Portuguese Angola

Queen Nzinga of Matamba

Portuguese Angola in southwest Africa was the first European colony on that continent. While settlement from 1571 proved problematic in the interior, the Portuguese did obtain a large number of slaves which they shipped to their Atlantic island colonies and to Portuguese Brazil right up to the end of the Atlantic slave trade in the 19th century.

With the capital at Luanda on the coast, the Portuguese struggled against the kingdoms of Kongo, Ndongo, and Matamba to gain control of the interior. The Angolan Wars saw shifting tribal allegiances thwart the relatively small number of Afro-Portuguese, but help from Brazil, eager to maintain the flow of slaves, proved crucial. The decolonization process in the mid-20th century was one of the most bloody and shambolic in Africa, and civil war continued long after independence was gained in 1975.

The Portuguese in West Africa

The Portuguese arrived in West Africa, and from the late 15th century they began to explore further south. Following the Portuguese colonization of São Tomé and Principe in 1486, the Europeans were looking for slaves to work on their sugar plantations. The Portuguese settlers on São Tomé and Principe had already been in trade contact with the mainland, searching for gold, pepper, and ivory. The main trading partner was the Kingdom of Kongo (c. 1400 - c. 1700), which controlled a booming regional slave trade. Through the 16th century, slaves from Kongo (and also the Kingdom of Benin) were transported to the Portuguese islands and to their colonies in the North Atlantic like Madeira.

A FORCE LED BY PAULO DIAS DE NOVAIS SECURED THE FIRST EUROPEAN COLONY IN AFRICA IN 1571.

The Portuguese had bought African slaves with cotton cloth, silk, mirrors, knives, and glass beads, but they got the idea to launch their own slave-capturing expeditions in Africa’s interior and cut out the Kongolese middlemen. The Kongo kings were not pleased with this development, and they were increasingly alarmed at the effects of European culture and the Christian religion on their subjects. As relations soured, the Portuguese began to look for another trade partner further down the coast of Africa.

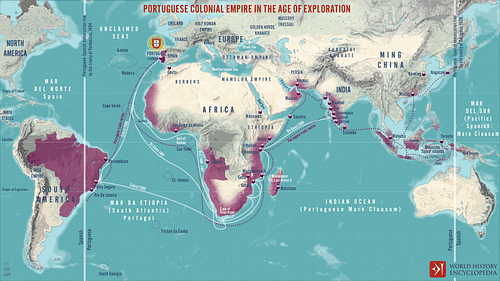

Portuguese Colonial Empire in the Age of Exploration

Exploring further south in the mid-16th century, the Europeans came into contact with a new kingdom, or rather a loose confederation of Kimbundu tribes, then known as Ndongo, probably formed c. 1500. Its ruler was called the Ngolo, which derives from the local word for iron - ngola - and from which the name Angola derives. The Portuguese attempted to create a new slave industry partnership with Ndongo and even involved the kingdom in a war with their northern neighbours, the Kingdom of Kongo. Ndongo had already defeated Kongo in a battle in 1556 and so seemed a good candidate to satisfy Portugal's ambitions in the region.

Foundation: Paulo Dias de Novais

Angola covers a region with dry woodlands in the south and grassland savanna in the north, which, thanks to its suitability to agriculture and pastoralism, was settled from the Early Iron Age. There were (and still are) problems caused by the irregular rainfall and the tsetse fly. The area had iron and salt mines which allowed the Angolans to trade with their neighbours. The royal capital was far inland, some 160 kilometres (100 miles) from the coast.

Although the first trade between Portuguese and Angolans was private, the Portuguese Crown soon got involved. An embassy in 1520 achieved nothing, but the Portuguese eventually returned. A 1559 embassy led by Paulo Dias de Novais with a number of Jesuit priests had no more success than the first try. Then, third time lucky, an expeditionary force led by Paulo Dias de Novais secured the first European colony in Africa in 1571. The Portuguese were able to gain control of the coast thanks to their superior weaponry.

Filippo Pigafetta, writing in 1591 and recording the memories of a Portuguese trader in the region, gives the following description of Angolan warriors:

On the head is a cap; crazily ornamented with the feathers of ostriches, peacocks, cockerels and other birds, which makes the men seem taller and very frightening. Above the waist they are entirely naked, but they have iron chains with rings the size of a man’s little finger, hanging down on each side to right and left, which they wear for military pomp and display. Below the waist they wear breeches of canvas or taffeta, and over them a cloth that reaches down to their feet, with the folds turned back and tucked under the belt. This belt, as we have said, is of exquisite workmanship, with bells attached to it…On their legs they wear boots similar to the laced boots of the Portuguese. We have already spoken of their weapons, which consist of bows, arrows, swords, daggers and shields.

(Newitt, 138-9)

Chokwe Sculpture, Angola

Dias de Novais was appointed the ‘lord proprietor’ of the new colony and given the responsibility of setting up a colonial government, building a fort, administering justice, and parcelling out land for development to the north and south of the River Cuanza. A governor was appointed by the Portuguese Crown in 1575. Way ahead of its time in terms of colonization in Africa, unfortunately for the Portuguese, the entire exercise was beset with failures and a century of fighting with indigenous peoples in what is often called the Angolan Wars. Indeed, Angola was to be forever a problematic colony within the Portuguese Empire until its independence.

Early Colonization

The first failed project was to establish white farmers near the coast. Too much rain and too poor soil put paid to that idea. An attempt to give white nobles huge estates in the interior also went badly. The Angolans forcefully resisted these land grabs. The Europeans had firearms, but these were still relatively primitive and in the country’s interior, they were greatly outnumbered by thousands of skilled bowmen, even if the Portuguese did get some aid from tribes eager to overturn the status quo. The search for mineral wealth was another failure with much time and effort was wasted on locating what turned out to be entirely mythical silver mines deep in the African interior. Even an attempt to control the salt mines of southern Angola proved beyond the limited number of Portuguese. A final disappointment was the attempt to spread Christianity, a religion the Angolans proved to be particularly indifferent to. The difficulties in Angola can be seen in the small number of Portuguese families attracted to the colony, most migrants preferred to try the seemingly healthier climate of Brazil:

In the 1660s the whole of Angola counted only 326 white households. By 1777 the white population was about 1,581, declining to about 1,000 in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

(Russell-Wood, 60-61)

There was one area that proved spectacularly successful for the Portuguese and made up for all the other disappointments. This was the creation of a small state in the west of the territory. Here, almost incredibly, a Portuguese army officer had managed to set himself up as a sort of local chief who received tribute from surrounding tribes. It was especially useful for gathering slaves for shipment out of Africa, and by the late-16th century, nearly 10,000 slaves a year were being exported from Angola. This trade devastated Angolan communities and agriculture and caused a migration of entire villages in all directions to get away from it. Another consequence of the European presence was the arrival of smallpox, first recorded in 1560 and which hit the population in devastating waves in subsequent centuries.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese began to slowly build up coastal settlements, starting with Luanda in 1576, and these became increasingly multicultural with Portuguese, Angolans, and Luso-Africans, as people of mixed Portuguese and African parents or ancestors are known. The Luso-Africans could speak both Portuguese and Kimbundu. There were, too, many undesirables (degredados) shipped by the authorities to Angola such as convicts, beggars, reformed prostitutes, orphans, and religious dissidents; many more than to other colonies because of the difficulty in attracting more desirable immigrants. At least as Angola became more established, there were also some immigrants from other Portuguese colonies, particularly São Tomé and Brazil.

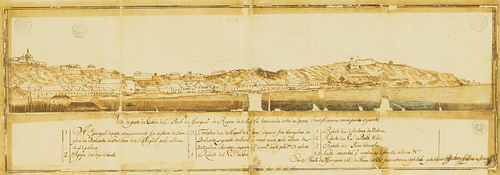

Luanda in the 18th Century

Luanda and Massangano (a key station in the interior at a major river junction) were fortified which was the reason they resisted a fightback from a confederation of Angolan tribes against Portuguese occupation in the first quarter of the 17th century. Luanda, in particular, had the mighty São Miguel fortress. The Europeans were helped by a group of marauding tribes, the Imbangala (Jaga), based in the Benguela Highlands, who attacked the Ndongo heartlands, forcing the king to flee in 1621. Sporadic fighting continued between various competing tribes and the Portuguese. Meanwhile, the new Kingdom of Matamba had risen from the ashes of Ndongo. In the 1620s and 1630s, Matamba was led by the formidable Queen Nzinga (l. c. 1583-1663) who resisted with great success any Portuguese attempt at the conquest of the interior of Angola.

MUCH OF PORTUGUESE ANGOLA BECAME A SLAVE FRONTIER WHERE WARS & KIDNAPPING SECURED THE SLAVES WHO WERE TAKEN TO THE COAST.

The Europeans were determined, and they now better combined their triple military advantages of cavalry, muskets, and artillery pieces. Just as the Portuguese were finally establishing themselves as masters of Angola, the Dutch arrived on the scene in 1641. Most of the region’s tribes, who had now been at war with the Portuguese for seven decades, sided with the Dutch against the Portuguese, and Luanda was taken. In 1648 reinforcements arrived from Portuguese Brazil - they were particularly keen to keep open the slave trade - and they took back Luanda. The Dutch surrendered and moved on to bother the Portuguese in other parts of their empire, but their occupation had driven the Portuguese to find slaves further south, devastating yet more communities in southwest Africa.

Tribal conflicts continued in the Angola region. In 1665, some Angolan tribes and Portuguese got together to defeat the Kingdom of Kongo at the Battle of Mbwila. The Europeans then suffered a reversal in a Kongo victory at Soyo in 1670. Civil wars then all but destroyed the Kongo state. The entire region saw the rise of different groups of traders who established not states but trading communities and networks of alliances. In 1676 a bishop was appointed at Luanda who now oversaw the see of São Salvador do Congo. In 1683 peace was finally agreed with the Matamba Kingdom. The Angolan Wars were finally over, and trade, on a larger scale than ever before, replaced warfare.

The 18th Century

From 1700, the Portuguese lost control of the slave trade in the area north of Luanda to the Dutch, English, and French and so they concentrated on the area south of Luanda and as far inland as the Zambezi River. Luso-African settlements now included the important coastal city of Benguela while other settlements sprang up in the interior in the Benguela highlands. Unlike in other colonies, mixed-race people rose to the highest political and administrative positions. Within Angola, there also existed a sizeable area of small independent kingdoms collectively known as the Ovimbundu kingdoms. Linking the interior to the coastal areas were trails used and maintained by Luso-Africans who, known as sertanejos (‘backwoodsmen’), traded, managed trade caravans, prospected for minerals, and offered their services as soldiers to tribal chiefs.

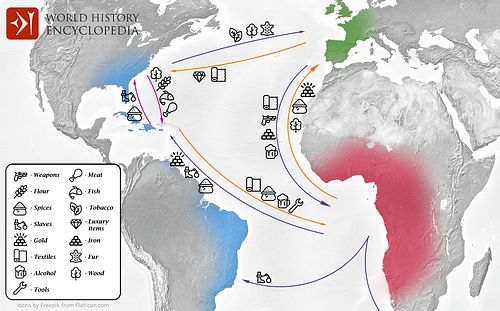

Transatlantic Triangular Trade Map

The Atlantic Slave Trade

From the mid-16th century, when sugar production on São Tomé and Principe declined due to Brazil dominating that industry, the islands became a hub in the trade network that shipped African slaves to Europe, North Africa, and across the Atlantic to the Americas, particularly the Spanish Caribbean and Brazil. The islands acted as a gathering point for slaves and as a place to take onboard provisions for the ships which would carry the human cargo.

Brazil was by far the largest importer of slaves in the Americas throughout the 17th century. When Brazilian sugar production was at its peak from 1600 to 1625, 150,000 African slaves were brought across the Atlantic, and most of these came from Guinea and Angola. The interior of Angola, in particular, became a slave frontier where wars and kidnapping secured the slaves who were taken along established trade routes to the coast. The area was severely depopulated as a result. Manioc plantations were established to feed the slaves and their keepers as they crossed the country. At the ports, slaves were assembled in slave barracks known as barracoons at Luanda and Benguela. Many died before they even met the ordeal of the transatlantic trip to Brazil.

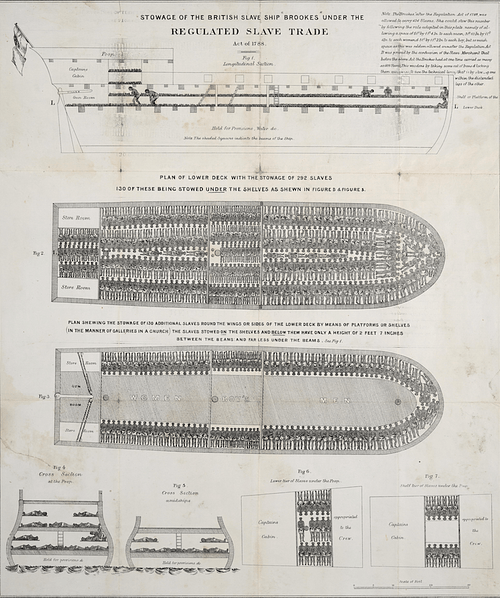

In the entire history of the Atlantic slave trade, around one-third of all slaves went in Portuguese ships to Brazil and for resale to Spanish colonies, some 3 million slaves. One in five of these slaves never survived the horrendous conditions of transportation onboard cramped, filthy ships. The two colonies of Brazil and Angola conducted direct trade with each other, the former sending goods like cane brandy (cachaça/jeribita) in Brazilian-owned ships in exchange for slaves acquired by the Angolans.

Diagram of the Stowage of Slaves on a Slave Ship

Slave Trade (Public Domain)

Post-Slave-Trade Angola

It was only towards the end of the 19th century that Portuguese Angolan settlements widened away from the coastal strip (only about 150 km or 93 miles wide) to occupy the area more or less covered by the modern state today. Following the independence of Brazil (1822), 497 Portuguese immigrants arrived in Angola from South America between 1849 and 1851. For a while, the Portuguese had entertained hopes of moving east and linking up with Portuguese Mozambique on the other side of the continent, but the British, moving up from South Africa, ended that particular ambition.

Portuguese-British treaties in the first quarter of the 19th century prohibited the slave trade in the region, which accounted for 90% of Angolan exports and 85% of government revenue. Unsurprisingly, many slave traders ignored the treaties. The authorities cracked down on the trade in the 1840s, but it was really the abolition of the slave trade by Brazil in 1853 that finally put an end to the transatlantic trade. From the early 19th century, cacao and coffee were grown with some success on the islands of São Tomé and Principe, with the former crop still dominating today. Slaves continued to be imported from the mainland to work these plantations, and this was not prohibited until 1908.

Following the end of the slave trade, half of the Europeans in Luanda left. There was still some illegal slave trading going on, but from 1860, the bonded labour market had taken over along with a boom in ivory exports and wax. In the interior, where wealthy independent merchants and plantation owners had no reason whatsoever to listen to the proclamations of people in the coastal cities, slavery went on as before until around 1911 when famines did more than anything to put a stop to it. Even in the 20th century, when African labourers from Angola and Portuguese Mozambique had to be repatriated after a certain number of years, the living conditions were little different from those their slave predecessors had had to bear.

Another export of Portuguese Angola in the second half of the 19th century was foodstuffs grown on plantations such as coffee, cotton, groundnuts, and sugar. Rubber became another important local product. The rise in legitimate trade rescued places like Luanda from a period of serious decline.

The Portuguese were not always in full control of their colony with serious uprisings in 1902 in the central Bailundu region, in 1907 in the Ndembu chiefdom near Luanda, and in 1913 the remnants of the old Kongo Kingdom rebelled. These were all put down eventually, and the Kongo region was absorbed into the colony. The Kwanyma tribe in the southern area which bordered Namibia continued to resist colonial control, and only a bloody war in 1915 subjugated them. In the 1920s, when diamonds were first discovered in northeast Angola, more unrest occurred in what was undoubtedly Portugal’s most difficult colony to govern.

The War of Independence

Angola became an Overseas Province of Portugal in 1951 and gained full independence as the People’s Republic of Angola in 1975. Decolonization had been a long and bloody process, mostly because the Portuguese government, then a military dictatorship under António de Oliveira Salazar (ruled 1932-1968), refused to see the inevitability of independent African states. Further, the Portuguese government, for reasons of prestige and an absence of democratic opposition, was able to spend around half of its annual budget on military escapades in Africa. There was also the consideration that by granting independence, the Portuguese would lose any future trade benefits with former colonies since the European state was itself impoverished and had little to offer them. It was more than likely that other powers would step in and dominate relations with such new and independent states as Angola and Mozambique.

Salazar did get support in his colonial policy from the USA, eager to maintain their military base in the Portuguese Azores, and from other western powers and investors who wanted to see a white-dominated South Africa protected from the rest of black Africa. Salazar thus had the international backing and funding to send Portuguese troops to fight a futile war from 1961 to hold on to Portuguese Angola. It was a conflict that only the war in French Algeria matched in terms of brutality, but there was, ultimately, the same result: independence.

Following Angolan independence in 1975, civil war erupted as various groups, each supported by foreign powers, battled for control of the country. In 1992 the official name of the country was reduced to the Republic of Angola. After various failed peace treaties, the United Nations sent a peace-keeping force in 1995, but the country has achieved relative stability since the end of the civil war in 2002.

Bibliography

Disney, A. R. A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

McEvedy, Colin. The Penguin Atlas of African History. Penguin Books, 1996.

Newitt, Malyn. The Portuguese in West Africa, 1415–1670. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Niane, DjiBril Tamsir. UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV. University of California Press, 1984.

Ogot, B. A. UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. V, Abridged Edition. University of California Press, 1999.

Oliver, R. A. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa . Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Oliver, Roland. The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Philip Curtin & Steven Feierman & Leonard Thompson & Jan Vansina. African History. Pearson, 1995.

Russell-Wood, A. J.R. The Portuguese Empire, 1415-1808. JHUP, 1998.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language! So far, we have translated it to: French

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Portuguese_Angola/