Spanish Treasure Fleets

Spanish Galleon Under Attack

From the 16th to 18th centuries, two treasure fleets sailed each year, one to Mexico and the other to Central America, then part of the Spanish Empire. There they collected precious eastern goods and the riches of the Americas, including tons of silver from mines in Peru and Mexico. Known as the plate fleets, from plata (silver), the two convoys grouped at Havana, Cuba, before sailing back to Spain.

The Spanish galleons that carried this treasure and which protected other, similar vessels in the convoy were well-armed with cannons and packed with troops. Privateers, buccaneers, and pirates were sorely tempted by these floating treasure houses that carried in their holds more than the annual revenue of some European kingdoms. The convoy system, though, worked well, and with most enemies targeting the treasure ports instead, the greatest risk for the treasure fleets was to be wrecked by storms, treacherous currents, or hidden coral reefs.

From Spain to the Americas

From the first half of the 16th century, Spain was in control of much of Central and South America. From conquered peoples like the Aztecs, Maya, and Incas, the Spanish extracted whatever objects of value they could find, and they exploited silver mines in Mexico and Peru. The treasure fleets were the ships that brought this wealth back to Europe, riches which now belonged to the Spanish Crown, the colonial merchants who sent it to their partners in Europe, or the private investors of the fleets.

THE THREE MAIN TREASURE PORTS WERE VERACRUZ, PORTOBELO & CARTAGENA.

Each year from 1543, two different fleets of Spanish galleons and other ships sailed from Spain to the Americas. They were loaded up with coinage, bullion, high-value European manufactured goods, wine, olive oil, glassware, weapons, tools, clothing, books, papers, and a number of passengers. The fleets then crossed the Atlantic with this eagerly anticipated bounty destined for merchants and settlers in the Americas. The New Spain flota fleet sailed from Seville, usually in March-April, first to the Canary Islands and then across the Atlantic to arrive at San Juan on Puerto Rico. The fleet then hopped across to Santo Domingo on Hispaniola, on to Santiago de Cuba on the east coast of Cuba, and then arrived at Veracruz, Mexico. A different group, the Tierra Firme fleet, left Seville or Cadiz, typically in August-September, and sailed for Santa Marta and neighbouring Cartagena (in today's Colombia), and then Portobelo (in modern Panama) before returning to Cartagena.

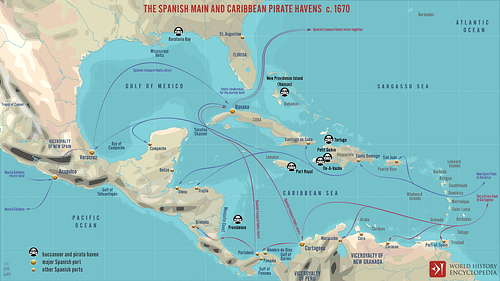

The Spanish Main and Caribbean Pirate Havens c. 1670

The Treasure Ports

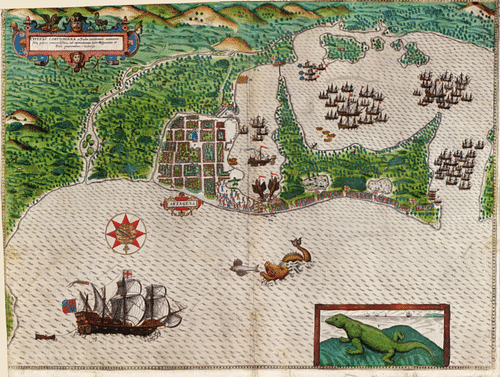

The treasure ports of the Spanish Main welcomed ships of the treasure fleets each year having stored up a mass of rich cargo ready for transportation to Spain. Most were heavily fortified to protect them from attack by privateers, buccaneers, and pirates of all nationalities. The three main ports were Veracruz, Portobelo, and Cartagena, but there were several others that the fleet called upon, the exact stops and sequence varying over the years.

Veracruz, founded in 1519, was protected by the fortress island of San Juan de Ulúa. It was the collection point for silver gathered from Mexico and the eastern precious goods brought by the Manila galleons (see below) to Acapulco and then transported across land to Veracruz. The treasure ships spent the winter in Veracruz before departing back to Europe.

THE SPANISH CROWN'S ANNUAL REVENUE ROCKETED FROM 35,000 DUCATS IN 1516 TO 2 MILLION DUCATS IN 1556.

Portobelo (aka Puerto Bello) on the isthmus of Panama was the collection point for silver taken from the Potosi mines in Peru which, at their peak around 1600, each year produced some 9 million silver pesos. The silver was sent by galleon to Panama on the western coast of the isthmus and from there overland by mule train to Portobelo (which had replaced Nombre de Dios in 1596). The English Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596) once described this corner of the Spanish Empire as "the treasure house of the world" (Cordingly & Falconer, 15).

Cartagena, founded in 1533, was a collection point for emeralds, pearls, gold, silver, and hardwoods from northern South America. It was known as the 'Queen of the Indies' (as the Americas were then known), and from 1614, thanks to its myriad of fortifications, it was all but impregnable. The Tierra Firme treasure ships spent the winter in Cartagena.

Muisca Double Eagle Pendant

The Manila Galleons

The Atlantic treasure fleets did not just carry the riches of the Americas, they also had in their holds precious goods from Asia. These latter were brought in another treasure fleet, the annual Manila galleons that were loaded up in Manila in the Spanish Philippines and which then sailed to Acapulco. The voyage was a testing one and took on average six months. The Manila galleons were in operation from 1565 to 1815. The Spanish themselves called them the naos de China or 'Chinese ships' as they carried high-value eastern goods. Some of the items were sold in trade fairs in Acapulco, but much of it was transported to Veracruz where it was eventually loaded onto ships of the flota destined for Spain. Once unloaded, the galleons returned to Manila carrying (on average) 3 million silver pieces of eight to buy new goods for the next trip to the Americas.

From Havana to Spain

Havana was the heart of the Spanish Main and the point where all ships in the two treasure fleets assembled through the spring before crossing the Atlantic back to Europe. Havana had a narrow harbour, easily protected by its massive fortifications, and from the mid-18th century, a garrison of 6,000 men and 180 cannons protected this jewel of the Spanish Empire. The two fleets typically set off in summer but did not always sail together. When they did sail together, each fleet still had its own commander. The ships usually arrived in Spain in October or November.

Treasure Fleet Cargo

Returning to Europe, the Spanish treasure fleets carried:

silver (coins and bullion)

gold (dust and bullion)

gems

pearls

hides

sugar

tobacco

cacao

tea

indigo

hardwoods

bales of llama wool

rolls of silk

Indian cottons

Persian carpets

spices

Chinese porcelain

medicines

perfumes

shells

quetzal feathers

live animals such as pumas, jaguars, parrots, and howler monkeys

American and Asian artworks and jewellery in precious materials

Headdress of Motecuhzoma II

Just how much treasure the Spanish were accumulating was kept a closely-guarded state secret, but the gilded cat was let out of the treasure bag as early as 1522. Jean de Fleury (aka Florin, d. 1527) led a fleet of eight ships and captured three Americas treasure ships off Cape Vincent. The French corsair feasted his eyes on three massive chests of gold bullion, 500 pounds of gold dust, 680 pounds of pearls, and cases of emeralds, as well as boxes stuffed full of Aztec art and religious objects made from all kinds of precious and exotic materials. There were even live parrots and jaguars. No wonder, then, that the Spanish Crown's annual revenue rocketed from 35,000 ducats in 1516 to 2 million ducats 40 years later. By 1600, 25,000 tons of silver alone had been transported to Spain.

Protecting the Fleet

A gigantic floating treasure chest was an obvious attraction for any rogue of the sea, but taking one was far from easy. Even in the pre-convoy early years, a Spanish galleon could present a formidable array of up to 60 cannons below and above deck, and they carried large crescent blades fixed to the yardarms, which were designed to cut the sails and rigging of any ship that dared get alongside.

A galleon was certainly far bigger and far better-armed than any pirate vessel and even most naval ships. Further, they had large crews and a contingent of professional soldiers led by a war captain. Passengers could put up a good fight, too. The elevated superstructures at the stern and bow of a galleon provided marksmen with an excellent platform above an enemy ship.

The ships were also very difficult to find in the open sea. This was particularly so for the Manila galleons which sailed alone – only four were ever captured in the relatively safer Pacific waters in over 250 years of service.

Spanish Conquistadores Being Tortured

From 1555, following an idea instigated by Captain-General Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, treasure ships travelled in large convoys with multiple warships for greater safety. Merchant ships, themselves armed with cannons, were additionally protected by a specific task force, the Armada de la Guarda de la Carrera de las Indias. This fleet of warships was created in 1521 to patrol the waters between the final stretch of the route, the Azores to Spain. It grew over the years to consist of up to 16 Spanish galleons. From the 1540s, the task force accompanied galleons all the way from the Caribbean to Europe, picking up the treasure fleet in Havana, sailing through the waters between Florida and the Bahamas, and then on back to Spain. If the treasure fleets were sailing back separately, the war galleons gave priority to the more valuable Tierra Firme fleet with its Peruvian silver (hence it acquired the name the 'Galleons Fleet'). At their peak, the fleet sailing from Spain had four warships as an escort while the treasure fleets returning to Spain could consist of up to 90 merchant vessels and at least eight warships.

The escort ships were funded by a shipowner's tax (averia) which was imposed on goods destined for the Americas. Those shipowners that wished to risk sailing without the escort were given harsh financial penalties. Further, a royal decree was issued to keep the ships in a tight formation within the convoy:

No ship may leave the convoy for any reason, not even to pursue an enemy sail. If ever a ship breaks this rule, her captain and navigator will each be fined 50,000 pesos and forbidden to sail to America for two years.

(quoted in Wood, 68)

Capture of the Nuestra Señora de Cavadonga

In effect, a galleon was a slow-moving but formidable castle on the sea. When in convoy, one 'castle' could give protective fire for another. The system worked well. There was additional protection provided by a roving fleet of warships in the Caribbean, the Armadas de Borlavento ("Windward Squadrons"). This was in service from 1578, first with two ships based at Cartagena and then with an additional two at Hispaniola and two more at Panama. These ships were often powered by both oars and sails so that they could better catch fast pirate ships.

Finally, there was always the option not to sail at all, as happened during all-out wars, for example, during the conflict between Spain and England from 1585 to 1603. In these periods, when the High Seas were especially dangerous, the treasure fleets skipped a year.

As a consequence of all of these defensive and strategic precautions, a treasure ship was far more likely to be sunk by storm, reef, or accidental fire than an enemy attack. Buccaneers like the Englishman Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688) and Dutchman Laurens de Graaf preferred to try their luck at the treasure ports, despite their fortifications. Still, there were some disasters for Spain through the years, but these do have the advantage of informing historians of what exactly treasures ships carried in their secret cargo holds.

Notable Captures

In March 1579, Francis Drake captured the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción (aka Cacafuego), a treasure ship which was taking 26 tons of silver bullion, 13 chests of plate, 80 lbs (36 kg) of gold, and a great many gemstones from Peru to Panama. The value of the cargo was at least 1.5 million ducats, more than many European kingdoms' annual revenue, and it made Drake the richest man in England.

Cartagena on the Spanish Main

The Manila galleon Great Santa Ana was captured by Thomas Cavendish (1560-1592) in 1587 and was carrying 22,000 gold pesos and 600 tons of precious silks and spices.

Around 1620, at least according to our only source, the famed author on buccaneers Alexander Exquemelin (1645-1700), the Norman pirate Pierre Le Grand (real name unknown) captured near Hispaniola no less a prize than the flagship of a Spanish treasure fleet. Le Grande's men had boarded the galleon during the night and taken the ship easily.

In September 1628, a Dutch force of 31 ships led by Admiral Piet Pieterszoon Hein (1577-1629) captured the entire New Spain treasure fleet on its way to Havana. Hein managed to seize 46 tons of silver and many other valuables. The capture was a sign of the times as Spain's naval power declined and that of Britain, France, and the Netherlands soared.

These successes and others were the exceptions, though. Much more usual was for a few smaller and less-valuable vessels to succumb to an attack when they had been separated from the main convoy, as happened in 1591 in the West Indies when a five-ship fleet commanded by William Lane captured two isolated vessels of the New Spain fleet.

The End of the Treasure Fleets

The quantities of loot extracted from the Americas declined from the 1620s, the mines in Peru producing less than a quarter of the silver by 1700 than they had been a century before. Conflicts like the War of the Spanish Succession from 1701 to 1714 severely disrupted the regularity of the treasure fleets. Nevertheless, the treasure ship convoys continued until the 1730s, with a small fleet continuing from Mexico alone between 1754 and 1789. Even if some single treasure ships continued to sail, by the mid-18th century, new trade centres had developed, and new commodities usurped the dominance previously held by silver, silk, and spices. The United States, Brazil, India, and China were the new big players, trading such lucrative goods as tea, opium, sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cotton in massive quantities worldwide.

Pieces of Eight from the Whydah

Treasure Fleet Wrecks

Many wrecks of Spanish galleons have been discovered, particularly in the Caribbean, and while few have yielded the treasure their discoverers had hoped, some have kept their precious cargoes intact. These archaeological sites are also an invaluable record of the treasure fleets and the daily life of the sailors who went down with them.

The Nuestra Señora de Atocha was carrying a cargo worth $400 million when it was wrecked in a storm in 1622 off the Florida Keys. The ship, built of mahogany, was discovered in 1985 by Mel Fisher. Down in the hold, its 20 tons of 70-pound silver ingots were still as neatly stacked as they had been over 350 years earlier. The ship also carried around one million silver pesos and a quantity of emeralds. The ship was typical of a flota vessel: 500 tons with a crew of 200 plus 90 soldiers and 50 passengers. The ship was armed with at least 24 cannons. Artefacts from the ship are now on display in Key West, Florida.

The Nuestra Señora de Encarnación sank during a storm in the Caribbean in 1681 off the coast of Panama. On its way to Portobelo, the ship was loaded with over 100 wooden chests containing ceramics, sword blades, mule shoes (for the Panama-Portobelo land route), and tools when it went down. The ship's finer cargo goods have long since perished with only the lead seals surviving to hint at what else might have been on board. The wreck site, discovered in 2010, has been excavated and surveyed by a team of marine archaeologists from Texas State University and provides an excellent insight into the construction of 17th-century Spanish ships.

The Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes was perhaps carrying 500,000 silver and gold coins when it was sunk by the British in 1804. The wreck site was disputed with competing claims for ownership of its riches coming from the private company that discovered it and the Spanish and Peruvian governments. Spain was finally declared the owner in 2012 by a United States federal court. It seems, then, the Spanish treasure ships are still as coveted today as they ever were in the days of the Spanish Empire.

Bibliography

Breverton, Terry. Breverton's Nautical Curiosities. Lyons Press, 2010.

Chartrand, René & Spedaliere, Donato. The Spanish Main 1492–1800 . Osprey Publishing, 2006.

Cordingly, David & Falconer, John. Pirates. Royal Museums Greenwich, 2021.

Giraldez, Arturo. The Age of Trade. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015.

Konstam, Angus & Bryan, Tony. Spanish Galleon 1530–1690 . Osprey Publishing, 2004.

Konstam, Angus & McBride, Angus. Buccaneers 1620–1700 . Osprey Publishing, 2000.

Rogozinski, Jan. Pirates!. Facts on File, 1995.

Wood, Peter. The Spanish Main . Time Life Education, 1980.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Spanish_Treasure_Fleets/