Thomas Cavendish

Thomas Cavendish

Thomas Cavendish (1560-1592 CE) was an Elizabethan mariner and privateer who famously circumnavigated the globe in 1586-88 CE, only the third voyage to do so and the first to set sail with that specific intention. Returning rich from Spanish treasure and basking in the glory of his feat, Cavendish set off to repeat the voyage and also find the Northwest Passage in 1591 CE. Beset by storms and unable to round the tip of South America, Cavendish's ship was obliged to turn for home, and he died at sea in May 1592 CE.

Early Career

Thomas Cavendish was born in Suffolk in 1560 CE to a wealthy family and, when he came into his inheritance, he seemed set up for a life of ease. However, Cavendish's lifestyle of high-spending soon exhausted his funds. The life of a mariner and privateer on the high seas then appealed, and Cavendish mortgaged his remaining property to join an expedition organised by Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE) in 1585 CE. Cavendish captained one of the fleet's ships, the Elizabeth, on this second voyage to establish a colony in North America in the area Raleigh had named 'Virginia' after his queen, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE). Returning to England, Cavendish, with only one voyage as experience, now sought to lead his own expedition.

Circumnavigation

After the voyages led by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521 CE) in 1522 CE and the Englishman Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) in 1580 CE, Thomas Cavendish would be the third to circumnavigate the globe. Unlike his predecessors, though, Cavendish set out with that specific objective and he prepared himself well for the challenge by learning about the latest theories of navigation from such figures as the noted astronomer and mathematician Thomas Harriot (c. 1560-1621 CE). He also gathered together as many charts as he could find and recruited a number of men who had sailed with Drake on his circumnavigation.

ONE SHIP, THE HUGH GALLANT, WAS DELIBERATELY SUNK ON 5 JUNE AS THERE WERE NOW INSUFFICIENT MEN TO SAIL IT.

Cavendish's fleet of three ships was composed of his flagship the Desire (140 tons), the Content (60 tons) and the Hugh Gallant (40 tons). The trio set off from Plymouth harbour on 21 July 1586 CE. Following one of the established routes to the New World, Cavendish sailed along the coast of Africa, passed the Canary Islands, and moved on down the west coast of Africa to what is today Sierra Leone. Attacking an indigenous village and pausing to restock at the Cape Verde Islands, Cavendish crossed the Atlantic Ocean to reach the coast of Brazil by the end of October. Here, the expedition resupplied and refreshed for three weeks on the coastal island of San Sebastian. Cavendish even had a pinnace built, a small vessel useful for exploration in shallow coastal waters.

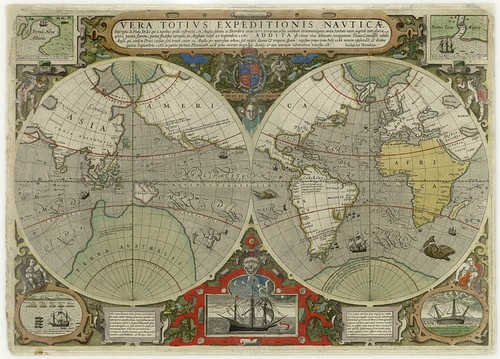

Map of Drake's and Cavendish's Circumnavigations of the Globe

Voyaging on down the coast of South America, the explorer discovered a large and favourable harbour on the coast of Patagonia, which he named Port Desire on 17 December. He then sailed to the southern end of the continent and, on 6 January 1587 CE, began the passage through the dangerous Straits of Magellan, taking a tedious 46 days to do so. The length of this stage necessitated the crew feeding themselves on whatever they could find on the rocky coastline such as mussels, limpets, and wild birds.

JUST AS DRAKE HAD BEEN LEFT ALONE WITH THE GOLDEN HIND, SO CAVENDISH NOW COMMANDED ONLY THE DESIRE.

On 24 February, he was finally into the Pacific Ocean where, just as Drake had done a few years earlier, he raided Spanish colonial settlements like Arica and captured what cargo he could from Spanish ships. The expedition dropped anchors at Puma Island in the Gulf of Guayaquil (coastal Ecuador and Peru) to make essential repairs. Although Cavendish had steadily filled his ships with riches over the months, destroying some 19 ships, the price paid in the lives of his men was high. An attack by indigenous tribes at Guayaquil left 12 of Cavendish's men dead. One ship, the Hugh Gallant, was deliberately sunk on 5 June as there were now insufficient men to sail it.

Working his way up the coast of North America, Cavendish came across the greatest prize capture of the expedition. The carrack Great Saint Anna was on its way from Manila and was loaded with 22,000 gold pesos and 600 tons of precious silks and spices. It was sighted by Cavendish's men on 14 November off the coast of California and attacked over a period of six hours. The ship was personally owned by Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE) and so it was a double victory for the English privateer against his country's greatest enemy. Another useful addition was the knowledge of a captured Portuguese, one Nicolás Rodrigo, who was personally familiar with Chinese waters and possessed a map of that region. There was, too, another captive, this time a Spaniard, Tomás de Ersola, who knew the Philippines. This good fortune was counterbalanced by the splitting up of the expedition. Cavendish's second ship sailed for home as its crew had mutinied over what they considered an unfair division of the spoils from the Great Saint Anna. This ship, not at all living up to its name, was the Content. Seeing no point in continuing the voyage across the Pacific, the ship sailed for home but was never heard of again. Just as Drake had been left alone with the Golden Hind, so Cavendish now commanded only the Desire.

A Carrack Ship by Bruegel

Cavendish crossed the Pacific in a remarkably swift 56 days thanks to fine weather and with the help of the Equatorial current that sweeps across that Ocean from east to west. He landed at the Ladrones islands (today's Mariana Islands) on 4 January 1588 CE and then sailed to the Philippines in mid-January 1588 CE. Tomás de Ersola had intended to present a letter to the governor of Manila revealing that Cavendish was a privateer who had mugged the King of Spain's finest treasure ship, but his plan was discovered, and he was hanged. Working its way through the dangerous reefs, the Desire passed the Moluccas Islands, then Java, and was into the Indian Ocean by mid-March. Cavendish sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa in May 1588 CE. The privateer then turned explorer and stopped off to investigate the remote island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, the first Englishman to do so. St. Helena would become an important base for English privateers in the following years. Cavendish replenished the ship's stores and set sail for the homeward stretch of the voyage on 20 June.

Eleven weeks after leaving Saint Helena, and after weathering one final tremendous storm off the English coast, Cavendish arrived in Plymouth on 9 September 1588 CE. English privateers were not ones to miss an opportunity for a bit of dash and show. Cavendish had his ship decked out in damask sails and gold cloth, and all the crew wore silk as the Desire sailed into its homeport to show off the riches captured during the voyage.

The circumnavigation, which had taken 780 days, was a success. Cavendish had made himself and his backers a small fortune, and he was the toast of the court, even ballads were composed in his honour. There was no knighthood as there had been for Drake, but he was, after all, not the first but the second Englishman to sail around the world. However, coming right after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the voyage was another boost to national confidence, and it seemed that it was the destiny of Englishmen to rule the waves. Cavendish's epic voyage was recorded by one of his men, Francis Petty, extracts of which found their way into Richard Hakluyt's celebrated The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation, first published in 1589 CE.

Final Voyage

Cavendish next set his sights on finding the elusive Northwest Passage, that fabled stretch of waters in the frozen north that many hoped would connect the Americas to Asia and make a handy shortcut for trading ships carrying precious cargo from Asia to Europe. Many other expeditions, including three led by Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594 CE) in the 1570s CE, had explored the western coast of North America, and all had failed to find the Passage. This time, Cavendish teamed up with another famous mariner, John Davis (c. 1550-1605 CE) who himself had tried three times to find the Passage in 1585-87 CE. Naturally, sailing along the west coast of the Americas would necessitate a return home via the Pacific and another circumnavigation. It was hoped, too, that a few choice treasure ships of Philip's might be relieved of their cargoes along the way.

Accordingly, Cavendish and Davis, with their fleet of five ships, set off to round the bottom of South America. Cavendish commanded the Leicester Galleon, and Davis took the indefatigable Desire. Leaving England in August 1591 CE, the expedition reached the southern part of the Americas safely enough and lowered anchor at Port Desire.

They sailed down to the tip of South America but then, in March 1592 CE, a series of storms scattered the fleet in the Straits of Magellan. Mutiny, as so often the case in expeditions to these tempestuous waters, was thick in the air. At one point, Cavendish was even obliged to temporarily seek refuge from his crew by joining Davis on the Desire. The expedition leader seems to have been subjected to bouts of hallucinations in this period, perhaps caused by mouldy rye bread (causing ergotism, aka St. Anthony's Fire). As the weeks went by, the ships could not find their way through the straits and Davis and Cavendish became separated. While Davis made three more attempts at the Straits, Cavendish sailed for home. His supplies were dangerously low, and he then ran into a Portuguese ship in the Atlantic which attacked his vessel. Cavendish made it to Brazil, but before he could return to England, the circumnavigator died at sea in May 1592 CE, aged just 32. Davis, meanwhile, also turned for home, first discovering the Falkland Islands and then stopping off on the coast of Brazil. Davis finally made it back to Ireland but, after much privation, only 16 of his original 76-man crew survived with him.

19 - L'explorateur Thomas Cavendish et son tour du monde

Bibliography

Bicheno, Hugh. Elizabeth's Sea Dogs. Conway, 2014.

Elton, G.R. England Under the Tudors. Routledge, 2018.

Guy, John. Tudor England. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Wagner, John A. Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World. Checkmark Books, 2002.

Williams, Neville. The Sea Dogs. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1975.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Thomas_Cavendish/