Removing extra chromosomes in cancer cells prevents the growth of malignant tumors

Many cancer cells contain too many chromosomes that play a role in promoting cancer. Tumor growth in cancer cells can be inhibited by eliminating the extra chromosomes, according to a recent study. Researchers have found that these extra chromosomes play a vital role in supporting the growth of tumors, so targeting and removing them can prevent tumors from forming. This discovery provides a promising new approach to treat cancer by selectively eliminating these abnormal chromosomes.

The mystery of the extra chromosomes

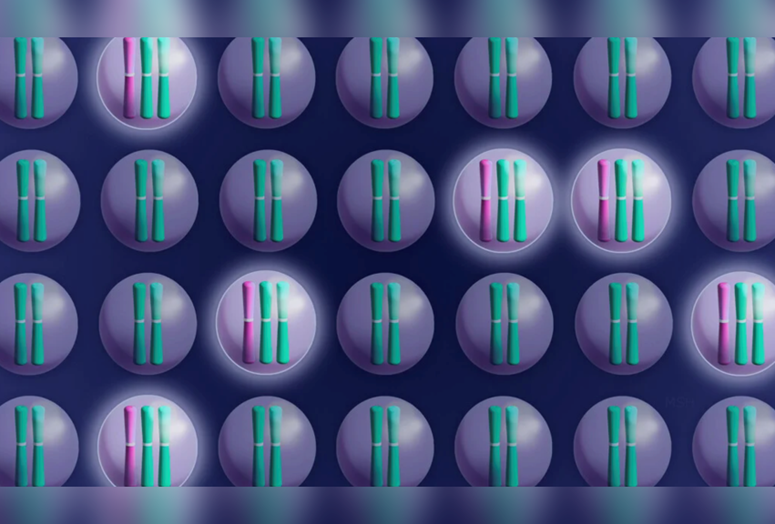

The role of extra chromosomes in cancer has long been a mystery with uncertainty as to whether they cause cancer or are a consequence of it. However, a recent study published in the journal "Science" on July 6, 2023, led by Jason Sheltzer, Assistant Professor of Surgery at Yale University School of Medicine in the United States, sheds light on this question by using a gene engineering technique known as CRISPR to edit and cut genes - which is one of the genetic engineering techniques in molecular biology through which the genomes of living organisms can be modified.

In the study, the researchers developed a new approach to remove entire chromosomes from cancer cells and succeeded in targeting aneuploidy, caused by an abnormal number of chromosomes in the aneuploidy cell, in three types of cancer: melanoma, stomach, and ovary using their innovative method called Disomy in Aneuploid cells CRISPR Restoring Targeting (ReDACT).

CRISPR gene editing and cutting technology

New approach to remove entire chromosomes from cancer cells, in three types of cancer: melanoma, stomach cancer and ovarian cancer

The study focused specifically on removing an abnormal third copy of the extended portion (the q arm) of chromosome 1 that is frequently seen in various cancers associated with disease progression, and often occurs early in cancer development. Remarkably, eradicating aneuploidy from the genomes of these cancer cells using restoring perturbations in the cells significantly compromised their malignancy and loss of tumorigenic ability.

"Dysfunctional addiction"

Based on these results, the researchers put forward the concept of "aneuploidy addiction" in cancer cells, compared to the previous discovery of "oncogene addiction", which indicates that the elimination of oncogenes disrupts the capabilities of tumor formation.

When they studied the role of an extra copy of chromosome q1 in promoting cancer, they found that genes overrepresented on three chromosomes instead of the typical two stimulated the growth of cancer cells. This gene overexpression revealed a vulnerability that could be targeted in aneuploid cancers. Using CRISPR again, the scientists showed that other types of aneuploidy were also present. Cancer cells with extra arms of chromosomes 7 or 8 gained increased growth as well.

However, aneuploidy of chromosome 1 provided a greater benefit and the cancer cells were "addicted" to this change, which was necessary for rapid growth. This addiction to aneuploidy may be a weak point, as the larger arm of the chromosome carries one gene whose protein can activate certain drugs, and aneuploid cells have a third copy of the gene so they must generate more active cells.

Experimental drugs

When the researchers tested two of the drugs on cancer cells, they found that the molecules killed a greater percentage of cells that were aneuploid on the long arm of chromosome 1. One of these drugs is now being used in clinical trials as a treatment for cancer. It would work best for patients who have aneuploidy of chromosome 1 in their tumors, the researchers say.

On the other hand, cancer biologist and pathologist Jinsong Liu of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in the US warns that aneuploidy is just one of the genome mix-ups in cancer cells and adds that cancer cells often acquire entire sets of chromosomes, not just individual chromosomes, resulting in abnormal numbers of all 23 chromosomes. He adds that researchers have "missed something fundamental" by focusing on aneuploidy, and that targeting aneuploidy may not be effective given the many genetic changes in cancer cells.

Source : websites