Sundiata Keita

Cavalry Warrior, Mali Empire

Sundiata Keita (aka Sunjaata or Sundjata, r. 1230-1255 CE) was the founder of the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE) in West Africa. A prince of the Malinke tribe, Sundiata would not only overthrow the rule of the kingdom of Sosso (c. 1180-1235 CE), the biggest inheritor of the crumbling Ghana Empire (6th -13th century CE), but go on to conquer neighbouring kingdoms, establish stable government from his capital Niani, and make his empire the largest and richest yet seen in West Africa. Sundiata Keita, whose name means 'lion prince', was so fundamental to the creation of the Mali Empire and the history of the Malinke that ancient indigenous oral traditions have built him up into a great warrior and hunter-magician figure whose exploits ensured his descendants would reign over the region for centuries.

Early Life & Legends

The life and deeds of Sundiata Keita are largely derived from oral traditions repeated by the griots, the oral storytellers whose tales, recounted over generations, were eventually put down in writing and then translated by European historians in the 19th century CE. As the historian P. Curtin puts it, "[Sundiata's] position in the oral literature of the western Sudan is equivalent to that of Charlemagne in western Europe" (94). Added to these stories, but often not entirely matching them, are works by medieval Arab chroniclers.

SUNDIATA'S NAME MEANS 'LION PRINCE' OR 'HUNGERING LION', THE BIG CAT BEING THE SYMBOL OF THE KEITA CLAN.

According to the legend, Sundiata was a prince of the indigenous Malinke (aka Mandingo) ethnic group, and his name, appropriately enough, means 'lion prince' or 'hungering lion', the big cat being the symbol of the Keita clan. Born into a royal family in 1210 CE, Sundiata had an immediate disadvantage in that he could not walk, a deformity perhaps linked to his mother who was a hunchback in some versions of the Sundiata stories. It was for this reason that an enemy of his father had spared his life, the suspicious monarch having already killed 11 other male offspring of Sundiata's father to ward against a future rebellion of his rule. When he was around seven years old Sundiata began to wear iron leg braces and with these and much painful practice, the young prince was eventually able to walk unaided. In one version of the stories, Sundiata had other problems as he was exiled to the kingdom of Mema while a brother, Dankaran Tuman, took over as ruler of the Malinke. However, Sundiata was later persuaded to return home to help liberate his people from oppressive foreign rule.

Collapse of the Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire (not geographically connected to modern Ghana) began to collapse at the end of the 12th century CE after having dominated central West African trade in the upper valley of the Niger River since the 6th or 7th century CE. Really a conglomerate of villages ruled by a single king, the empire prospered thanks to a well-trained army and access to raw materials such as iron ore to make its weapons and gold deposits to pay its soldiers. Control of regional trade was a lucrative business for the kings of Ghana who passed on goods like gold and ivory to the Muslim merchants who sent camel caravans that crossed the Sahara from North Africa and which brought much-valued salt to the south.

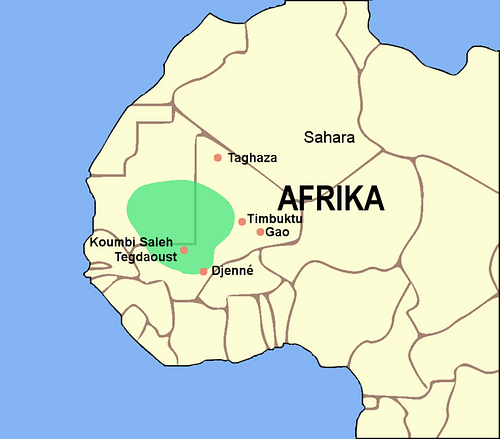

The Ghana Empire

The decline set in when other competing trade routes opened up and when the climate became unusually dry for a prolonged period which affected agricultural production. The rulers of Ghana did not help themselves either as the empire was beset by a string of civil wars. As ever, empires fall and others rise, and Sundiata Keita was intent that it would be his star that rose above all others in West Africa. Malinke lands had always proved troublesome for the Ghana kings to control and rebellions were rife from the early years of the 13th century CE onwards, especially when the last rulers of the fast-crumbling Ghana Empire, the Sosso (aka Susu), imposed restrictions on trade in parts of their territory.

From the 1230s CE Sundiata waged all-out war against the Sosso and their king Sumanguru (aka Sumaoro Kante, r. from c. 1200 CE). Sundiata had formed a powerful alliance of other disgruntled chiefs tired of Sumanguru's harsh rule, and more importantly, he was given invaluable help from his sister, Nana Triban. Nana had been forced to marry Sumanguru, and she had discovered the secret that his totem (tana) or source of strength was a white cockspur. Nana stole the cockspur and so Sumanguru was at a severe disadvantage in the coming battle at Krina (aka Kirina) in 1235 CE. Sundiata and his allies were victorious, and Sumanguru fled for his life, never to be seen again.

Sundiata, aided by gifted generals - in particular, Tiramaghan Traore and Fakoli Koroma - would win more victories, and he eventually seized the old Ghana capital in 1240 CE. Not only did Sundiata win independence for his people but he also went on to establish his own impressive kingdom what would become known as the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE), Mali being the local term for 'the place where the king lives'.

Government & The Mali Empire

Sundiata is credited in oral tradition with establishing a code of government which covered rules for both political and social behaviour in the Mali Empire. First, a great assembly was gathered of tribal chiefs to officially proclaim Sundiata the supreme monarch. Indeed, Sundiata would acquire a suitably large number of titles for such a powerful ruler, including Maghan or Mansa (King), Nfa Mansa (My Father, the King), Simbon Salaba (Master Hunter) and Mari Diata (Lord lion).

Terracotta Head from Mali's Inland Niger Delta Region

The clan leaders also decreed that all future Mali kings would be selected from Sundiata's descendants. Clans were reorganised, sometimes according to professions, and given new or alternative names to establish greater unity across the kingdom. The assembly also decreed that trades such as blacksmiths, weavers, and shoemakers were to be made hereditary. In short, Sundiata carefully allotted each tribal group and each person within them a defined role as part of a larger empire where loyalty and solidarity were fostered.

SUNDIATA'S CENTRAL GOVERNMENT AT NIANI WAS COMPOSED OF LOYAL TRIBAL LEADERS WITH AN ADDITION OF A SELECT NUMBER OF ARAB TRADERS.

Niani, now no longer in existence and probably located on a plain near the all-year-round navigable Sankarani River, was selected as the Mali Empire's new capital. Protected by mountains and close to the two key sources of trade goods: forests and waterways, the city quickly became a cosmopolitan centre, declared by Sundiata an imperial territory where all the peoples of the empire were welcome. Sundiata's central government at Niani was composed of loyal tribal leaders with an addition of a select number of Arab traders, useful for their foreign commercial and political contacts. The empire as a whole was divided into north and south, with each part given a military governor. To ensure compliance in all the territories of the empire, many local chiefs were permitted to carry on as they had previously but they were given an appointed governor (farin) and sometimes a government-paid garrison was established. Thus, the empire really functioned as a federation of small kingdoms.

The Mali Empire would become the largest and richest empire yet seen in West Africa controlling, like the Ghana Empire had, regional trade routes by land and river and local resources such as gold, copper, iron, and ivory. While most of the population were farmers, the rich elite was composed of merchants who acted as middlemen between the traders to the south and the Berber-controlled caravans that crossed the Sahara to North Africa and the Muslim world. Sundiata would continue to bring new territories under his control, and by the end of his reign, the Mali Empire would control the old kingdoms of Ghana, Walata, Tadmekka, and Songhai. Significantly, these territories included the rich gold-bearing regions of Galam, Bambuk, and Bure.

Map of the Mali Empire, c. 1337 CE

Sundiata & Islam

Noted Muslim travellers and chroniclers like Ibn Battuta (1304 - c. 1369 CE) and Ibn Khaldin (1332-1406 CE) record that Sundiata (sometimes referred to by them as Mari-Jata) converted to Islam like most of his successors - that religion being spread by Arab merchants in the region. However, the Malinke oral tradition, although recognising Islam was present in Mali long before Sundiata's reign, maintains that the first ruler of the Mali Empire did not reject the indigenous animist religion and that he was a powerful magician who most certainly did not convert to any foreign faith. Sundiata must have been aware, though, of the advantages of gaining favour with his powerful trading partners and we do know that Sundiata's son, Mansa Uli (aka Mansa Wali or Yerelenku), went on a pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1260s or 1270s CE. It would not be, though, until the 14th century CE and the reign of Mansa Musa I (1312-1337 CE) that Islam was spread with any great success amongst the urban populations of the Mali Empire. Rural communities, in particular, would continue, in any case, to adhere to their traditional religious beliefs.

Death & Successors

Sundiata Keita died in 1255 CE but quite how is uncertain. Some records point to an accidental but fatal arrow wound, others to drowning in the Sankarani River. His tomb is not known because of the Malinke tradition of never revealing where a king is buried. More certain is Sundiata's legacy, for the king had established a relatively stable empire which a long line of his descendants would rule, starting with his son Mansa Uli (r. c. 1255-1270 CE). The Mali Empire would keep on growing, especially during the reign of Sundiata's grand nephew, Mansa Musa I, who oversaw the largest territorial expansion in West Africa, spread the religion and architecture of Islam, and famously spent tons of gold on a visit to Cairo in 1324 CE.

Soundiata Keita

Bibliography

Curtin, P. African History. Pearson, 1995.

de Villiers, M. Timbuktu. Walker Books, 2007.

Hrbek, I. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. III, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1992.

Ki-Zerbo, J. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1998.

McEvedy, C. The Penguin Atlas of African History. Penguin Books, 1996.

Oliver, R. (ed). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Oliver, R.A. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa. Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language! So far, we have translated it to: Malay, French

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Sundiata_Keita/