They are 514 million years old. Fossils that do not belong to any living organism baffle scientists

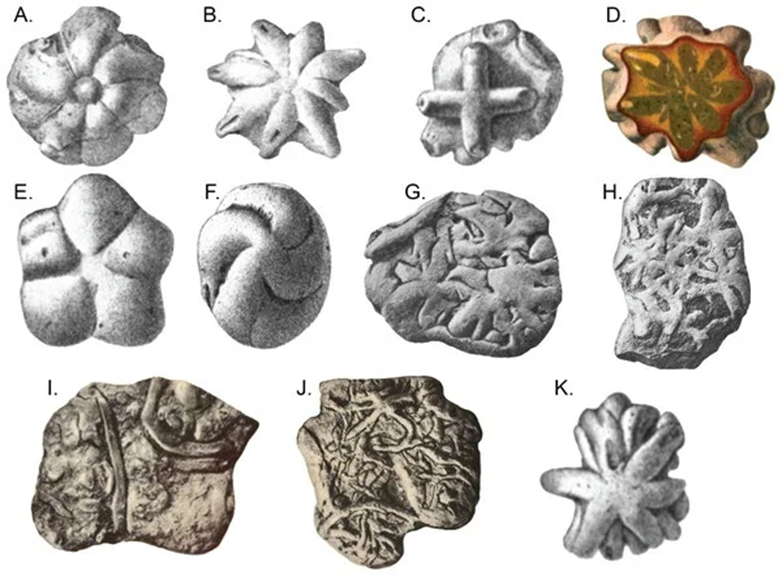

Three-dimensional star-shaped fossils, 514 million years old, have baffled scientists after they were discovered more than 100 years ago.

The strange fossils were found in 500 million-year-old bedrock in the southwestern United States in 1896.

At the time, paleontologists assumed that these were the remains of ancient tentacled jellyfish, a lineage of animals dating back at least 890 million years. They called it Brooksella alternate.

These strange structures of Brooksella alternate have suffered an identity crisis ever since they got their name, as for decades, scientists have argued that they are the remains of burrowing worms, swollen algae, or glass sponges.

Meanwhile, others were not convinced that these structures were fossils, and instead explained them as gas bubbles.

In 1896, scientist Charles Doolittle Walcott was tasked with examining mysterious star-shaped fossils found in the Conasauga Formation in the southeastern United States. Walcott initially described the fossilized specimens as jellyfish with tentacles. However, he also considered that they could be hexapod sponges, despite the fact that he did not discover traces of the spicules that form part of the skeleton of these marine animals.

Since that date, the taxonomic identity of Brooksella alternate has been reassessed on multiple occasions.

Now, a new look at Brooksella alternate using high-resolution 3D imaging and chemical analysis suggests that these structures are, in fact, a “pseudofossil.”

According to the authors of the new study, Brooksella is not a sponge, but an unusual form of silica. This natural mineral particle can fuse to form spherical, cubic or hexagonal shapes.

What looks like a Brooksella "mouth" is actually directed downward toward the sediment, making it very difficult to filter food from the water as a sponge does.

The downward-facing "mouth" might make us think of a starfish, but the ancestor of all sea stars is thought to have appeared on Earth only 480 million years ago, tens of millions of years after the Brooksella fossil was dated.

Hidden worms do not seem to be a satisfactory explanation either. While these organisms existed on Earth during the mid-Cambrian period, scientists have found no sign that they made star-shaped structures.

The only explanation that made sense came when experts compared Brooksella to other concrete forms of silica produced by Cambrian bedrock around the world.

“We found no difference between Brooksella and concrete, other than that Brooksella had lobes that were not present in concrete,” the team wrote. Thus we concluded that Brooksella was not part of the early diversification of sponges in the Middle Cambrian seas, but was an unusual type of silica cement. “The formations can be all kinds of shapes, to the point that some appear to have formed organically.”

“I was interested in the Brooksella skeleton because, unlike most fossils, it had a three-dimensional shape like a puffy, star-shaped dough that is unusual for spongy animals like sponges,” explains paleontologist Sally Walker of the University of Georgia.

In this new investigation, Brooksella was ruled out to be of biological origin, after subjecting it to chemical analysis along with high-resolution 3D images obtained by micro-computed tomography (micro-CT).

But this does not mean that scientists have solved all of Brooksella's mysteries. It remains unclear, for example, why so many strange concretes with the same shape have been found in this one region of the world.

These objects look quite similar on the outside, but when scientists examined their internal dynamics using micro-scanning, they found that they are all quite different in nature. More research will be needed to find out how it actually formed.

“While microCT's applications are nearly endless in materials science and engineering fields, its ability to elucidate the fossil record is just beginning,” says geoscientist James Schiffbauer of the University of Missouri. “This project is an excellent example of the types of fossil mysteries we can solve using microCT applications.”

Source : websites