Kalašma, a language forgotten for 3,000 years, resurfaces from the ruins of the Hittite empire in Turkey

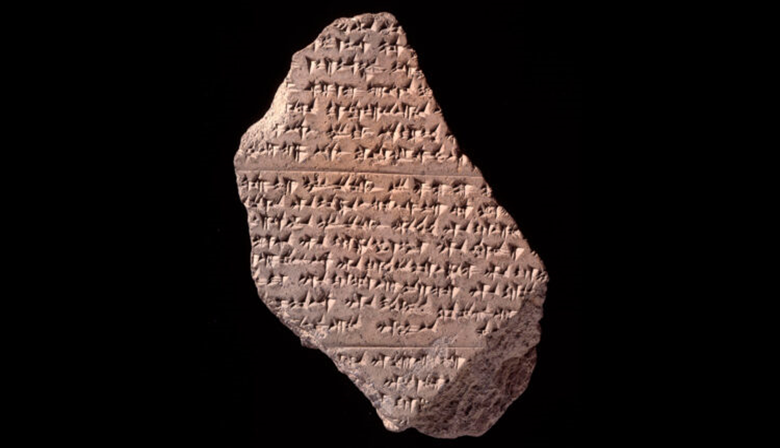

Nearly 30,000 clay tablets covered with cuneiform writing were discovered in Boğazköy-Hattuşa. Most are written in Hittite.

The recent archaeological discovery in Turkey, shedding light on the Kalašma language, rewrites the history of Bronze Age Anatolia. From the Boğazköy-Hattuşa excavations, it reveals a complex cultural and linguistic coexistence within the Hittite empire. It highlights the importance of cultural integration in the stability of the empire and enriches our understanding of the historical and linguistic dynamics of the period.

In the heart of Anatolia, archaeological excavations at Boğazköy-Hattuşa, a historic site of the ancient Hittite empire and listed by UNESCO, recently revealed an exceptional discovery: a clay tablet inscribed in a previously unknown language , called “Kalašma”. This find, among thousands of other tablets written in cuneiform, made during an expedition led by Andreas Schachner, archaeologist at the German Archaeological Institute, dates back more than 3,000 years. It offers new insight into the linguistic and cultural diversity of the Late Bronze Age. Relayed by a press release from the University of Würzburg, the revelation raises fascinating questions about assimilation practices and the coexistence of peoples within the Hittite empire, renowned for its tolerance and openness to foreign cultures.

An exceptional written heritage in the Hittite ruins

The recent archaeological discovery in Boğazköy-Hattuşa, Turkey, revealed a tablet more than 3000 years old. Boğazköy-Hattuşa was the capital of the Hittite Empire from around 1600 until around 1200 BCE. It is an archaeological treasure that continues to reveal secrets buried for millennia. Annual excavations at this site have unearthed nearly 30,000 cuneiform tablets. They provide valuable insight into the daily life, politics, economics and religious beliefs of the Hittite civilization.

Excavation site, at Boğazköy-Hattuşa.

These tablets, mainly written in Hittite, bear witness to the linguistic and cultural richness of the empire. Hittite, recognized as the oldest attested Indo-European language, was the lingua franca of the empire. It was used for official documentation, international treaties and religious texts. But some tablets contain words from other languages, including a previously unknown language.

The clay tablet was one of several sent to Germany for analysis by Daniel Schwemer, a professor at the University of Würzburg. From the Hittite introduction of the latter, he identified the language of Kalašma. It is a region located on the northwest edge of the Hittite heartland, near the modern Turkish city of Bolu.

The Lions Gate of Hattusa, the capital of the Hittite Empire.

The tablet in question stands out not only for its age, but also for its unique content. The presence of this new language suggests much more diverse cultural and linguistic interactions within the Hittite empire. This discovery questions the people speaking this language, their relationships with the Hittites and the impact of these interactions on the cultural dynamics of the region.

The “re” discovery of a forgotten language, Kalašma

The complex analysis of the Kalašma language involves an international collaboration of linguists and specialists in ancient languages. The first crucial step in identifying this language was the analysis of the tablet's introduction, written in Hittite. This introduction served as a key to unlock the rest of the text, thus revealing the presence of Kalašma's language.

The method of analysis combined traditional epigraphic techniques with modern linguistic approaches. The researchers first transcribed the text into Latin characters, a process requiring a deep understanding of ancient writing systems. Once this transcription was completed, the team began to analyze the linguistic structure of the text. They focused on syntax, vocabulary and morphology.

Researchers were able to identify similarities between the Kalašma language and other Indo-European languages, notably Luwian. These similarities relate to word endings, sentence construction and verb conjugation. However, despite these similarities, the Kalašma language has distinct characteristics. It is a previously unknown branch of the Anatolian Indo-European language family.

Historical and cultural implications of the Kalašma language

The discovery of the Kalašma language in the ancient Hittite empire opens a window on the linguistic and cultural diversity of Anatolia in the Late Bronze Age. This find highlights the coexistence of multiple languages and cultural traditions within the same territory. It also highlights the Hittites' interest in foreign languages and rituals. The Hittites, known for their multicultural empire, often incorporated elements of conquered cultures into their own society.

This strategy of cultural assimilation demonstrates an understanding and respect for the diversities within their multicultural empire. The Hittites had a tolerant and inclusive approach. By adopting and adapting the traditions of conquered peoples, the Hittites fostered a sense of unity and cohesion within their empire. This integration of various traditions probably played a key role in their stability and longevity.

Furthermore, this discovery suggests a form of syncretism, where different beliefs and practices were merged. Hittite society therefore seemed open to outside influence and flexible in its beliefs. This is a characteristic that may have contributed to the empire's diplomacy and international relations.

Finally, on a historical level, the language of Kalašma sheds light on the linguistic and cultural dynamics of Anatolia at that time. It challenges previous perspectives on the cultural and linguistic monolith of the region. This opens new avenues of research for historians and linguists. They can now explore in more depth the interactions between the different cultures and languages of ancient Anatolia.

Source: websites