Portuguese Goa

Basilica of Bom Jesus, Goa

Goa, located on the west coast of India, was a Portuguese colony from 1510 to 1961. The small coastal area was conquered by Afonso de Albuquerque (c. 1453-1515) and became an important trade hub for the Eastern spice trade. Goa was the capital of the entire Portuguese Empire east of the Cape of Good Hope for 450 years.

The Viceroy of Portuguese India resided at Goa, and ships from the port sailed across the empire from East Africa to Japan bringing in horses, spices, slaves, and other goods which could then be traded in other Asian ports or sent back to Lisbon. The population of Goa was composed of a minority of Europeans, a large number of mixed European-Asians, and by far the majority, Hindu farmers. The city, now known as Old Goa, moved 10 km (6.2 mi) east in the 17th century and became known as New Goa (aka Panjim, now Panaji). The city, along with the rest of the empire, went into decline following attacks by the Dutch and the English which severely restricted Portuguese trade and revenues. Goa achieved independence in 1961 and became a state within the Republic of India in 1987.

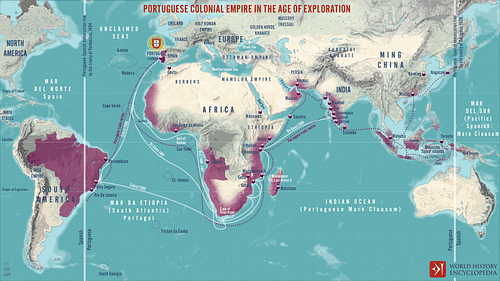

The Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Crown colonized with success three uninhabited archipelagoes: Madeira (1420), the Azores (1439), and Cape Verde (1462) in the Atlantic off the coast of West Africa. These were the first stepping stones in a series of maritime explorations that sought to sail down the coast of West Africa and reach Asia by sea.

A FORT WAS SOON BUILT TO MAKE SURE THE PORTUGUESE KEPT HOLD OF THEIR PRIZE, VALUED FOR ITS STRATEGIC POSITION WITHIN THE ASIAN TRADE NETWORK.

In 1497-9 Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa, up the coast of East African, and crossed the Indian Ocean to arrive at Calicut (now Kozhikode) on the south-west coast of India. Thus a direct sea route from Europe to Asia was discovered, and the Portuguese could now bypass the Middle East land and sea trade routes, which were controlled by Islamic states. Further, it was hoped that there might well be Christian states in Asia that could become useful allies in Christianity’s ongoing battles with the Islamic caliphates. Additional motives for colonization were to find new resources of precious goods like gold, develop new agricultural lands, and win prestige for the Crown and those who voyaged the high seas.

Portuguese Colonial Empire in the Age of Exploration

Other and larger expeditions followed da Gama’s as the Portuguese attempted to monopolise the Eastern spices trade, which had been prospering across Asia for centuries. Partially successful in this endeavour in the first half of the 16th century thanks to their superior ships and cannons, the Europeans set up their headquarters at Portuguese Cochin (now Kochi) further down the coast from unfriendly Calicut. From the west coast of India, the Portuguese went even further east.

Francisco Serrão sailed to the Spice Islands (aka Maluku/Moluccas Islands) in 1512, and Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521) made the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519-22. A string of colonies was soon established, particularly lustrous pearls being Malacca in Malaysia, Colombo in Sri Lanka, Macau in China, and Nagasaki in Japan. First Cochin and then Goa became the hubs for this many-spoked empire of trading posts and fortresses. In 1505, King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495-1521) appointed the first Viceroy of India, Francisco d’Almeida. The idea that the Portuguese could actually control Asia was an overly ambitious one, but from the outset, the intent was there, not to colonise land or peoples, but to monopolize trade.

The European Takeover

Goa was a port with a turbulent history in the second half of the 15th century. It was first part of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire, and then, following the conquest of 1472, it became a part of the Muslim Bahmani Sultanate. Just prior to the Portuguese arrival, the Bhamani Sultanate broke up into a number of successor states. The state which then ruled Goa was Bijapur. The city was conquered from local rulers in 1510 when a force led by Afonso de Albuquerque seized the port. Albuquerque was the viceroy (1509-1515), and he gained valuable inside knowledge of the enemy thanks to the assistance of Timmayya (aka Timoja), a Hindu adventurer. The Muslims fought back and recaptured the town within three months, but Albuquerque returned with a large fleet of warships and conquered Goa for a second time. This time it was for keeps, but thousands of civilians had died in the conflict. The view from the Indian side of these events, and the life of Goa in subsequent centuries, is not documented in any detail in Indian sources. The Europeans are mentioned here and there in the local historical record but usually only to comment on their odd dress and behaviour.

Afonso de Albuquerque

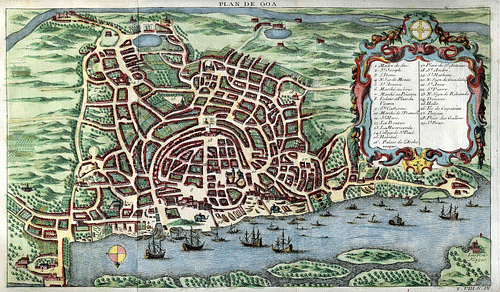

Geography

A fort was soon built to make sure the Europeans kept hold of their prize, valued for its strategic position between the trade going on in Gujarat to the north and the Malabar Coast to the south. The area controlled by the Portuguese was actually a number of islands situated in the maze of waterways created by the outflow of the rivers Tissuari and Zuari. These waterways made defence from inland attacks relatively easy. There were two good deep-water ports, although one was not operable during the monsoon season (June to September). Although there was some land suitable for agriculture, contact with the interior, still controlled by the Bijapuri, was limited, and for most of its existence, the colony remained dependent on imported foodstuffs.

THE EUROPEANS DIVIDED THEMSELVES INTO THREE CLASSES: EUROPEANS, EUROPEANS BORN IN THE COLONIES & MIXED-RACE EUROPEANS.

Society

The population of Goa before the European conquest is not known. The first few hundred Portuguese settlers, over the next few decades, became a population of nearly 2,000 households which included Europeans and mixed European-Indian families. By the mid-16th century, there were some 4,000 Portuguese (and other European settlers like Italians, French, English, and Flemish), 10,000 converted Indian Christians, and at least 50,000 mostly Hindu Indians. By 1600 the population was around 75,000, and by the 1630s perhaps 250,000. For comparison, the city of Delhi had a population of around 500,000 and Lisbon around 100,000 in the early 17th century. Goa might have been even bigger if not for the high mortality rate on foreigners from diseases like cholera and malaria.

The city was much like any other in India under Portuguese rule with a surrounding defensive wall, a fort, governor’s residence, bazaars, various quarters of accommodation based on religion and occupation, a maze of small winding streets, and one significant boulevard, the Rua Direita. Churches were built and other European-style buildings, although those seen today date to the 17th century. Initially, both Christian and Hindu religious festivals were held, but from 1540 religious intolerance grew, and the Inquisition arrived from Europe in 1560. Consequently, temples were destroyed, all Hindu ceremonies, including marriages and cremations, were banned, and even types of traditional clothing and foodstuffs were prohibited. Unsurprisingly, success in converting the population to Christianity was limited. Reforms and the end of the Inquisition in 1774 saw a more tolerant attitude to non-Christians, a policy largely driven by the territorial expansion of Goa in the mid-18th century which brought many more Hindus within the governance of the city.

Christian organizations had a significant presence in the colony as the Portuguese sought to convert the locals. There were some 70 churches and a large number of monasteries and convents. The Jesuits created an educational foundation, the largest such college in Asia, and they ran the royal hospital (although its mortality rate was appalling). The Misericórdia brotherhood had a branch that offered some essential social welfare services, too.

As one would imagine in a colony, the Europeans had the highest status and social display was commonly achieved through extravagant clothing and the number of servants and armed men one had in tow. The Europeans divided themselves into three classes: Europeans, Europeans born in the colonies, and mixed-race Europeans. On top of this were another four layers based on membership of the nobility, clergy, army, and all others (subdivided into the married and unmarried). There were also visiting Europeans such as maritime traders and Muslim merchants from other ports in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

The next level down from the Europeans was composed of the local people who had adopted Christianity, and then there was everyone else, that is, the majority of the population who were mostly Hindus and who spoke Konkani. The Hindus had their own age-old societal structure, which was topped by the brahmins. Gujarati traders were another significant group outside the European social structure.

There was contact between these groups, intermarriage as mentioned (there were very few European women in Goa) but also in everyday life where Hindu doctors were employed by settlers, local women lived with Europeans as concubines, and local artists were employed to paint religious scenes for the interiors of churches or even paint official portraits of viceroys. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that much like in other European colonies, pure white Europeans held on to the real power in Goa, even if in many ways village life continued as it had for centuries. At the bottom of society were the slaves, most of whom came from Mozambique. Slaves were another status symbol for the European settlers with the wealthiest having as many as 300, while a typical artisan might have 20.

Capital of the Portuguese Indies

In 1530, 20 years after it had been established, Goa replaced Portuguese Cochin as the administrative capital not only of Portuguese India but the Estado da India, that is (in its widest meaning) all Portuguese colonies east of the Cape of Good Hope. Officials in those parts of East Africa and Japan controlled by the Portuguese, for example, took their orders from the viceroy of Goa. In the 17th century Goa, along with a handful of other colonies, was permitted to send representatives to sit in the Portuguese parliament, the Cortes.

Map of Goa, c. 1750

At Goa, the viceroy was effectively both the civil and military governor of the Estado da India, and he was, in theory, accountable only to the king. Religious affairs were led by a bishop based at Goa (from 1538, then an archbishop from 1560), with the first cathedral built in 1539. The massive Cathedral of Santa Caterina was built between 1562 and the 1630s. Legal matters were the responsibility of a High Court with Portuguese as the official language. European-style laws were only applied to the European or mixed-race populations, and Hindus were left to use their own traditional legal mechanisms. Local villages were left to rule themselves in most matters as they had always done.

SO IMPORTANT WAS THE HORSE TRADE TO GOA THAT SHIPS BRINGING TEN OR MORE ARABIAN HORSES WERE GIVEN EXEMPTION FROM CUSTOMS DUTIES ON THE REST OF THEIR CARGO.

A captain led the military force of Goa, which resided in the fort and numbered around 500 men at certain times of the year. A factor was responsible for royal trade and extracting the lucrative customs duties from other types of trade. The viceroy was assisted by a ruling council, but in the first half of the 16th century, this was an informal body called whenever the viceroy needed specific advice, and its membership varied depending on the expertise required. Only from 1604 would a formal Council of State be formed. Each Portuguese colony, including Goa, had its own local council, which was elected by the Portuguese and Eurasian citizens of the European settlement. Finally, Goa had its own mint and was the first Portuguese colony to hammer out its own silver coins.

Trade to & from Goa

Goa, then, was the heart of the Portuguese Empire in the East, and the docks welcomed goods of all kinds but especially precious spices like pepper, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, and cinnamon. These spices were in huge demand in Europe and commanded very high prices. Goods exchanged for spices from India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and South East Asia included Indian-made cotton goods, dry foodstuffs, and copper. Within Asia, spices and other goods were re-exchanged for gold, silver, fine textiles, and rice. Crown-licensed ships plied their trade goods between Goa and Lisbon, Goa and Portuguese Macao, Goa and Portuguese Nagasaki, and Goa to Portuguese Mozambique.

Other important trade goods included horses from the Persian Gulf, around 1000 a year at the trade’s peak in the mid-16th century and mostly destined for the sultans of the Deccan in southern India. So important and lucrative was the horse trade to Goa that ships bringing ten or more Arabian horses were given exemption from customs duties on the rest of their cargo, even a cargo of five horses earned some tariff reductions. Goa was also the region’s foremost centre for diamonds, which came from southern India, a position it would hold until the 18th century and the rise of British-controlled Madras (now Chennai) on the eastern coast of India.

Portuguese Carrack Ships

The Portuguese attempted to impose a monopoly on Indian Ocean trade, particularly spices. Traders caught without a license or a Portuguese passport (cartaz) were arrested and their ship and cargo were impounded; many Muslim traders were executed. Those permitted to trade were often only allowed to do so on a restricted basis such as dealing in one spice only and then in limited quantities. Often passports were valid for two ports only. Customs duties had to be then paid at the destination port. To limit illegal trade, ships were often obliged to travel in Portuguese-controlled convoys (cafilas) and only to sail to selected ports like Goa. Consequently, customs duties made up around 60% of the entire Portuguese revenue in the East.

Threats From Other Powers

By the 17th century, relations were mostly friendly or neutral with the neighbouring Bijapuri sultans, but the Portuguese were careful to maintain their technological advantage in weaponry. In 1620, when one Portuguese expert in casting cannons attempted to sell his expertise to the sultan, the viceroy of Goa sent an assassin to make sure the defector’s knowledge died with him.

From the early 17th century, other European powers now wanted to directly involve themselves in the Eastern trade bounty, notably the Venetians and the Dutch. The Dutch arrived in Southeast Asia in 1596 and from there steadily took over many Portuguese trading centres such as Malacca (1641) and Colombo (1656). They took over Cochin in 1663 after a four-year siege. Dutch attacks on Goa were repulsed in 1603 and 1610, but they then blockaded the islands from 1638 to 1644. Goa held out.

Portugal was struggling to police the vast spread of its empire, and many forts suffered from a lack of upkeep making them relatively easy targets. Then there was a costly war with Spain from 1640 until 1668 and the Dutch attacks on Portuguese Brazil. Defeated in South America, the Dutch again turned their attention to the East and blockaded Goa for a second time from 1656 to 1663, when a peace treaty between the two European nations was finally signed. By this time, the Portuguese had only five forts besides Goa left in India. Goa had withstood the siege thanks to foodstuffs coming in from further along the coast by small boat. The Hindu Marathas, who controlled central-western India around Goa were a threat from the mid-17th century. They attacked Goa directly in 1698 and were another severe disruption to Portuguese trade.

Cathedral of Santa Caterina, Goa

Trade at Portuguese Goa never really recovered its former glory. There was a rising competition from the Middle East land and sea routes to take goods to Europe. In addition, the Dutch and English set up highly efficient trading companies in Asia. All of these factors conspired to diminish the trade revenue of Goa and other Portuguese centres. The site, now referred to as Old Goa, went into decline and was abandoned. A new settlement was created 10 kilometres to the east, New Goa (now Panaji), which prospered and became the capital of the Estado da India in 1827. The main reason for the move seems to have been the poor quality of the local water which caused an intolerable rise in the already high deaths from cholera and malaria.

The new settlement was not without its troubles, and during the Napoleonic Wars, it was occupied by the British from 1799 to 1815. The British were concerned France might gain the port; after the war, they even offered to buy it from the Portuguese government but were turned down. By now Goa was a colonial backwater that only made the news when riots broke out over racial equality laws or misguided and unsuccessful attempts by some governors to impose the Portuguese language and ban Konkani. In the mid-20th century, Portugal made a last grab at Goan resources, as iron ore and manganese mining were finally developed, but none of this new wealth went to the ordinary people. Finally, in 1961, following a decade of diplomatic pressure from a now free India, Goa was occupied by the Indian army, and it met little resistance. Portuguese rule, which had outlasted most other colonial powers in the region, finally ended. In March 1962, Goa was formally incorporated into the Indian Union, and in 1987, it became one of India’s smallest states. Very little remains of the Portuguese presence in Goa architecturally speaking, except for a handful of churches and the two great buildings of the Cathedral of Santa Caterina and the Basilica of Bom Jesus.

Réflexion sur l'héritage portugais de Goa

Bibliography

Cliff, Nigel. The Last Crusade. Harper Perennial, 2012.

Disney, A. R. A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Disney, A. R. A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Oliver, Roland. The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Pearson. New Cambridge History of India Volume 1 . Cambridge UP, 2021.

Russell-Wood, A. J.R. The Portuguese Empire, 1415-1808. JHUP, 1998.

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE

https://www.worldhistory.org/Portuguese_Goa/