Causes of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (1337-1453 CE) was an intermittent conflict fought between England and France that started when king Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE) squabbled with Philip VI of France (r. 1328-1350 CE) over feudal rights concerning Gascony and trade with the Low Countries. Edward also asserted that he was the rightful king of France and pressed this claim by winning great victories at the battles of Crécy (1346 CE) and Poitiers (1356 CE). In 1360 CE, Edward renounced his claim to the French throne in return for lordship over a quarter of France. The war then continued as each side attempted to control north and southwest France. After Charles V of France (r. 1364-1380 CE) steadily regained much of the lands lost since the war began, there was a period of peace when Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE) married the daughter of Charles VI of France (r. 1380-1422 CE). Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422 CE), eager to win glory, booty, and legitimacy for his own reign, then reignited the conflict with his stunning victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 CE which enabled him to be nominated the heir to the French throne. After Henry V's untimely death and the ineffectual rule of Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71 CE), Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461 CE) retook the initiative. With help from such figures as the Duke of Burgundy and Joan of Arc (1412-1431 CE), Charles won the war and managed to remove the English from all French territory except Calais.

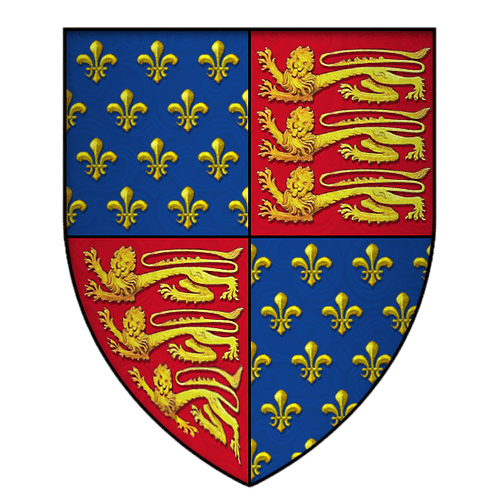

Coat of Arms of Edward III

The causes of the Hundred Years' War and reasons for its continuation include:

The seizure of English-held Gascony (Aquitaine, south-west France) by Philip VI of France.

The claim by the English king Edward III to be the rightful king of France.

The expedition of Edward III to take by force territories in France, protect international trade and win booty and estates for his nobles.

The ambition of Charles V of France to remove the English from France's feudal territories.

The descent into madness of Charles VI of France and the debilitating infighting amongst the French nobility.

The ambition of Henry V of England to legitimise his reign in England and make himself the king of France through conquest.

The determination of the Dauphin, future King Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461 CE), to regain his birthright and unify all of France.

Edward III vs. Philip VI

The English Crown had held lands in France ever since the reign of William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE) and the Norman Conquest of England from 1066 CE. However, by the 13th century CE, these lands had been much reduced with Normandy, Anjou, Maine, and Poitou all lost. Friction between the two countries frequently broke out into warfare, as during the reigns of Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307 CE) and Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314 CE). Edward III inherited such territories as remained but he was ambitious for much more.

EDWARD III WAS PERHAPS IRKED BY THE TECHNICALITY THAT, AS THE DUKE OF GASCONY, HE WAS ACTUALLY A VASSAL OF THE FRENCH KING.

Edward III was able to make a strong claim to the French crown via his mother Isabella. Whether or not this claim was a serious one or merely an excuse for invading France is still discussed today by historians. Certainly, on paper Edward did have a point. The current French king was Philip VI of France who had succeeded his cousin Charles IV of France (r. 1322-1328 CE) even if, when Charles had died, it was Edward who was his closest male relative, being Charles' nephew and the eldest surviving grandson of Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314 CE). The English king had not pressed his claim at the time because he was a minor, and the French nobility, discounting the legitimacy of inheritance through the female line, had naturally preferred a Frenchman as their ruler. However, by the mid-1330s CE Edward changed his strategy, perhaps irked by the technicality that, as the Duke of Gascony, the English king was actually a vassal of the French king according to the rules of medieval feudalism. Indeed, Edward had paid homage to Philip in Amiens Cathedral in June 1329 CE, most likely in order to avoid the French king confiscating the revenues of Gascony if he did not.

King Edward III of England

Another problem Edward faced was that France was allied with the old enemy Scotland which perpetually threatened northern England. Edward went so far as to identify Philip as a usurper, he refused to pay homage as a vassal, and also refused to hand over a political prisoner, Count Robert of Artois, as Philip had requested. When the French king confiscated Gascony to the French Crown in 1337 CE and raided the south coast of England the year after - an attack which included the destruction of Southampton, Edward was presented with the perfect excuse to start a war.

EDWARD DECLARED HIMSELF KING OF FRANCE IN A LAVISH CEREMONY IN GHENT IN JANUARY 1340 CE.

Gascony was worth fighting for because it had certain economic advantages. It was an important source of trade, receiving English grain and wool. The region was also the primary producer of the wine drunk in England. By making a claim for the French throne Edward could avoid a rebuke from the Pope for causing an unnecessary war. Further, the rich lands available in France could be used as a lure for baronial support in England, thus consolidating his position as king. Edward was no doubt ever-mindful that his own father, Edward II of England (r. 1307-1327 CE), had been murdered by ambitious barons. Captured nobles would be another handy source of revenue via ransoms. Edward may not have contemplated full occupation, but ravaging the French lands and stripping them of booty certainly was to show his intent, and in a typical piece of visual propaganda and pageantry, Edward declared himself King of France in a lavish ceremony in Ghent in January 1340 CE. In addition, the king henceforth quartered his coat of arms - the three lions of the Plantagenets - to now include the golden fleur-de-lis of France, which remained a part of the royal arms until 1801 CE.

Edward gathered together some valuable allies such as the Flemings of Ghent who similarly sought to relieve themselves from their feudal obligation to a French king but who needed English wool to make their primary export: cloth. Edward even bought the title of Imperial Vicar-General from Louis IV of Germany, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (r. 1328-1347 CE), which gave the English king imperial rights over the lords of the Low Countries. As with Gascony, Philip VI wanted Flemish wealth for himself and so he exercised his position as the feudal lord of the Flemish count, Guy of Dampierre to destabilise that region. On the other hand, in France itself there were those who were only too willing to take advantage of a distracted King Philip, these included Charles II, King of Navarre (r. 1349-1387 CE) and the Gascon counts of Armagnac amongst others. Edward was clever enough to use old grievances to effectively bring the decline of France from within and undermine its influence with its feudal vassals. As ever in the Middle Ages, a war led to opportunities for gains and losses in titles and lands amongst the nobility, all it needed was two monarchs similarly keen to fight.

Philip VI Presiding Over the Lawsuit of Robert of Artois

Edward could not have started his war with France better. In June 1340 CE a French fleet, probably intended to serve as a means to invade England, was sunk by an English fleet at Sluys in the Scheldt estuary (Low Countries). This was followed up in 1345 CE with the capture of Gascony, invasion of Normandy, and heavy defeat of a French army at the Battle of Crécy in August 1346 CE. The next year Calais was captured but the arrival of the Black Death plague interrupted the hostilities. The next major victory was another English one, once again against a much larger French army, this time at the Battle of Poitiers in September 1356 CE. King John II of France (r. 1350-1364 CE) was even captured at Poitiers.

Edward had enjoyed great successes but the campaigns were hugely expensive. Fortunately, in May 1360 CE the war seemed to have come to an end. In that year a treaty was signed between England and France, the Treaty of Brétigny. Edward's claim to 25% of France (mostly in the north and south-west) was recognised and, in return, he gave up any ambition for the French crown itself. John II, meanwhile, was released after his ignominious four years in captivity.

Charles V & the French Revival

From 1369 CE, the new French king, Charles V of France, aka Charles the Wise, began to grab back in earnest what his predecessors had lost by avoiding open battle and concentrating on harassment and relying on the safety of his castles when required. Charles also had a superior navy to the English and so was able to make frequent raids on the south coast of England. While Edward tried to raise yet more taxes on his financially oppressed people, Charles V's strategy brought dividends as he overran most of Aquitaine in 1372 CE, and by 1375 CE, the only lands left in France belonging to the English Crown were Calais and a slice of Gascony.

Relations improved with France on 12 March 1396 CE when Richard II of England married Isabella of France, the daughter of Charles VI of France. Isabella was only seven, but it was a union which cemented a two-decade truce between the two countries. The arrangement with Charles VI did not include Richard giving up his claim to the French throne and so the Hundred Years' War was, for now, merely put on hold. Under the next king, Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413 CE), the Crown was rather too preoccupied with English and Welsh rebels to do very much in France, although the Prince of Wales led a failed expedition there which seems to have whetted his appetite for further action once he became King Henry V in 1413 CE.

Henry V & Agincourt

Henry V was even more ambitious than Edward III had been, for he wanted not only to plunder French territory but permanently take it over and form an empire. For the king, success in war was also a useful tool in legitimising his reign, inheriting as he had the throne from his father Henry IV who had usurped the throne by murdering Richard II. Additional motivation came from the havoc caused by French pirates in the English Channel and the never-ceasing desire of English nobles to increase their estates and wealth.

Henry V was greatly helped in his ambitions on the Continent by the descent into madness of Charles VI of France and the consequent split in the French nobility between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians. Henry was also goaded by the heir to the French throne, Charles, the Dauphin who refused all diplomatic approaches and sent the young king a box of tennis balls with a note that he should concentrate on sports rather than war.

Henry invaded Normandy, captured the important port of Harfleur in 1415 CE and followed this up with a stunning victory at the Battle of Agincourt in October. By 1419 CE, Henry had managed to conquer all of Normandy. Victory at the battle of Agincourt made Henry V a national hero, and he made himself worthy of the accolade by marching on Paris in 1420 CE and obliging the French to sign a peace treaty with very generous terms. The English king was nominated as the regent and heir to Charles VI and, to cement the new alliance, Henry married Charles' daughter, Catherine of Valois (l. 1401 - c. 1437 CE) on 2 June 1420 CE in Troyes Cathedral. This was the apex of English success in the war.

Morning of the Battle of Agincourt

A condition of the Treaty of Troyes was that Henry had to promise he would continue fighting against the Burgundian's number one enemy: the now disinherited Dauphin Charles, thus perpetuating the Hundred Years' War for another round of conflict. As it turned out, Henry never got the chance to become the king of France as he died unexpectedly, probably of dysentery, in 1422 CE.

French Victory

The arrival of Joan of Arc in 1429 CE saw the beginning of a French revival as the Dauphin, now King Charles VII of France, took the initiative in the war. Henry VI of England had continued to press his family's claim for the French throne, eventually being crowned as such in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris in December 1431 CE but this was a sham without real substance. On 22 April 1445 CE, the marriage of Henry to Margaret of Anjou (d. 1482 CE), niece of Charles VII, indicated the English king's clear aversion to war with France.

The next crucial event was the defection of England's most important ally Philip the Good of Burgundy over to the side of the French king in 1435 CE. The weak rule of Henry VI then witnessed a second French revival. Charles VII was utterly determined and began to retake parts of Normandy from 1449 CE, he blockaded Bordeaux in 1451 CE and captured Gascony in 1452 CE. At the wars' end in 1453 CE and the French victory at the Battle of Castillon, the English Crown only controlled Calais. The French Crown then went on, by a mixed strategy of conquest and marriage alliances, to bring such regions as Burgundy, Provence, and Brittany together into one nation-state that was richer and more powerful than ever. A bankrupt England, meanwhile, descended into the insular dynastic squabbles that we today call the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE).

Bibliography

Allmand, Christopher. The Hundred Years War. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Blockmans, Wim. Introduction to Medieval Europe 300–1500. Routledge, 2017.

Cannon, John. The Kings and Queens of Britain. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Crouch, David. Medieval Britain, c.1000-1500. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Curry, Anne. The Hundred Years' War. Osprey Publishing, 2002.

Holmes, George. The Oxford History Of Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press, U.S.A., 2002.

Jones, Dan. The Plantagenets. Penguin Books, 2014.

Keen, Maurice. The Penguin History of Medieval Europe. Penguin Books, 1991.

Rothero, Christopher. Armies of Crecy and Poitiers. Osprey Publishing, 1981.

Saul, Nigel. The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval England. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Starkey, David. Crown and Country. HarperPress, 2011.

Wilson, Derek. The Plantagenet Chronicles 1154-1485. Metro Books, 2020.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language! So far, we have translated it to: French

About the Author

Mark Cartwright

Mark is a history writer based in Italy. His special interests include pottery, architecture, world mythology and discovering the ideas that all civilizations share in common. He holds an MA in Political Philosophy and is the Publishing Director at WHE.

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1517/causes-of-the-hundred-years-war/