Wolof Empire

Wolof Warrior

The Wolof (aka Jolof or Djolof) Empire was a state on the coast of West Africa, located between the Senegal and Gambia rivers, which thrived from the mid-14th to mid-16th century CE. The empire prospered on trade thanks to the two rivers providing access to the resources of the African interior and coastal traffic, commerce which included gold, hides, ivory, and slaves, and which was often carried out with European merchants, notably the Portuguese and then the French. Following the break-up of the Wolof Empire in the 16th century CE, a smaller state persisted, the Wolof Kingdom, into the 19th century CE. The Wolof language is still widely spoken today in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania.

Early History

The Wolof as a people inhabited, from the 1st millennium BCE, the area between the Senegal River in the north and the Gambia River in the south. This West African region is often called Senegambia and covers what is today Senegal, Gambia, and southern Mauritania. Language and pottery both suggest that the ancestors of the Wolof had originally migrated here from central or eastern Africa. They fished, grew wet rice, and herded cattle, sheep, and goats (and later, pigs). They used iron for tools, pottery, and jewellery. The people of this area of West Africa also set up megalithic monuments and burial markers. Circles were formed some 8 metres (26 ft.) in diameter using stones up to 4 metres in height.

THE WOLOF EMPIRE WAS A MAJOR PARTICIPANT IN THE SLAVE TRADE, EXPORTING AS MUCH AS ONE-THIRD OF ALL AFRICAN SLAVES PRIOR TO 1600 CE.

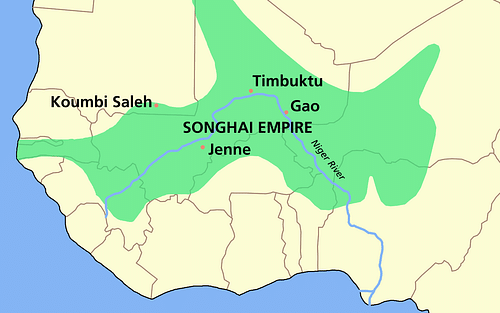

The Wolof eventually became the most powerful tribe south of the Senegal River. This territory had once been under the nominal control of the Mali Empire (1240-1465 CE) after a successful campaign of expansion by Tiramaghan, a general of Sundiata Keita (r. 1230-1255 CE), the Mali king. The relationship between the two states is unclear, but the Wolof seem to have at least acknowledged the Mali kings as the main West African power. Wolof's independence can be seen in the succession of their first king or burba, the semi-legendary Ndiadiane N'diaye, traditionally placed in the 13th century CE but more likely to have been in the second half of the 14th century CE. In any case, civil wars, attacks from tribes such as the Mossi people and the shift of lucrative trade routes, meant that the Mali kings slowly lost their grip on the outer regions of their empire. Around 1468 CE, King Sunni Ali (r. 1464-1492 CE) of the Songhai Empire (c. 1460 - c. 1591 CE) then conquered the rump of the ailing Mali Empire.

Map of Ancient & Medieval Sub-Saharan African States

The Songhai were only present south of the Gambia River, and this permitted the Wolof in the north to exploit one of the few vacant areas the Songhai Empire did not control in West Africa (either through direct occupation or the enforcement of tribute). By the end of the 15th century CE, the Wolof Empire consisted of the three Wolof-speaking kingdoms of Cayor (Kajoor), Walo (Waalo) and Baol (Bawol), and states populated by speakers of Serer such as Sine and Salum. Eventually, the Wolof kings expanded into the Malinke territory north of the Gambia River which included the states of Nyumi, Badibu, Nyani, and Wuli. Consequently, the Wolof kings came to rule the whole of Senegambia, although this state may better be described as a confederacy of tribute-paying kingdoms rather than an empire proper (as it is often called).

Trade: West Africa & Portugal

The Wolof Empire was a major participant in the slave trade, exporting as much as one-third of all African slaves prior to 1600 CE. This trade declined in the 17th century CE as Senegambia became a thoroughfare of slaves from the interior of central Africa rather than a source of them. Thanks to the mighty Senegal River, which extends hundreds of kilometres into Africa's interior, the Wolof were in a position to trade all manner of goods besides slaves, and these included hides, cotton textiles, gum, ivory, kola nuts, salt, horses, indigo, and beeswax. The Wolof also had their own manufacturers to transform raw materials into even more valuable goods. Wolof goldsmiths and filigree workers enjoyed an especially high reputation across West Africa.

The major commodity traded through Wolof territory was, though, none of the above; it was gold. The precious metal, so beloved by the Europeans who were beginning to take a serious interest in Africa south of the Sahara, come from the inland Bambuk goldfields and eventually found its way to the coast. The Portuguese began trading up and down the coast of West Africa in the mid-15th century CE. The adventurer Diogo Gomes established trade relations with the Wolof in 1455 CE, and trade blossomed between the two powers. Gifts were exchanged between the king of Portugal, John II (r. 1481-1495 CE) and the Wolof, and Christian missionaries were received.

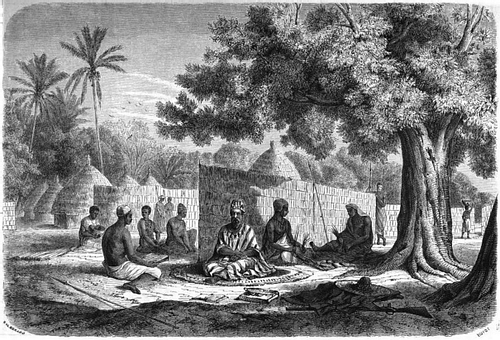

Wolof Chief & Residence

The trade with the Portuguese become so lucrative through the 1480s CE that the Wolof king, Burba Birao, even shifted his capital nearer to the coast. However, not everyone was happy with the welcoming of missionaries, and traditionalist princes led a revolt which toppled Burba Birao in 1489 CE. Birao's brother, Prince Bemoi, was forced to flee the country, but he was given a splendid welcome in Lisbon where he was even baptised. By 1490 CE, the Portuguese were ambitious to control directly trade goods, and particularly gold, from their source in Africa's interior. They sent a military expedition against the Wolof king and backed Prince Bemoi to take the throne. The expedition, despite involving 20 caravel ships, proved a failure because of disease and a serious disagreement between the pretender and his European backers, which led to the former's death. Thereafter, the Portuguese remained within their fortified trading posts along the coast as trade continued through the 16th century CE.

THE RELIGION OF THE ELITE, AT LEAST NOMINALLY, WAS ISLAM DUE TO ITS SPREAD BY BERBER TRADERS, CLERICS & MISSIONARIES.

The Wolof State

Portuguese contact at least gives us some information on the Wolof state. We know that the king was elected by a council of elders from candidates who belonged to a certain ancestry, most likely the actual founder of the Wolof state. Some members of this council were rulers of the individual states within the Wolof confederacy. Wolof society was hierarchical with several distinct classes. The royal family was at the top, then non-royal nobles (often the children of secondary wives and concubines of royalty), and free men. The latter category was further divided into castes depending on a man's occupation such as blacksmiths, jewellers, tailors, griots (epic storytellers), and musicians. At the bottom of society were slaves taken during wars and raids in neighbouring territories, and who were themselves divided into strata with skilled slaves at the top and unskilled agricultural labourers at the bottom. There was also a class of military slaves, the ceddo, which the elite used to enforce the payment of tribute and police other slaves. The religion of the elite, at least nominally, was Islam due to its spread by Berber traders, clerics and missionaries. In contrast, most of the ordinary population remained close to their traditional animist beliefs.

Trade: West Africa & France

In the last quarter of the 16th century CE another major power arrived in the region: France. The French traders brought with them such highly desirable items as textiles from northern France, spirits, metal goods, pepper, palm oil, and firearms. The Portuguese soon lost their trade advantage, especially as the export of the much-in-demand firearms to Africa was prohibited by the Portuguese crown. Consequently, the French gained control of such towns as Gorée, Portudal, Joal, and Rufisiique, all in Wolof territory. The European's presence was such that populations in the urban areas along the Atlantic coast eventually became mixed African and French, as seen at, for example, the port of Saint Louis. By the end of the 16th century CE, the English and the Dutch were also a significant trading presence in the region as the gold and slaves of Africa proved just as irresistible to them as the French and Portuguese.

Break-up

Trade might have been booming but the Wolof Empire itself began to disintegrate as early as the mid-16th century CE, breaking up into a number of successor states which included what is today referred to as the Wolof kingdom. This initial break-up was likely caused by the coastal towns growing so rich on trade that they sought to break away from the central Wolof monarchy. Indeed, these provinces were the first to claim their independence. The Wolof were also weakened by the rise of the militaristic Fulani, first led by Koli Tengella (c. 1512-1537 CE), who set up his state in Futa Toro, a territory around the middle section of the Senegal River. The group of now disparate states in Senegambia, split between speakers of Wolof and Serer, was composed of Waalo, Cayor, Bawol, Siin, Saalum and the Wolof kingdom (unfortunately for it, the only one without access to the coast).

The Successor Kingdoms & Islam

Despite the political upheaval, though, the Senegal River remained what it always had been: a vital thoroughfare into and out of Africa's interior. The small kingdoms saw their rulers establish lucrative monopolies on the trade of such high-value goods as slaves and firearms. Indeed, the region was siphoning off so much trade previously controlled by the North African states and their middlemen the Saharan Berbers that the latter's marabout or religious leader, Nasir al-Din (r. 1644-1674 CE) launched a holy war in 1673 CE. As the UNESCO General History of Africa Vol. V summarises:

The proclamation of war…was motivated by both economic and religious considerations, to reconquer the trade in grain and slaves and to convert the peoples and purify the practice of Islam…From being the religion of a minority caste of merchants and courtiers in the royal courts, it was becoming a popular resistance movement against the arbitrary power of the ruling autocracies and against the noxious effects of the Atlantic trade. (141)

Consequently, with the support of the people and those already converted to Islam, the war resulted in the sweeping away of the ruling elite in many of the successor kingdoms of the Wolof Empire. The new regimes became Muslim theocracies but they did not last long. With the death of Nasir al-Din in 1674 CE, numerous defeats, and the French intervening in support of the kingdoms, the Berbers were pushed back and the holy war fizzled out. The successor kingdoms, far from taking this as a timely reminder of their weakness as small competing states, continued to bicker and fight amongst themselves. Popular movements rallied around the idea to spread Islam, and the kingdoms, beset by other problems such as a series of famines, disintegrated as political entities by the beginning of the 18th century CE.

The Wolof people were still actively involved in the coastal trading in the mid-18th century CE but the region became increasingly dominated by the French from the early 19th century CE as they and other European powers now took direct control through military conquest of the parts of Africa that interested them. The Wolof language, however, far outlasted the empire or kingdom and is today the official language in Senegal (along with French) and is widely spoken in several other West African states.

Bibliography

Curtin, P. African History. Pearson, 1995.

Hrbek, I. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. III, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1992.

Ki-Zerbo, J. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1998.

McEvedy, C. The Penguin Atlas of African History. Penguin Books, 1996.

Mokhtar, G. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. II, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1990.

Ogot, B.A. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. V, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1999.

Oliver, R. (ed). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Oliver, R.A. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa. Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Searing, J.F. "Aristocrats, Slaves, and Peasants: Power and Dependency in the Wolof States, 1700-1850." The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 21, No. 3 (1988), pp. 475-503.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Wolof_Empire/