Spain: Mérida, the mysterious Roman city

This Roman theater is just one of the many ancient monuments that the Spanish city of Mérida inherited from the ancient city of Augusta Emerita. This little tourist town of Extremadura also has aqueducts, houses and refined mosaics.

Mérida, a little-known city in Extremadura, contains so many treasures that the skeletons of looters have been found among its ruins.

At its height in the first century CE, the Roman Empire spanned three continents, from the United Kingdom to Egypt and from Syria to Portugal . Of the more than 600 sites listed by archaeologists, few offer such a comprehensive overview of life under the Roman Empire as the remains of Augusta Emerita, in present-day Mérida, Spain .

This site in the southwest of the country, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site , is located in the autonomous community of Extremadura, a predominantly rural region known above all for its dry summers, its arid culture and its pata negra. Mérida, which is rarely mentioned when mentioning Rome or Pompeii, makes up for its lack of notoriety by the scale of its Roman structures. On 30 hectares, the modern city shelters all the characteristic elements of an ancient metropolis: hydraulic works, bridges, forum, theatre, amphitheater, circus, houses and necropolises.

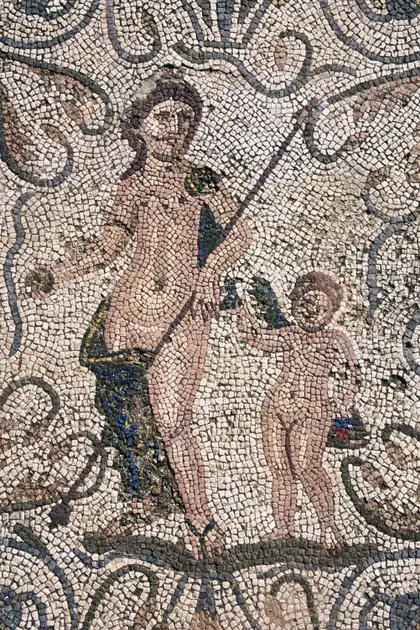

At the National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida, Spain, the wall and floor mosaics depict hunting scenes and were taken from nearby houses.

"Nowadays, Mérida is a classical archeology lab," says Trinidad Nogales Basarrate, director of the city's National Museum of Roman Art . Thanks to the impressive restoration of the largest house in the ancient city carried out in 2020, and thanks to the particular attention paid to the balance between tourism and heritage preservation, visitors have good reasons to go and discover one of the oldest cities of Spain.

RISE AND FALL OF A ROMAN CAPITAL

Augusta Emerita was founded in 25 BC. AD by the Emperor Augustus as a colony for soldiers ( emeriti ) who were sent back to civilian life during the Cantabrian Wars . The city was ideally placed near the Guadiana river, in a valley between steep forests and fields of holm oaks (whose bark has long been used to produce cork). Augustus made Mérida the capital of Lusitania, a region straddling the current border between Portugal and Spain.

It also became the home of the imperial cult which worshiped emperors as gods. Among the traces left by this cult, we found in particular a veiled bust bearing the effigy of Augustus, represented as Pontifex Maximus, which is exhibited in the museum of Mérida, but also a temple of Diana in the center of the city. The latter (probably erected during the reign of Augustus) is actually a temple of the imperial cult rising from a large granite podium and whose tympanum points towards the sky.

At its height, in the first and second centuries, 40,000 people lived in Mérida and some even came from Asia Minor. The city remained a strategic stronghold and administrative capital until the Moorish occupation came in the eighth century. But when the reconquista ended in the 12th century , the city had long since been a footnote on the scrolls of history. Many of its “immoral” structures had been filled in to make way for farms and new buildings.

The dining room of the house of the amphitheater houses a mosaic in a good state of conservation representing Venus and Cupid.

There are many other Roman sites outside Italy (in Portugal, Morocco , France, etc. ) “You can find an amphitheater, baths or an aqueduct there,” comments Marco Mangut, tourist guide for the Extremadura. “But discovering a theatre, an amphitheater and a circus – that is to say the three main entertainment structures – is extremely rare outside of Rome. »

ANTIQUITY AND MODERNITY MEET

The remarkable ancient structures of Mérida, which is in the least populated and less touristy region of Spain, have been relatively easy to unearth. “If you go to Rome, the difference between the current ground level and the old one is about 10 meters. In Mérida, it's half as much, and more. You could come across Roman ruins when digging a trench to run a fiber optic cable,” says Jonathan Edmondson, professor of Roman history and classical humanities at the University of York in Toronto and co-author of Si muero , no me olvides ("If I die, don't forget me") , which examines the social life of Augusta Emerita by focusing on the epitaphs that have been discovered there.

Inside the modern city, visitors will come across some thirty monuments (of Roman and Christian influence) administered by the Heritage Consortium of the City of Mérida . Thanks to regular archaeological excavations and preservation projects, there is always something new to discover.

On the cosmological mosaic of the house of the mithraeum one can see mythological figures representing the Earth and the sky.

The recently reopened amphitheater house , which is the largest dwelling dating from antiquity in the city, gives an idea of the way of life of the wealthy Romans. A brand new 370 square meter steel walkway winds just above the house whose hallways and living areas are visible through transparent slabs. The project also made it possible to install a roof to protect the house from the merciless sun of Extremadura.

"The amphitheater house represents one of the most distinctive examples of the peri-urban Roman dwellings that dotted the landscape on the outskirts of the Augusta Emerita enclosure," says Raquel Nodar Becerra, who oversaw the building's restoration in partnership with the architect María López.

The largest dwelling in the city, the amphitheater house houses more than 650 square meters of faded-color mosaics depicting gods, nature and everyday life. Those that are best preserved adorn the floor of the dining room. Venus and Cupid are staged there within lush vegetation, and a male trio tramples grapes while small birds peck in the vines.

These mosaics are not only decorative; they tell us more about the people who lived there and their way of life, a bit like an Architectural Digest issue. In the house of the mithraeum, 800 meters from the house of the amphitheater, the cosmological mosaic features mythological figures and depicts the celestial, terrestrial and marine kingdoms as well as their elements such as wind and water. "This suggests that the owner of the house had fairly deep intellectual interests", analyzes Jonathan Edmondson.

At the Alcazaba, a 9th century Moorish fortress , you can admire Roman mosaics.

The theater and the amphitheaterRomans form the second side of a "triangle" with the house of the amphitheater and are also very well preserved. The stone benches of the amphitheater, some of which have suffered erosion, encircle an arena where the gladiators clashed. The theater has a columned proscenium once decorated with sculptures as well as a three-tiered seating system corresponding to the city's different social classes. Marco Mangut says these columns were so coveted that in the 1990s archaeologists unearthed the skeletons of fifth-century looters with their hands clinging to ropes tied around their loot. By pulling on the columns to bring them down, these looters caused the roof to collapse and found themselves trapped.

The third side of the triangle is formed by the National Museum of Roman Art , which houses under its classically inspired vaults exhibitions on Roman culture as well as some 3,000 artefacts (out of a collection of 50,000). Among these we find glass, coins but also a large stone medallion with the effigy of Medusa.

Not far from there, the gigantic circus welcomed up to 30,000 spectators for processions and chariot races in which Diocles took part. Throughout his career, which lasted twenty years, this charioteer amassed the equivalent of 13.3 billion euros. He is the highest paid athlete of all time .

Near the circus are three of the four aqueducts that carried water from the surrounding springs and reservoirs to supply the entire city. The Aqueduct of Miracles , 25 meters high, is the best preserved. Its graceful ashlar, brick and concrete arches stretch for more than half a kilometer.

The Roman bridge of Mérida crosses a meander of the Guadiana. For a memorable photo, head to the top of the Alcazaba , a ninth-century Moorish fortress. You can see this centuries-old bridge juxtaposed with the much more recent Lusitania bridge, designed by the architect Santiago Calatrava

Next to the Alcazaba, nestled between the residential buildings of Paseo de Roma, is the Archaeological Zone of Morerías . The largest stretch of Roman wall in the city is preserved there, and there is an urban sprawl including houses and streets.

PRESERVING THE PAST, PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE

Nowadays, the main objectives (and challenges) for Mérida are to make sustainable use of these ancient spaces but also to preserve and study them. The Roman Theater hosts, for example, the International Classical Theater Festival , where famous Spanish actors stage plays from ancient Greece and Rome. The amphitheater serves as the backdrop for the ceremonies of Holy Week. On the occasion of Emerita Lvdica , a historical re-enactment on steroids which takes place in the fall, actors from the region and local residents dress in Roman costumes and re-enact scenes of daily life (gladiator clashes, funerals, sale of objects and food in markets…)

This type of event, like day-to-day tourism, generates funding for the preservation of heritage while leading to the erosion of monuments (this is a frequent vicious circle in the world of conservation which does not only concern Mérida) . Environmental damage is also a source of concern. Extreme weather events, the growth of biofilms and lichen are all phenomena likely to degrade the stone.

Moreover, an ancient city still sleeps under the modern city. Whenever construction of a building is undertaken in Mérida, the archaeologists of the Consortium are present to document the potential discovery of ruins. The goal is to create an interactive map of the city that allows visitors to click on a building or a street to discover its Roman past.

Once identified, ancient structures are sometimes integrated into urban life. This is for example the case of two buildings whose basements shelter, behind glass walls, their old foundations. Other discoveries, in particular a Roman mosaic unearthed during road works, found themselves covered again. It is a vivid illustration of the relentless march of time and the human desire for memory.

The inhabitants of Mérida accept this without flinching. “We understand that the city must move forward, concedes Marco Mangut. Even if we would like everything to be visible forever, it is impossible. It's really amazing to have such a lively city, where you make new discoveries every year. We try to make the preservation of Roman heritage and new life coexist. »

Source : websites