Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan (Qubilai-Qan) was the ruler of the Mongol Empire from 1260 to 1294. His accomplishments include establishing Mongol rule in China under the name of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), thus becoming the first non-Chinese to rule the whole of that country. He founded his capital at Xanadu (Shangdu) and established Daidu (Beijing) as its successor.

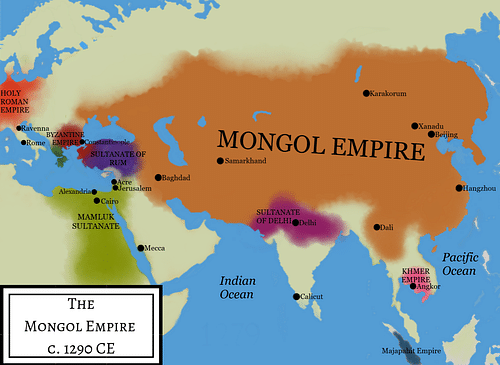

During the reign of Kublai Khan the Mongol Empire expanded to its greatest ever size so that it stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Korean peninsula. There were setbacks along the way, including a series of campaigns with mixed results in South East Asia and two failed invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281. Kublai, the last of the great Mongol rulers, died of illness exacerbated by his repeated overindulgence in food and alcohol; his tomb has never been found.

Kublai Khan Statue

Early Life

Kublai was born in 1215, the second son of Tolui (c. 1190 - c. 1232) and so the grandson of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227), founder of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368). While Kublai's elder brother Mongke (r. 1251-1259) was the ruler of the Mongol Empire, Kublai was given the position of viceroy (ilkhan) of Mongol-controlled northern China. Kublai bided his time and took the opportunity to create a network of support and a team of talented advisors, notably Liu Bingzhong (1216-1274). From 1253, Kublai also personally campaigned alongside Mongke in his attacks on southern China, still controlled by the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Mongol forces moved through Tibet and into Yunnan, subduing the Dali Kingdom in 1257. From here the Mongols could strike at the weak underside of Song China and so a four-pronged attack was planned to invade from the south and west. However, barely under weigh, the campaign came to a halt following Mongke's unexpected death from illness on 11 August 1259.

KUBLAI KHAN CONQUERED THE SONG DYNASTY & UNIFIED CHINA FOR THE FIRST TIME IN FOUR CENTURIES.

Civil War & Succession

When Mongke died in 1259, the campaigns against the Song were abandoned as there quickly developed a scramble amongst the Mongol commanders over who might be his successor. A civil war ultimately broke out between the two main candidates: Kublai and his younger brother Ariq Boke (1219-1266), both of whom declared themselves the new khan. The situation of two khans would not be resolved until 1264, even if in 1260 a meeting of the Mongol tribal chiefs, a kurultai, officially proclaimed Kublai the Great Khan ('universal ruler') of the Mongol Empire.

Ariq Boke was popular because of his conservatism (while Kublai was seen as a bit too Chinese-thinking nowadays), and he had the advantage of controlling the central part of the empire and its capital Karakorum. Kublai would, though, win in the end thanks to support from princes in Central Asia, his control of the Mongol imperial bodyguard and the vastly superior resources at his disposal as viceroy of China. Being the Great Khan remained a prestigious title but, in reality, the empire had already broken up into various khanates, each ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan. Kublai might now rule the biggest and richest portion of what had been the Mongol Empire but what he really wanted was a far older and even more prestigious position: the Chinese Emperor, the ambition of many a steppe nomad for centuries.

Portrait of Kublai Khan

Song Dynasty China

In 1268 Kublai seriously set his sights on the lands south of the Yangtze River and the great prize of Song China. The campaign would be long and arduous, with the Song able to field an army of over 1,000,000 men and both sides equipped with the very latest gunpowder weapons, catapults, and siege machinery. There would also be naval battles involving the largest ships yet seen in the history of warfare. The success of Mongol Warfare across Asia had been based on fast cavalry but the Song countered this by deliberately adopting a strategy of more static warfare and building great fortifications at key cities and river crossings. For this reason, it was going to take eleven long years for Kublai to pick off his targets one by one and finally batter the Song into submission.

The attack on the strategically important fortified city of Xiangyang was typical of the campaign. Besieged for five years, it fell in 1273 thanks to persistence and superior catapults (made from designs come across in Afghanistan). Then, in early 1275, the Khan called another kurultai, this time to decide how to proceed in the last stage of his campaign against the Song. The Mongols crossed the Yangtze in March 1275 and proved unstoppable, winning a massive land and sea battle. With many Song generals defecting or surrendering their armies, a court beset by infighting between the child emperor's advisors, and the ruthless slaughter of the entire city of Changzhou, the end of the Song Dynasty was nigh. The empress dowager and her young son Emperor Gongzong (r. 1274-5) surrendered along with their capital Lin'an on 28 March 1276. The Song royals were taken prisoner to Beijing.

Groups of loyalists fought on for three more years, installing two more young emperors in the process (Duanzong and Dibing), but the Mongols swept all before them. The Song had been rich enough but paid dearly for their lack of political unity, the absence of military investment that had been a feature of past Chinese warfare, an absence of mobile cavalry, and generally poor weapons innovation. Finally, on 19 March 1279 a great naval battle was won at Yaishan near modern-day Macao; the Mongol conquest of China was complete. It was the first time that country had been unified since the 9th century.

Mongol Empire Under Kublai Khan

Arienne King (CC BY-NC-SA)

Xanadu & Daidu

In 1263 the Mongol capital was moved from Karakorum in Mongolia to the more advantageously placed Xanadu (Shangdu) in northeast China. Karakorum had unpleasant associations for Kublai because Ariq Boke had used it as his base before Kublai captured it in 1262. Xanadu, designed by Liu Bingzhong, was given earth circuit walls and towers, creating the classic Chinese square plan for the whole city. Within was a magnificent palace complex complete with hunting gardens. The entire city covered 25,000 hectares and boasted a population of around 200,000 people at its peak.

In 1273 Xanadu was relegated to being only the summer capital of the Mongol Empire, and Daidu (aka Khanbaliq and now Beijing) was selected as the main capital. Daidu, construction of which had begun back in 1266-7, became a potent symbol of the Mongol takeover of China. Kublai divided his time between these two cities and continued to enjoy traditional Mongol pastimes like hunting and drinking fermented mare's milk.

Yuan Dynasty China

Making himself emperor of China, Kublai gave himself the reign name Shizu and, in 1271, his new dynasty the name 'Yuan', meaning either 'origin' or 'centre, main pivot.' The khan, now emperor, embraced Chinese culture, unlike his Mongol predecessors - wearing the traditional robes of an emperor and riding in a sedan chair instead of a horse, for example. This was all part of his campaign to appear to the Chinese as their rightful ruler. The emperor surrounded himself with Chinese ministers and Confucian advisors, even if, behind the scenes, all the key positions of state were given to non-Chinese, especially members of the Mongol imperial bodyguard and, in the area of finance, Muslims who were considered the experts in that field.

Key administrative positions in the newly created 12 semi-autonomous provinces that China and northern Korea (annexed in 1270) was now divided into also went to Mongols. The traditional six Chinese ministries, in place since the Tang Dynasty (618-907), continued as before, but Kublai abolished the civil service examinations which would have favoured Chinese officials with their Confucian education. Finally, there was no Chinese imperial court protocol at the Mongol capital of Karakorum. Clearly, the look-like-a-Chinese-emperor routine was for the benefit of the Chinese only.

Kublai ensured that Mongols always gained an advantage in China by officially classing them as superior in rank to Chinese. There were other measures of segregation, too, such as forbidding Chinese to take Mongol names, wear Mongol clothes or learn the Mongol language. Intermarriage was discouraged and different punishments were meted out for the same crime depending on the race of the guilty. Rather than being a solely racially-motivated policy, though, Kublai was most concerned with controlling his subjects, making it easier to identify who was who and ensuring there were no rebellions; Chinese were forbidden to carry weapons and congregate in public, for example.

The emperor did make some serious attempts to bring the many peoples of his empire together by encouraging the use of different languages in his administration, tolerating different religions, and even ensuring different food dishes were served at the imperial court. Kublai himself converted to Tibetan Buddhism, a move likely influenced by his most important wife and advisor, Chabi (aka Cabui-qatun, d. 1281) and the Tibetan monk Phags-pa Lama (1235-1280). The latter was charged with creating a new official language (based on Tibetan and Sanskrit) which Kublai hoped might be a further bond between the many nationalities under his rule but the idea never caught on outside the court.

Another definite policy was to promote international trade. Artisans were one group who benefited from the Mongol takeover as previously they had been given a low social status. The Mongols, being nomads, perhaps, were unusually impressed with fine porcelain and artworks and so Kublai gave artisans tax exemptions. Merchants, not being producers but 'exchangers,' had been similarly discriminated against, and these, too, now benefitted from more favourable tax measures and the end of sumptuary regulations. Merchants were encouraged to use paper money, currency exchanges were better regulated, and more roads and canals aided the transport of goods. The effect of these policies was to create a boom in trade, especially of fine porcelain. Kublai did the same for other professions whose practical contributions to society impressed him such as doctors and astronomers.

Marco Polo Statue

Marco Polo

The Venetian traveller Marco Polo (1254-1324) set off in 1271 and famously crossed Asia to reach China during the reign of Kublai Khan. Between c. 1275 and 1292 Marco even served the khan, seemingly in the capacity of a roving ambassador/reporter on the more remote parts of the Mongol Empire. On his return to Europe, Marco wrote of his experiences in his book The Travels of Marco Polo, first circulated c. 1298. His descriptions are amongst our best sources for the Yuan Dynasty and the emperor, in particular. He had the following to say about Kublai's physical appearance:

Kublai, who is styled grand khan, or lord, is of the middle stature, that is, neither tall nor short; his limbs are well-formed, and in his whole figure there is a just proportion. His complexion is fair, and occasionally suffused with red, like the bright tint of the rose, which adds much grace to his countenance. His eyes are black and handsome, his nose is well-shaped and prominent. (112)

The Invasions of Japan

Rewinding to 1268, just why Kublai wanted to include Japan in his empire while he was still fighting the Song is unclear. He may have been interested in its resources (especially gold), prestige may have been a factor as conquest had been a traditional method for Mongol leaders to cement their position of power, or he may have wanted to stop the trade between Japan and Song China, thus weakening his number one adversary. Conquering Japan would have given him access to an army which included well-trained samurai or the invasion may even have been some sort of revenge for the havoc that the wako (Japanese pirates) had been causing to East Asian coastlines and trade ships.

Whatever Kublai's reasons, the approach was clear: diplomacy first, warfare second. From 1268, Kublai sent ambassadors but their demands for tribute were totally ignored, except that Japanese troops were put on alert in areas where any invasion seemed likely. This was just as well since Kublai lost patience and amassed a fleet of some 800-900 ships and dispatched it from Korea in November 1274. The ships carried an army of some 16,600-40,000 Mongols, Chinese, and Koreans. The Mongol attacks met stiff resistance on the outer islands but the invasion fleet proceeded to Hakata Bay, landing on 19 November.

The Mongol Scroll, 1293 CE

Prepared they may have been, but the total Japanese defence force was still a paltry 4,000-6,000 men. The Mongols won the first engagements thanks to their superior numbers, weapons, and mass coordinated troop movements which the Japanese were not used to as they favoured allowing individual warriors to pick their own single target in their version of medieval warfare. Curiously, though, the invaders did not push deeper into Japanese territory. Perhaps this was because of supply problems or the death of the Mongol general Liu Fuxiang. It may also be true that the whole 'invasion' was actually only a reconnaissance mission. Whatever the motive, the invaders remained by their ships for the night, withdrawing out into the bay for safety on 20 November. This was a fateful decision because, in some accounts, a terrible storm then struck which killed up to a third of the Mongol army and severely damaged the fleet. The attackers were thus obliged to withdraw back to Korea.

Kublai Khan returned to diplomacy and sent two more embassies to Japan in 1275, demanding, once again, tribute be paid. This time the Japanese were even more dismissive and beheaded the ambassadors. The Japanese used this interlude to built more fortifications and ready themselves for the inevitable second invasion.

Kublai Khan's invasion fleet of June 1281 was a whole lot bigger than the first one. This time, thanks to his recent defeat of the Song and acquisition of their navy, there were 4,400 ships and around 100,000 men, again a mix of Mongol, Chinese, and Korean warriors. Again, Hakata saw the brunt of the fighting, but the new fortifications there withstood the test. After heavy losses, the Mongols withdraw to Iki Island only to be harassed by Japanese ships making constant raids using small boats. Kublai was, though, able to dispatch reinforcements from China, perhaps another 40,000 men. The combined fleets then moved east and attacked Takashima, a battle there taking place on 12 August.

Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1281 CE

Fierce fighting raged for several weeks and the invaders likely faced shortages of supplies. Then, yet again, the weather intervened and caused havoc. On 14 August a typhoon destroyed most of the Mongol fleet, wrecking ships that had been tied together with chains for safety against Japanese raids and smashing the uncontrollable (and not particularly well-built) vessels against the coastline. From half to two-thirds of the Mongol force was killed and thousands more were washed up or left stranded on the beaches of Imari Bay, where most were executed. Those ships that survived sailed back to China. The storm winds that either sunk or blew the Mongol ships safely away from Japanese shores were given the name kamikaze or 'divine winds' as they were seen as a response to the Japanese appeal to Hachiman, the Shinto god of war, to send help to protect the country against a vastly numerically superior enemy.

Death & Legacy

Like Japan, southeast Asia was attacked in various land and naval campaigns but they also proved an elusive prize with invasions of Vietnam (1257, 1281, and 1286), Burma (1277 and 1287) and Java (1292) achieving only limited success where Mongol armies faced such unfamiliar experiences as humid jungles, parasitic diseases, and war elephants. Kublai never gave up on Japan and continued to send unsuccessful diplomatic missions to persuade the country to join the Chinese tribute system.

Kublai's later reign was, then, a little disappointing, but he had managed to foster a relatively peaceful situation across Asia, the so-called Pax Mongolica. There were the odd rumblings of discontent, especially when taxes were raised to fund Kublai's immensely expensive foreign exploits. There was a major rebellion in Tibet in the early 1290s, and the other descendants of Genghis Khan, especially the Ogedeids, continued to nibble at China's western borders. The emperor's health was deteriorating, too, and, grossly overweight, Kublai suffered from chronic gout and rheumatism.

Kublai died of natural causes in 1294 at the age of 79 or 80 - an extremely old age for often hard-living Mongol rulers. The body was taken to a secret location, probably in Mongolia, as was the tradition, and buried, most likely in an extravagant tomb, but this has never been found. Kublai was succeeded by his grandson Temur as Khan and emperor of China (r. 1295-1308) after his first choice, his son Zhenjin (1243-1285), died prematurely. The Yuan Dynasty that Kublai had founded enjoyed some 30 years of stability but was thereafter beset by dynastic disputes and never again reached the heights of Kublai's reign. The Yuan would rule China until the arrival of the Ming Dynasty in 1368.

Thanks to Marco Polo and others, the power and wealth of Kublai's court and empire have held a lasting grip on the world's imagination and made his summer capital of Xanadu a byword for opulence and pleasant living. Genghis Khan may have grabbed posterity's accolades for the greatest and most fearsome Mongol military leader, but Kublai has gained the lasting reputation as the man who reaped the rewards of Mongol supremacy in the Middle Ages and became, in western eyes, forever the quintessential oriental potentate.

Kublai Khan: China’s Mongol Emperor

Bibliography

Buell, P.D. Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2018.

Dillon, M. China: A Cultural & Historical Dictionary. Routledge, 1998.

Ebrey, P.B. Pre-Modern East Asia. Cengage Learning, 2013.

May, T. The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Morgan, D. The Mongols. Wiley-Blackwell, 2019.

Polo, M. The Travels of Marco Polo. Penguin Classics, 1958.

Rossabi, M. A History of China. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Turnbull, S. Genghis Khan & The Mongol Conquests 1190-1400. Osprey Publishing, 2003.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language! So far, we have translated it to: Portuguese, Dutch, Bosnian, Italian, Greek, French, Afrikaans

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE

https://www.worldhistory.org/Kublai_Khan/