Discovery of an unknown language on a clay tablet

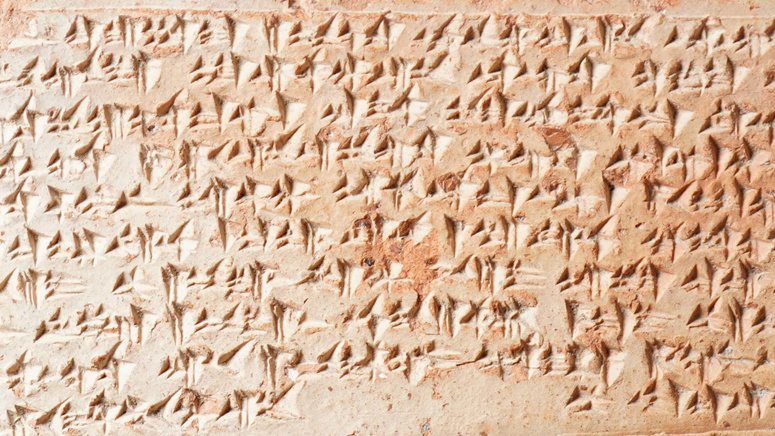

Copy of a clay tablet inscribed with a cuneiform language found on the Hattusa site, similar to the one recently discovered.

A clay tablet was discovered in the town of Hattusa, which is full of similar pieces. However, it has a small peculiarity: an entire passage is written in an unknown language.

The ancient city of Hattusa, located near the village of Boğazkale, in the province of Çorum, in present-day Turkey, was the ancient capital of the Hittite world, a now extinct civilization of central Anatolia, which dominated the high Turkish plateaus from the 19th to 12th centuries BCE.

Since its discovery in 1834 by the French archaeologist Charles-Marie Texier, generations of researchers have followed one another since the end of the 19th century, unearthing during excavations more than 30,000 tablets and fragments of clay tablets, inscribed in 2001 as UNESCO's “memory of the world”.

Since 2006, a vast excavation program led by Andreas Schachner, researcher at the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), has taken over and is working to study, among other things, these clay tablets which are full of information, ranging from from religious customs to medical practices, or even major passages in the history of the Hittite empire.

In August 2023, researchers made an astonishing discovery: a clay tablet different from the others. This tablet includes two passages. The first is in Hittite, easily decipherable by Daniel Schwemer, orientalist at the University of Würzburg. But the second is a quote in an incomprehensible dialect. Researchers believe they have discovered a previously unknown ancient language.

AN UNKNOWN CUNEIFORM WRITING

The Hattusa site is one of the largest in the region, for the second half of the Bronze Age. The newly unearthed tablet was found in an area where excavations began last year on the northwest slope of the city, where there is a large rock mound, which rises 400 meters above The valley.

“This tablet is different from those found this year,” explains Andreas Schachner. Indeed, the tablets or fragments found are generally released by erosion. They break away from their original site before tumbling into the valleys below. It is from these areas that archaeologists have collected the majority of clay tablets to date. In the case of the recent discovery, “we find by stratigraphy [on the northwest site] layers of monuments one on top of the other,” explains the chief archaeologist.

Aerial view where the tablet with inscriptions of an unknown language was discovered.

Below, there is a Hittite building, above which there is a building dating from the Iron Age, then another from the Byzantine Empire. “This tablet emerged while we were clearing parts of the Iron Age building, and we were on the Hittite building.” The Hittite origin of the tablet was also confirmed by the content of the text, which is particularly well preserved.

“This tablet is easily decipherable,” explains Daniel Schwemer. “It is written in a cuneiform style that Hittite scribes used in the 13th century BCE.” He adds that the beginning of the text is quite ordinary. This is one of the many ritual texts, where the author explains the progress of a sacrificial ceremony intended for the gods.

It is about the second part of the tablet that scientists are wondering. The scribe cited a kind of incantation, probably pronounced during the prayers which accompanied the sacrifice for the deity or deities venerated. “This recitation can be read as easily as the first passage,” notes Schwemer, “because cuneiform writing corresponds to a phonetic reading.” It is therefore possible to pronounce the sounds, “but I did not understand a single word of this recitation,” he admits.

After further study, researchers discovered that this language was neither Hittite nor any other dialect used, to their knowledge, in Hittite worship. So what language is it?

Despite the solicitation of linguist experts in Indo-European languages of ancient Anatolia, the mystery remains unsolved. However, a hypothesis emerges. “The language presents formulations and calligraphies that are particularly similar to what we know from certain forms of Louw,” explains Daniel Schwemer. Luwite is an Anatolian language related to Hittite-Nesite which would have been spoken in the mythical vanished city of Troy. In addition, the scribe mentions a language that was spoken in the country of Kalašma, which according to archaeologists must have been somewhere northwest of the court of the Hittite empire.

To date, this is the only known copy bearing inscriptions in this language. It sheds new light on the relationship of the Hittites with the northwestern regions of their empire. Until then, there was no evidence of this Hittite influence in the region.

AN EMPIRE AT THE CROSSROAD OF LANGUAGES AND CULTURES

The Hattusa tablets were written in cuneiform script by a very active imperial bureaucracy. These texts have stood the test of time, potentially thanks to accidental or criminal fires, which would have solidified them. The scribes only dried their writings in the sun, and without firing the clay with a flame these tablets would have been transformed into mud over time, according to Andreas Schachner. In addition to information relating to the cultural influences of the Hittite empire, including its languages, its rites and divinities, these artifacts also tell us about its political system and the mode of governance in this mountainous region of Anatolia.

Left: The Lions' Gate of Hattusa, located southwest of the ancient capital of the Hittite empire, a now extinct civilization that lived in present-day Turkey, around 1750 to 1200 BCE (photograph taken in August 2019 ).

The scribe who wrote this tablet in the Kalašma language recorded the instructions and recitations of a ritual observed in this region. “It is also possible that no one in the Kalašma region has ever written down the steps of this ritual,” specifies Daniel Schwemer. By writing about the customs and beliefs of the confines of the empire, the latter was nourished by an incredible linguistic and cultural diversity.

The capital Hattusa was a multilingual and multicultural crossroads, the center of the legitimacy of the sovereign's power. He had at his service an army of scribes very active in the field of “the administration of religious worship”, which explains the high concentration of clay tablets found on the site. “The king thus gained the favor of the gods, guaranteeing his ability to ensure the prosperity of his empire under his reign,” explains Daniel Schwemer.

“What is special about the discoveries of texts in the Hittite capital,” says Daniel Schwemer, “is that there is not a single text in a single language”, although all are written in cuneiform script. . Archaeologists have found influences from Mesopotamia, but also from Syria, with texts written in Akkadian.

The Hittite Empire, one of the four most powerful empires in West Asia in the 13th century BCE, did not impose a single language or religious tradition across the empire, at least not by force. The diversity of traditions in central Anatolia, reflected in texts written in the capital, shows that from a Hittite perspective, "it was probably about persuading people to believe in their system," says Andreas Schachner.

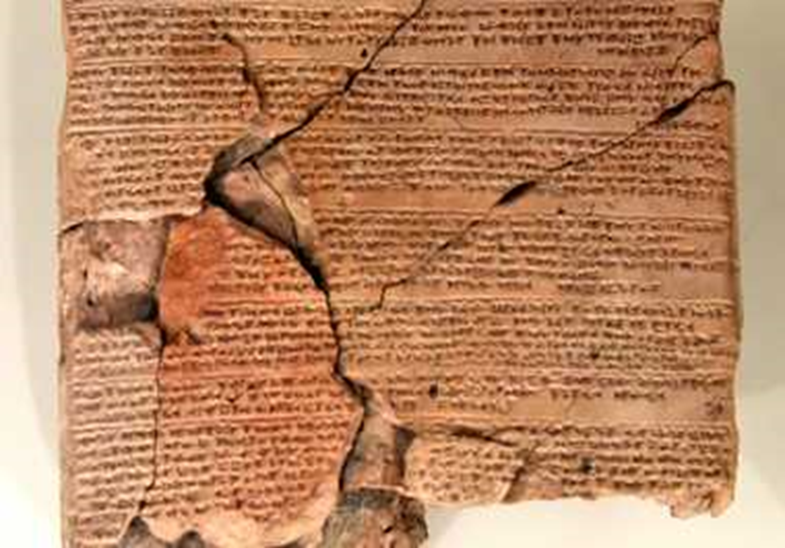

Right: Example of a clay tablet with cuneiform inscriptions. This tablet recounts the establishment of an Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty by Pharaoh Ramesses II (at Thebes) and King Ḫattušili III of Hattusa, in the mid-13th century BCE.

Hittite kings exercised their influence and power by seeking to integrate the religious traditions of different areas. “The Hittites also call themselves a people ‘of a thousand gods’,” concludes Andreas Schachner. “They thus chose to integrate all of the Anatolian beliefs into a single system, the thousand gods of Hatti.”

Source: websites