Ten Ancient Mesopotamia Facts You Need to Know

Mesopotamia is the ancient Greek name (meaning “the land between two rivers”, the Tigris and Euphrates) for the region corresponding to modern-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Syria, and Turkey. It is considered the “cradle of civilization” for the many inventions and innovations which first appeared there c. 10,000 BCE through the 7th century CE.

In the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Age, people gradually shifted from a hunter-gatherer paradigm to agrarianism, creating seasonal communities which became permanent during the Pottery Neolithic Age (c. 7000 BCE) and served as a basis for the development of cities during the Copper Age (5900-3200 BCE). This last era includes the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) which saw the rise of the first temples (stepped towers known as ziggurats with a shrine at the top) and the creation of intricate art, ceramic work, and copper toolmaking.

Great Ziggurat of Ur

Overlapping this period and the later Early Bronze Age (3000-2119 BCE) was the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) during which cities, trade, government, and the concept of private land ownership developed. The region was never a single, cohesive political entity, even when it was under the control of the first empires to appear in the world, and the diversity of the populace encouraged imagination in innovation in every area of daily life including agriculture, mercantilism, political theory, warfare, as well as the creation of bread, beer, and “good luck” charms.

Many of the most common aspects of daily life, as well as theological paradigms and political systems, developed first in Mesopotamia. The population was only homogenized, relatively speaking, after the 7th century CE, following the Muslim Arab conquests which mandated and regulated religious belief and custom. Below are ten facts regarding the region which are often overlooked or have been misrepresented.

Home of the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent is the quarter-moon-shaped region of ancient Mesopotamia corresponding to modern-day southern Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and northern Egypt. It is the locale commonly referred to as “the Cradle of Civilization” because of the cultural and technological advancements made there which include but are not limited to:

agricultural techniques

domestication of animals

astrology and the development of the zodiac

the concept of time

science and technology

the wheel

writing and literature

religion

mathematics and astronomy

long-distance trade

medical practices (including dentistry).

The designation “Fertile Crescent” is frequently supposed to have originated in antiquity but, actually, was coined in 1916 CE by the Egyptologist James Henry Breasted in his popular book Ancient Times: A History of the Early World. The book's popularity encouraged widespread use of the phrase until it entered cultural consciousness as the name for the region.

Invented Writing, the Wheel, & the City

THE INVENTION OF THE CITY IS AMONG THE MESOPOTAMIANS' MOST SIGNIFICANT INNOVATIONS IN THAT THE CONCEPT, SO COMMON TODAY, NEVER EXISTED BEFORE.

Writing developed independently in many different areas of the world from China to Mesoamerica, but Mesopotamia is considered the first to do so, having created a writing system prior to c. 3000 BCE, known as cuneiform. The wheel also originated in the region (c. 3500 BCE) contrary to claims that it was invented in Central Asia. The oldest wheel in the world, dated to c. 3200 BCE (known as the Ljubljana Marshes Wheel) was discovered in Slovenia in 2002 CE, giving rise to the claim that the people of Central Asia invented the wheel. The Mesopotamian wheel came first, however, as evidenced by its appearance in Mesopotamian art pre-dating c. 3200 BCE.

The invention of the city is among the Mesopotamians' most significant innovations – for better or worse – in that the concept, so common today, never existed before. Cities developed during the Uruk Period when small, agricultural communities, which were thriving, attracted the people of nearby regions who were, perhaps, not doing as well. Mesopotamian cities provided the people with protection from the elements, natural predators, and raiders while also opening up new opportunities for making a living. In this regard, they were at first a great benefit to the people. Eventually, however, the dense population of the cities, and their expansion, depleted the resources around them. Many Mesopotamian cities which were originally thought by archaeologists to have been destroyed in wars were actually abandoned when the resources were used up.

First Recorded War

Among the most important resources in the region was water and this was, most likely, the cause of the first war in recorded history. In c. 2700 BCE, the Sumerian king Enmebaragesi of the city of Kish led his people in a military campaign against the region of Elam (corresponding to parts of modern-day Iran), defeated them, and carried spoils back to Mesopotamia. This is all that is known of the engagement, but it is likely the initial dispute arose over water rights – access to water – and the event is also significant as an example of the city-states of Sumer banding together in the interest of a common cause. As with the Greek city-states, the Sumerian cities frequently fought with each other but, when necessity dictated, they worked together to protect their common interests.

Cylinder Seal from Kish

Invented Beer

Among the many uses the Mesopotamians found for water – irrigation of crops being the priority – was the brewing of beer. Beer was considered the “drink of the gods” and brewing was presided over by the goddess Ninkasi (who lends her name to the modern-day Ninkasi Brewing Company of Eugene, Oregon, USA) who ensured its purity. Beer was the most popular drink in ancient Mesopotamia as it contained so many significant nutrients that it was considered a food and was used to pay the wages of laborers (as it later would be in Egypt). Scholar Jeremy Black comments:

Beer was a staple in Mesopotamia and its surroundings from prehistoric times, as the fermentation process was an effective method of killing bacteria and waterborne disease. Its manufacture was recorded and controlled by scribes even in the earliest written records, from the late fourth millennium BCE. Beer was consumed by people at all levels of society and offered to gods and to the dead in libation rituals. (297)

The recipe for brewing beer was preserved by the Sumerians in The Hymn to Ninkasi which is thought to have been sung or chanted by the brewers as they worked.

Home of the First Firsts

There are many “firsts” associated with ancient Mesopotamia, especially Sumer, and the scholar Samuel Noah Kramer lists, and then discusses, 39 of these in his influential work History Begins at Sumer. The 39 “firsts” below are only the ones Kramer chose to address but there are many more:

The First Schools

The First Case of 'Apple Polishing'

The First Case of Juvenile Delinquency

The First 'War of Nerves'

The First Bicameral Congress

The First Historian

The First Case of Tax Reduction

The First 'Moses'

The First Legal Precedent

The First Pharmacopoeia

The First 'Farmer's Almanac'

The First Experiment in Shade-Tree Gardening

Man's First Cosmogony and Cosmology

The First Moral Ideals

The First 'Job'

The First Proverbs and Sayings

The First Animal Fables

The First Literary Debates

The First Biblical Parallels

The First 'Noah'

The First Tale of Resurrection

The First 'St. George'

The First Case of Literary Borrowing

Man's First Heroic Age

The First Love Song

The First Library Catalogue

Man's First Golden Age

The First 'Sick' Society

The First Liturgic Laments

The First Messiahs

The First Long-Distance Champion

The First Literary Imagery

The First Sex Symbolism

The First Mater Dolorosa

The First Lullaby

The First Literary Portrait

The First Elegies

Labor's First Victory

The First Aquarium

Among the “firsts” not on the list is the first dog collar and leash, represented in early Mesopotamian art. Early dog collars seem to have been little more than ropes or bands of leather tied around a dog's neck but grew progressively more ornate as the civilization developed. The dog-collar-as-art was fully realized by the Egyptians during the era of the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE), when dog collars were ornamented with the name of the dog and owner, but the concept of the collar itself was first developed in Mesopotamia.

Man & Dog Plaque, Sippar

First Multinational Empire

Another of the “firsts” of Mesopotamia is the first multinational empire in the world, the Akkadian Empire (2334 - c. 2083 BCE) founded by Sargon of Akkad (the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE). The precise location of Akkad is unknown but, from Sargon's inscriptions, his empire stretched from the Persian Gulf up through modern-day Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, most likely the Levant, and down through Asia Minor to include the island of Cyprus. Sargon kept his empire intact by placing trusted individuals – both men and women – in positions of political power throughout the region. These officials were referred to as “Citizens of Akkad” in later Babylonian texts and served as governors, high priests or priestesses, or high-level administrators in over 65 different cities. One of these trusted officials was his daughter Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), High Priestess of Inanna at the city of Ur. Even though Sargon was careful to maintain tight control, without oppressing the people, rebellions still broke out. The empire retained its cohesion up through its greatest king, Sargon's grandson, Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE) but declined under his son and successor Shar-Kali-Sharri (r. 2223-2198 BCE) and finally fell to the Gutians in c. 2083 BCE.

Akkadian Ruler

First Author Known by Name

Enheduanna was not only the High Priestess who helped maintain her father's empire in Sumer but also an accomplished poet and the first author known by name in the history of the world. She is best known for her three great hymns to the goddess Inanna: The Great-Hearted Mistress, The Exaltation of Inanna, and Goddess of the Fearsome Powers but she also wrote 42 poems relating her personal feelings on a number of different subjects. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

The hymns provide us with the names of the major divinities the Mesopotamians worshipped and tell us where their chief temples were located [but] it is the prayers that teach us about humanity, for in prayers we encounter the hopes and fears of everyday mortal life. (172)

Her poems and hymns were extremely popular and influenced later hymns, songs, poems, and psalms, notably those of the biblical Old Testament. The biblical Song of Songs is influenced by Enheduanna's verse and her works are still read and widely appreciated in the present day.

Invented Literature

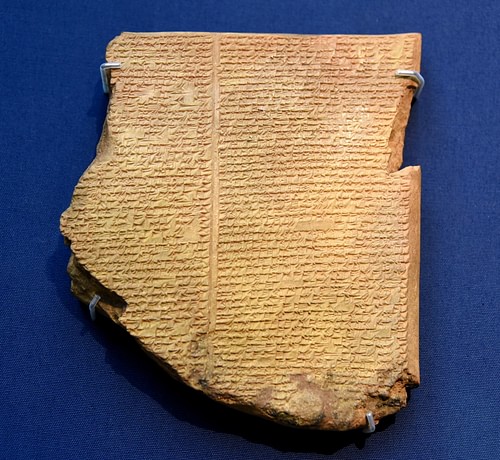

The Mesopotamians not only influenced the later development of sacred liturgical texts but also invented literature beginning with The Epic of Gilgamesh (written c. 2150-1400 BCE) which famously tells the tale of the semi-mythical King of Uruk, Gilgamesh, and his quest for meaning in life in the face of inevitable death. The work was originally passed down orally until it was set down in written form. Prior to the discovery of Enheduanna's work, the world's first author known by name was thought to be the Babylonian scribe Shin-Leqi-Unninni (worked 1300-1000 BCE) who wrote the Babylonian version of the tale. The Epic of Gilgamesh, a fictional tale based on an actual king, is representative of a genre known by modern-day scholars as Mesopotamian Naru Literature which first appeared around the 2nd millennium BCE. These tales featured a famous person (usually a king) in a fictional story whose theme was usually one's relationship to the gods but could be on any subject. The two best-known examples of Mesopotamian Naru Literature, besides Gilgamesh, are The Legend of Sargon – which relates Sargon the Great's humble birth and rise to power – and The Curse of Agade – which deals with Naram-Sin. These stories were quite popular throughout Mesopotamia and influenced later writers, quite possibly the scribes who wrote the biblical narratives of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ which make up the Gospels of the New Testament.

Flood Tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh

Myths Became Biblical Narratives

Whether Mesopotamian Naru Literature directly influenced the composition of the Gospels is disputed – although the form of the compositions is similar in that the Gospels also feature a central character who was well known placed in situations which may or may not have actually happened – but it is a certainty the Mesopotamian myths influenced the biblical tales of the Fall of Man and The Great Flood and also the Book of Job. These stories were all adapted from the Mesopotamian works The Myth of Adapa, The Eridu Genesis, The Atrahasis, and the Ludlul-Bel-Nimeqi, the last of which deals with a good man's lament over his misfortunes and his questions regarding the justice of the gods. Prior to the mid-19th century CE, when European and American institutions funded expeditions to Mesopotamia to find physical evidence to corroborate biblical narratives, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world containing wholly original works; afterwards, these works were understood as inspired by or adapted from Mesopotamian works.

First Law Codes

Although the law code of the Babylonian king Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE) is well known, it was not the first law code in the world nor even the first in Mesopotamia. The earliest law code was the Code of Urukagina in the 24th century BCE and the second was the Code of Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE), founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur in Sumer which initiated the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE). It is possible Ur-Nammu's code was actually written by his son and successor Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE), but, if so, it was most likely either based on his father's code or written in accordance with his father's precepts. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek comments:

Although it is neither a true law code, being far from comprehensive; nor, some say, even introduced by Ur-Nammu but by his son Shulgi, code or no, although we only have fragments, they are enough to show that the laws covered both civil and criminal matters. Among criminal provisions it specifies which should be capital offences: murder, robbery, deflowering another man's virgin wife, and adultery when committed by a woman. For other misdemeanors the penalty was a fine in silver… [Ur-Nammu's code stands] in contrast to the more famous laws of Hammurabi, drafted some three centuries later, with its savage provisions of 'an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth'. (148-149)

The Code of Ur-Nammu would influence the later Code of Hammurabi in making clear the punishments for offenses and legitimizing itself as issued from a divine source. The Code of Hammurabi was necessarily harsher because he ruled over a more diverse population, which did not share the same theological vision concerning the gods and their dispensation of justice.

Law Code of King Ur-Nammu

Conclusion

The above are only some of the Mesopotamian contributions to world culture. They also pioneered cartography, developing maps between 2360-2180 BCE. They influenced Greek philosophy through the Pre-Socratic philosopher Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE) who studied in Babylon and claimed that water was the First Principle of existence based on what he learned there. The concepts of town planning and zoning also developed in Mesopotamia where a commercial district was distinct from residential and city streets were planned out for ease of travel. The Assyrian Empire (c. 1307-612 BCE) was the largest in the ancient world up to that time and the Assyrian concept of God would influence later monotheistic visions of the divine.

Mesopotamia continued as a diverse and innovative region until the 7th century CE when it was conquered by the Arab Muslim invaders who afterwards mandated religion and cultural traditions. As with ancient Persia, indigenous belief systems and traditions were initially outlawed but later assimilated into the culture of the conquerors. For those who know the history of Mesopotamia, the region commands the highest respect as the source of many of the most enduring aspects of world culture.

Ancient Mesopotamia 101 | National Geographic

Bibliography

Bertman, S. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Black, J. , et. al. The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press, U.S.A., 2006.

Bottéro, J. Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Dalley, S. Myths from Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Jonker, G. The Topography of Remembrance: Mesopotamian Naru Literature. Brill Publishing, 1995.

Kramer, S. N. History Begins at Sumer. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988.

Kramer, S. N. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press, 1971.

Kriwaczek, P. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. St. Martin's Griffin, 2012.

Leick, G. The A to Z of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press, 2010.

Mitchell, S. Gilgamesh. Atria Paperback, 2020.

Van De Mieroop, M. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC, 2nd Edition. Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Von Soden, W. The Ancient Orient: An Introduction to the Study of the Ancient Near East. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language! So far, we have translated it to: Portuguese, Spanish, Arabic, Greek

About the Author

Joshua J. Mark

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1600/ten-ancient-mesopotamia-facts-you-need-to-know/