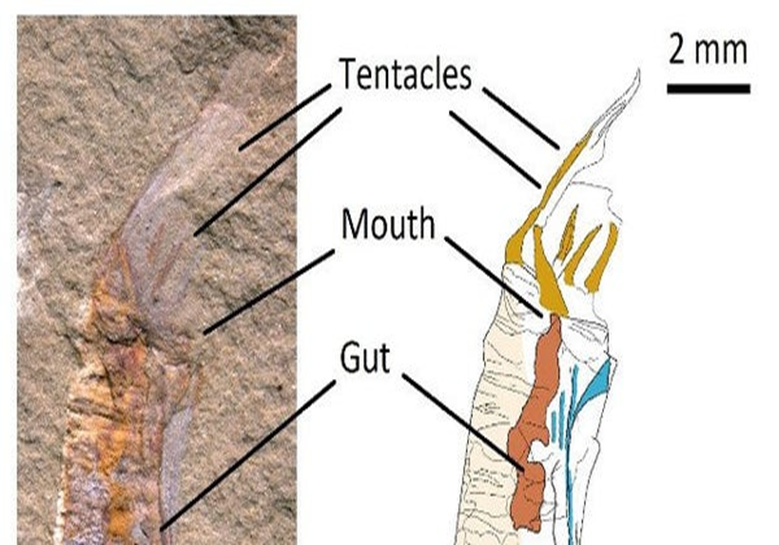

The new group, which is about 514 million years old, includes four samples of organisms called Gangtoucunia aspera with soft tissues that are still intact, including the intestines and mouth parts, according to the website "Fays.org".

These fossils reveal that this species had a mouth surrounded by a ring of smooth claws about 5 mm long. It is possible that these claws were used to sting and capture prey, such as small marine arthropods. Fossils also show that these organisms had blind intestines (open at one end only), divided into internal cavities, which filled the length of the tube.

The results of the study were published inProceedings of the Royal Society B.

Scientists say that these Gangtoconia traits are only found today in jellyfish, anemones and their relatives, organisms whose soft parts rarely appear in the fossil record. The study shows that these simple animals were among the first to build solid skeletons that make up much of the known fossil record.

According to the researchers, Gangtoconia (if it survived) would have looked similar to a polyp of scyphozoan jellyfish, with a rigid tubular structure.

Unlike the adenoids of live jellyfish, the tubes of gangtoconia are made of calcium phosphate, a hard compound that makes up teeth and bones, and the use of this material to build skeletons has become increasingly rare among animals over the ages.

Dr Luke Barry of the University of Oxford's Department of Earth Sciences and corresponding author of the study said: 'This is an extremely rare find. These mysterious tubes are often found in groups of hundreds of individuals, but so far they have been considered problematic fossils, because we had no way of classifying them. Thanks to these With the unusual new specimens, an essential piece of the evolutionary puzzle has been put into place."

The new specimens clearly show that Gangtoconia was not related to annelids (eg earthworms, polychaete worms and their relatives) which was previously suggested for similar fossils. It is now clear that Gangtoconia had a smooth exterior and longitudinally divided intestines, while the annular organisms had segmented bodies with a transverse division of the body.

The fossil was found at a site in the Gulufang Division of Kunming, eastern Yunnan Province, China. Anaerobic (or oxygen-poor) conditions limit the presence of bacteria that normally degrade the soft tissues of the fossils, causing the fossils to best retain the shape of the original organism.

"The first time I discovered the pink soft tissue on top of the Gangtokunya tube, I was puzzled," said Guanxhu Wang, a doctoral student who collected and discovered the samples. "The next month, I found three more samples that were holding the soft tissue, which was very exciting and made me rethink about the nature of this being.

"The soft tissues of Gangtoconia - in particular the tentacles - reveal that it is certainly not a worm as previous studies have suggested, but more like a coral reef."

Although the fossil clearly shows that Gangtoconia was more like a primitive jellyfish, this does not exclude the possibility that other types of early tubular fossils looked very different.

Source :Websites