Lubricant Empire: Chapters from the History of Palm Oil

This text is a translation of part of the book “ Palm Oil: The Lubricant of the Empire ” published by Pluto House in London in 2022, by Canadian researcher Max Haven , and includes extracts from the first three chapters of the book.

In recent years, there has been much talk about the destructive environmental dimensions of the palm oil industry, which is now included in a huge number of consumer goods, and about the miserable conditions of workers in this industry, particularly in Southeast Asia and West Africa and to a lesser extent in Latin America. But this short book also sheds light on another, less well-known aspect, which is the history of this industry, which is deeply linked to the colonization of Africa and Asia and the accompanying massive slavery and violence, in addition to the relationship of palm oil to the development of the Industrial Revolution and its role in creating basic commodities through which Europe accumulated, and is still accumulating, huge fortunes. .

The oil palm is one of the most abundant and widely used plant species in the world. The plant Ellis ginensis [the scientific name for this type of palm], from which we get most of the world's consumed palm oil, is native to West Africa, where people have grown and valued them for centuries. From its dazzling saffron-colored seed pods (which when ready to harvest weigh more than 10 kilograms) Africans have for thousands of years extracted not only cooking oils, but also lamp oils, cosmetics, medicines, art materials, ritual oils, and dyes. From its sap comes palm wine and a variety of remedies. From its leaves, houses are roofed and arrows and spears are made. Yesterday and today, the intensely fragrant palm oil was used for ceremonial and spiritual purposes in Africa and its diaspora. Many consider the red virgin palm oil to be the taste of homeland, family and history.

But the palm oil you and I know is something else entirely: Like a multi-faceted goddess, synthetic derivatives of the palm fruit can be found in more than 200 different ingredients in food, industrial, and detergent products around the world. Bleached, deodorized, refined oil has become a staple in the diets of billions of people around the world, especially the poor.This globally traded neutral commodity originates from intensive manufacturing facilities located primarily in Indonesia and Malaysia, but also in West Africa and Latin America, typically built on vacant lotus that was once home to rainforests. Fertilizers, insecticides and herbicides used in the intensive cultivation of this commercial crop often find their way into local waterways. In these factories as in the nearby commercial farms, where lab-grown Ellis ginensis trees grow in neat rows nine meters apart, most workers are somehow displaced, sometimes several generations ago. The cause could be civil war, an imperialist-supported counterinsurgency campaign, the environmental effects of mining, land dispossession, or governmental or international "development" incentives seeking to relocate workers to companies that need cheap labour. As a result, palm oil workers usually rely on precarious labor to provide the necessities of life. Even those who nominally own the land on which they work find themselves implicated in systems of exploitation.

Today, palm oil or its derivatives are found in about 50% of supermarket foods in the world; In processed and processed foods such as baked and packaged goods, noodles, dairy products, and snack foods.

Today, you and I find palm oil or its derivatives in an estimated 50 percent of the world's supermarket foods, mostly in processed and processed foods such as baked and packaged goods, spreads, noodles, dairy products, and snack foods. But palm oil also enters our bodies in small amounts through an astonishing variety of preservatives, thickeners, stabilizing agents, coagulants and additives. Palm oil's unique chemical composition and extreme cheapness make it an ideal additive to processed foods to give them a longer shelf life and facilitate their transportation through world-wide trade networks. Palm oil covers our bodies, too: it makes up the bulk of cosmetics (although some luxury brands sometimes brag about avoiding it). It is an important component in the production of plastics, dyes, ink, coatings, and even paper products, including wrappers. It is also included in many pills, tablets, suppositories, and other medical consumer products. It is also used in a multitude of industrial processes and manufactured products, in particular surfactants that are an important part of machine lubricants, dye and coloring processes and a wide range of other processes. In 2020, 72 million tons of refined palm oil were consumed worldwide, roughly 20 pounds [9 kilograms] per person. Its intensive cultivation has changed our world: more than 27 million hectares of the planet are devoted to the cultivation of oil palms, which is more than New Zealand and nearly the size of all farmland in France. Emptying forests, especially peat lands for oil palm cultivation, adds significant amounts of carbon to our atmosphere, approximately 6% of total global annual emissions, which contributes to raising the serious risks of climate change, and In 2020, 72 million tons of refined palm oil were consumed worldwide, roughly 20 pounds [9 kilograms] per person. Its intensive cultivation has changed our world: more than 27 million hectares of the planet are devoted to the cultivation of oil palms, which is more than New Zealand and nearly the size of all farmland in France. Emptying forests, especially peat lands for oil palm cultivation, adds significant amounts of carbon to our atmosphere, approximately 6% of total global annual emissions, which contributes to raising the serious risks of climate change, and In 2020, 72 million tons of refined palm oil were consumed worldwide, roughly 20 pounds [9 kilograms] per person. Its intensive cultivation has changed our world: more than 27 million hectares of the planet are devoted to the cultivation of oil palms, which is more than New Zealand and nearly the size of all farmland in France. Emptying forests, especially peat lands for oil palm cultivation, adds significant amounts of carbon to our atmosphere, approximately 6% of total global annual emissions, which contributes to raising the serious risks of climate change, andwhich are not necessarily evenly distributed .

How did it all happen? Our story must begin at the roots of this global commodity, which stems from the European colonization of West Africa in the nineteenth century, where the lives of millions of people were sacrificed on the altar of that three-faced God: capitalist accumulation, white supremacy, and imperial rivalry.

In order to tell the story of palm oil as a story of capitalist human sacrifice, we have to start from 1897, when the “British punitive campaign” was launched against the Edo Kingdom, in what is today Nigeria, which was allegedly a campaign to spread civilization, avenge British honor, and intervene to eliminate the An African kingdom whose practice of human sacrifice was presented in the British press in an inflammatory manner. In fact, besides the lust for conquest and the greed of lowly officials, one of the main motives of the campaign was to secure the lucrative production of palm oil in West Africa for British companies.

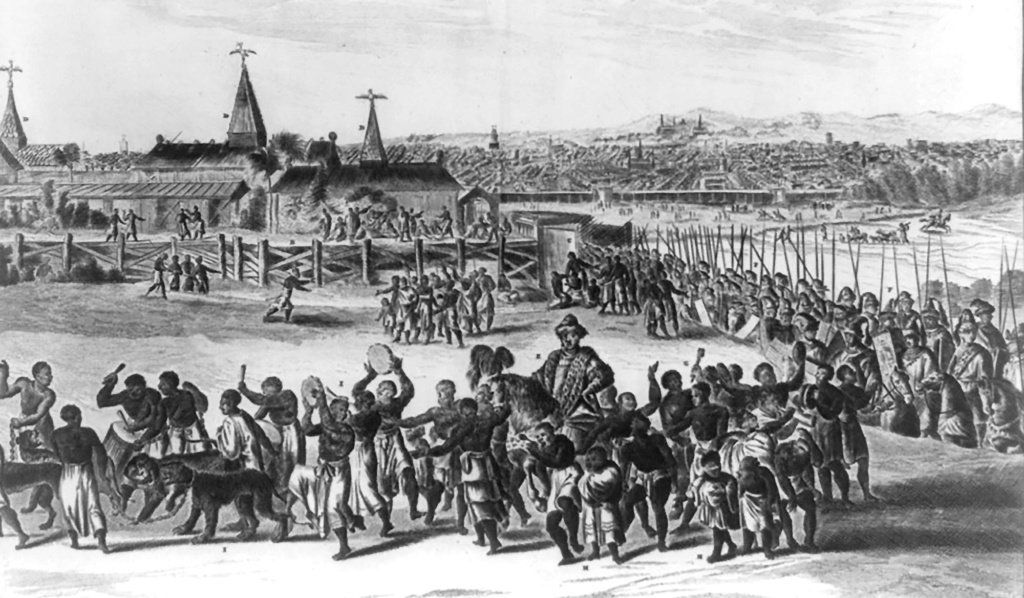

Benin City as drawn by the Dutchman Olfert Dabur in 1668.

Human sacrifices on the altar of capitalism

Europeans have known the Edo Kingdom [also known as the Kingdom of Benin after its capital] since the fourteenth century as an organized and powerful political community in West Africa, organized by a political spiritual leadership represented by the Oba and his royal family, of which the influential widowed queen was the most prominent member. Its capital, Benin, was of legendary grandeur and engineering sophistication, and rivaled major European cities in size and social organization in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In this strictly social stratified society, the antiquities known today as the "Benin Bronzes" embodied centuries of Edo history, and their cultural significance has no European equivalent. Today we have a few pictures of these ruins in their original location, in which we see statues varnished with palm oil on the altars, glazed hanging dishes adorning the broad pillars on which the vast ceilings of public buildings were raised, and sculptures inspired by nature adorning the exterior architecture. Some of these relics were decorative, embodying the fruit of generations of high craftsmanship and a specialized division of labour, while many pieces were records of aristocratic lineage or of historical events in the kingdom, i.e. more like a carved library. Others were made for trade, including with Europeans; trade a lotWhat was denominated with palm oil .

Palm oil enters our bodies in small quantities through an astonishing variety of preservatives, thickeners, stabilizing agents, coagulants and additives.

In some of its scenes, these bronzes embodied the artistic depiction of an African empire built on the riches of palm oil. The capital of this empire was the economic, administrative, cultural and religious center of a sprawling system that subsisted on this versatile material. The conditions and relations of palm oil production often depended on one's standing in the empire: families of rich notables could supervise large groups of slave laborers who tended the plants, climbed them to harvest their fruit, supervised the fermentation process, separated and purified the oil, and transported the commodity to market. The captive groups of the Ido also paid their ransom with palm oil. Workers and others outside the elites would produce their own oil to be used or sold for subsistence or taxation. As in many diverse societies in the region, palm oil played a pivotal role, and its production relationships shaped an entire lifestyle.

Today, thanks to the efforts of the Nigerian government and its allies over decades, there is a strong movement to compel western museums and cultural institutions to return these antiquities. The British seized the bronzes when they burned the capital, Benin, to be auctioned in Europe later that year, to offset the costs of the campaign itself. Since 1991, the bronzes have been held in the Sainsbury wing of the British Museum . The pavilion is named after the wealthy Sainsbury family, many of whose members have sat in the British House of Lords. The family amassed the wealth that enabled them to present this gift to the British Museum through its successful supermarket chain, which includes palm oil in half of the products on its shelves.

Right (top) Britons collecting antiquities from the Royal Palace of Benin after it was looted, 1897.

Left (bottom) Benin bronzes in the British Museum, The New York Times.

The British punitive campaign against the Edo kingdom, as its brazen name indicates, was a mission to elicit imperialist racist revenge. In the 1840s, Britain was seeking to consolidate its control over the areas known today as Nigeria and make it its exclusive sphere of influence. That was settled for her at the infamous Berlin Conference of 1885, when European colonial powers shared Africa in the middle of an ornate room, on a cold, rainy winter's day in the capital of the newly unified German Empire. The conference was preceded by decades of competition among European powers to secure exclusive (extremely unfair) agreements with African kings and trading cartels. In the aftermath of the Berlin Conference, the British Empire repeatedly launched "punitive campaigns" to punish the African kingdoms and cartels for their refusal to comply with these extortionate agreements, for stopping the export of palm oil, or for their almost any opposition to the accumulation of British capital.

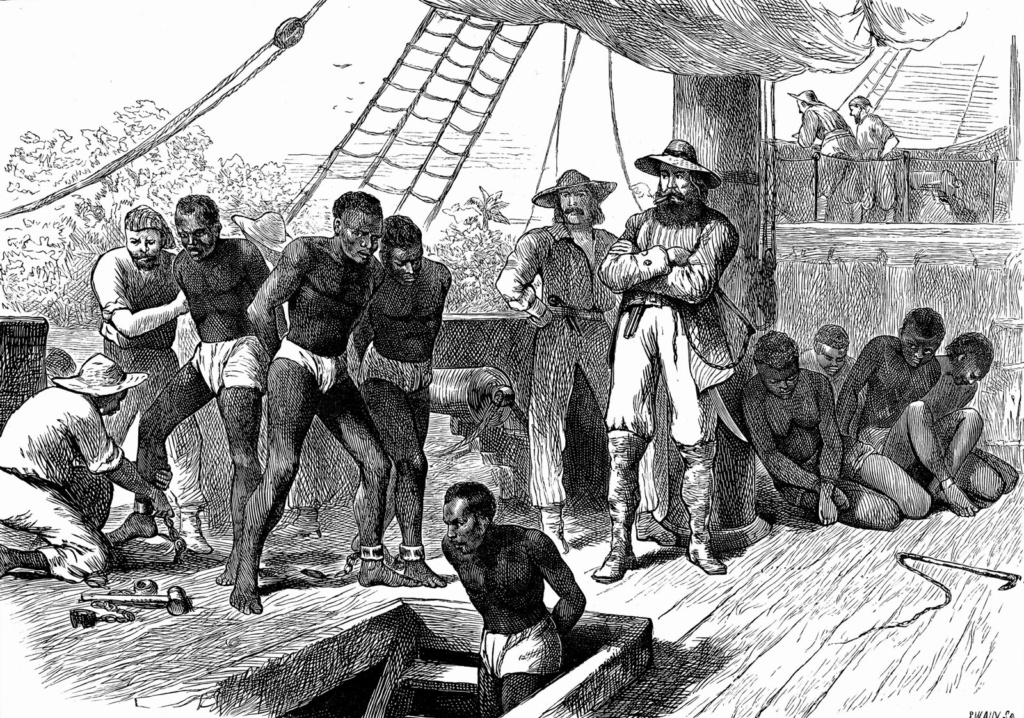

The campaign was an example of the type of imperialist actions that ended an earthquake century in the region. The abolition of slavery in the British Empire began with the imposition of restrictions on the slave trade in 1807, thanks to revolutions that spread across the world, primarily and most importantly fueled by the slaves themselves, but also with the participation of the working classes, abolitionists, and religious reformers in England. In the wake of this popular victory, many of the Liverpool merchants, who had accumulated fortunes through these horrific atrocities, directed their projects towards extracting palm oil from West Africa - including the area the British knew as the Rivers of Oil, after palm oil - and exporting it to Europe. The West African ocean-going oil market arose out of the heart of the slave trade, where it was usually loaded onto ships to feed enslaved Africans during the voyage, or to lubricate their bodies on arrival, to make them more marketable, or to hide their wounds and scars from potential buyers.

African captives being taken to a ship on the shores of West Africa to be sold as slaves, 1880.

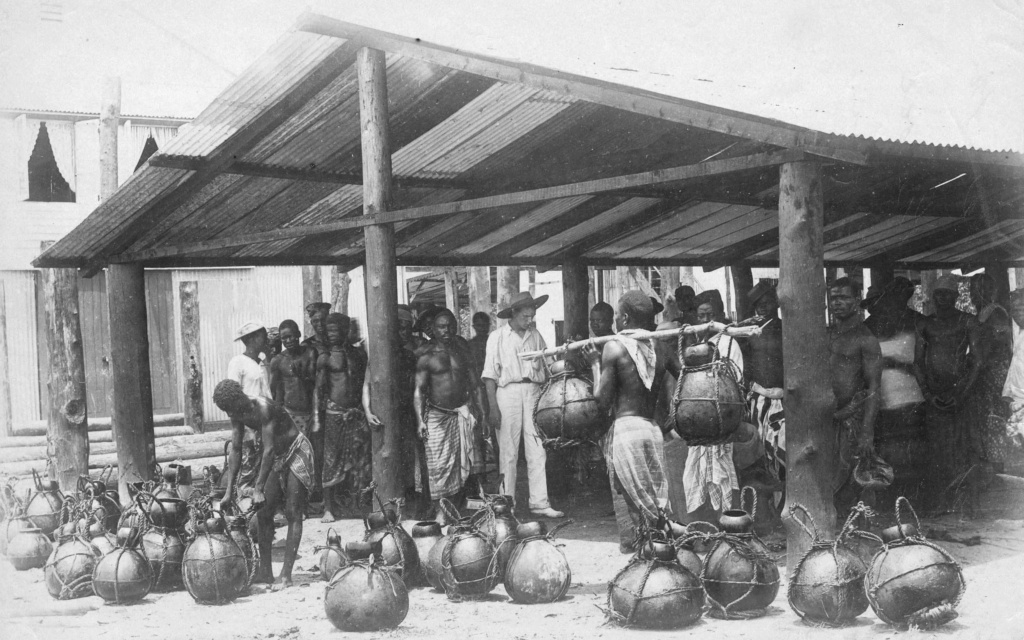

Meanwhile, palm oil has become one of the essential ingredients of imperialist capitalist modernity. To get a picture of the scale of this trade, palm oil imports into Britain (which at the time controlled nearly three-quarters of its global trade) increased 566-fold between 1807 and 1897, when its import peaked. That year, 63,147 tons of refined oil were discharged into the ports of Liverpool, London and Bristol, the sum of 8 to 27 million working days of African labor, from planting, harvesting, processing, transporting and selling. Statistics from 1830 indicate that palm oil was sold in Liverpool for ten times the price at which it was bought from African producers. In Europe, palm oil was a necessary grease for industrial machinery, railway locomotives, steam engines, and more. The oil was also essential in a number of new consumer products in the late 19th century: soap, cheap candles, tin cans, and later,Margarine . It was a craving for this seemingly magical substance that brought Europeans to West Africa. The popularity of the ornamental use of palm trees in Victorian London testified to the importance of this crop, both as a raw material and as a souvenir of his imperial sheep.

Intensive oil palm cultivation has changed our world. More than 27 million hectares of the planet's area is devoted to oil palm cultivation, which is more than New Zealand and nearly the size of all farmland in France.

In the early nineteenth century, British merchants contented themselves with purchasing African palm oil on board ships or from stores moored at the mouths of rivers, leaving the extraction of the oil from the interior to coastal African elites. European merchants made huge fortunes by purchasing goods from African merchants on credit or "trust", to ensure a regular flow of goods. By the middle of the century, the share of old British family businesses in coastal warehouses had fallen in favor of the "palm oil barbarians", the ruthless European entrepreneurs, who were reviled in Britain for their crude behavior but prized for their profit to British investors. As European demand increased, steam ships, antimalarial drugs, and other technologies appeared, and joint-capital companies began to control trade, Europeans began to move little by little to inland lands and directly control palm oil production. As Walter Rodney asserts, through the palm oil industry, “Liverpool companies are no longer exploiting Africa by physically transferring their labor to another part of the world, but are now exploiting their labor and raw materials within Africa itself.” Ship holds and accounting books that used to turn Africans' lives into a perishable and replaceable raw labor force to be sold in the settler colonial countries of the Americas, are now bringing the fruits of African labor to Europe.

But by the turn of the century, the demands of industry and rising imperial rivalry had encouraged the British administration to take harsher steps. The European empires, which hid behind the language of bringing civilization to ignorant peoples, saw Africans as wasting precious resources because of their insistence on traditional methods of agriculture and trade, which must be organized in more rational and scientific forms, they claimed, for the benefit of Africans themselves.

A Dutch map of West Africa dating from 1664 showing the Edo Kingdom with its capital, Benin, indicated by an asterisk.

It is important here to point out the centrality of the company as a capital structure in this story; This strange legal invention turned out to be true. We must remember that this perverted, savage entity, born to facilitate the colonial and enslaving projects of the European bourgeoisie, and whose purpose is to generate profits for the shareholders, was granted legal status in European law long before this law recognized most of the inhabitants of the earth as fully human. long. By the time of the punitive campaign, palm oil trade was dominated by the interests of big corporations, and these corporations were able not only to generate significant capital and retain skilled merchants and managers, but also to employ special military forces and powerful lobbyists.

Meanwhile, the punitive campaign of 1897 for the public in Britain was justified by the idea of the civilizational influence inherent in free trade, and as a way to end the barbaric practice of human sacrifice. For decades, the Ido kingdom has been portrayed in the British press as a bloody city ruled by a ruthless tyrant who orders the sacrifice of live, lubricated meat to appease his brutal gods. But perhaps what the British horrified more than human sacrifices was the way in which the oba invoked the supernatural power of "juju" as a reason to prohibit or monopolize the exchange of certain goods, threatening the idea of "free trade" that so fascinated Europeans. Palm oil was considered a sacred substance and was therefore made available to the Oba, who strictly regulated its trade, thus upsetting British merchants.

The question of how, why, and with what repercussions the Edo kingdom practiced human sacrifice remains a matter of historical debate, overshadowed by the fact that the only "reliable" records we have are those brought by Europeans, usually for the purpose of defamation and legitimizing missionary or military intervention. While few historians doubt that these practices did take place, some argue that they were less bloody rituals than a death sentence, within a religious community in which state actions are endowed with spiritual value. We may never be sure of the role human sacrifices played in the Edo kingdom, and that is not very important to our story. What matters most is how the British used the story of human sacrifices. They justified their invasion in the name of intervening to stop this heinous practice, while the sacrificial stories that were presented in a showy manner contributed to obscuring, normalizing and belittling the violence of the invasion itself, which applies to the imperialist system of which this violence was a part.

Africans sell palm fruits to a European buyer, in the rivers of oil in what is today Nigeria, at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Africans resisted all this in the ruins of the Ido kingdom and elsewhere. Displaced Oba nobles and soldiers waged a guerrilla war against the British occupation for nearly two years after the fall of the kingdom. The Oba, despite his humiliating denials, never formally surrendered his throne, and today his descendants still hold a symbolic position in Nigeria's Edo Province. Even when military and political resistance was impossible, Africans found many ways to resist and rebel. This included refusal to work, infrastructure sabotage, food spoilage, resource diversion, and smaller work. In 1929, the "Women's War", with more than ten thousand heroines, broke out as a result of the mechanism in which the British colonial administration ruled the country through high-ranking agents, usually corrupt men, who collected heavy imperial taxes, especially from palm oil merchants.

In the story of palm oil extraction, capitalist processes intersect with local hierarchies and grievances, including the persistence of slavery and the domination of old and emerging elites. But these complexities should not discourage us from realizing that capitalism, racism, and colonialism have all overlapped and shaped each other in this context, which is still continuing in our time. In her fascinating study of Indonesia's forests, much of which is being mowed today to make way for large palm oil plantations, anthropologist Anna Tsing urges us to understand the evolution of capitalism by looking at the clashes between the logic of global accumulation that capitalism carries, cultures, lifestyles, and local power structures. By tracing palm oil, we can illuminate the interactions of power and resistance that are the raw material of the world we create together, and understand how the past and the present are intertwined.

Fitch Europe and its industry

The main reason for the British and other Europeans' interest in palm oil production in West Africa was that they needed it as an industrial lubricant. The accelerated industrialization in Europe in the nineteenth century required millions of liters of refined palm oil annually, either alone or added to other oils, as a means of cooling and protecting industrial machinery in factories, public workshops, railways, and more. It is no exaggeration to say that refined African palm oil has greased the wheels of imperialism, both literally and figuratively.

This was the primary market to which Liverpool merchants turned after 1807, when they were forbidden from the very profitable slave trade. These traders hired chemists and investors to develop new formulations and uses for palm oil and to promote its use among industrialists and others. Before the spread of palm oil, tallow was usually used by Europeans, but by the nineteenth century, with the increasing demand for it by European imperial armies and the disruption of supply chains by war, its costs had risen. In addition to being relatively expensive, tallow was foul-smelling and could spoil, especially during long sea voyages and in hot, humid bushes. On the other hand, while the costs of importing palm oil were initially high, the expansion of its economy and the emergence of steamships soon pushed prices down. By the punitive expedition of 1897, its price had fallen sharply, in part because much of West Africa was dedicated to its manufacture, as well as competition between European merchants. In addition, the technology of extracting refined oils from coal and oil was becoming increasingly popular at that time due to its price and the precision with which it could be engineered for specific industrial purposes.

Thus, one might think that the British Empire would find palm oil too cheap to justify the military force invested in the punitive campaign, and later in the colonial administration. In fact, this created a state of reluctance in the colonial government, which did not want to be burdened with a new, unprofitable rebel "protectorate". But as Karl Marx pointed out and Rosa Luxemburg emphasized, contrary to the rosy predictions made by bourgeois political economists, the reaction of capital to lower prices and market saturation is simply more violence, in order to create new horizons of accumulation. Across imperialism, empires compete to open new markets or wage wars to exterminate peoples or destroy their accumulated wealth. In the case of the West African palm oil region, this reaction was that European companies expanded their business from shore to inland in an attempt to cut back African middlemen and undermine the power of local elites who controlled the commodity's supply.

Between the beginning and end of the nineteenth century, palm oil imports to Britain multiplied 566 times, constituting one of the main components of imperialist capitalist modernity.

In the late nineteenth century, palm oil was the most popular fuel for candle production, before the rise of coal and petroleum oils and the widespread spread of electricity. In contrast to tallow, palm oil candles burned cleaner and less smelly, and they were cheaper to produce because the bulk of the labor employed to extract the oil was remote African exploited labor. But palm oil candles were presented to European consumers as a moral choice. Liverpool palm oil traders and their customers, especially candle and soap makers, marketed their products as a gift to Africans that could encourage them to work in palm oil exports as a way to move from the institutions of slavery to a new stage.

In the 1830s, chemists developed techniques that led to bleaching palm oil and removing its odor to be used as a basis for soap making. British soap consumption doubled between 1801 and 1833. While palm oil began as an additive to luxury soaps, the Industrial Revolution turned it into the basis of a commodity that became a daily need. It celebrates companies like Lever - the predecessor of today's Unilever, which remains one of the world's largest consumers of palm oil - as a visionary benevolent capitalist, for its owner William Lever's "enlightened" policies toward his European workers. But the company's treatment of African workers stemmed directly from the brutal mechanisms of oppression inflicted on them along the coasts themselves during the slave trade, developed and incorporated into the latest theories and practices of commercial plantation management.

Right (above) women workers at the Lever Company's Sunlight Soap Factory in Liverpool, 1897.

Left (bottom) drums of palm oil arriving at the Port of Liverpool for use in the soap making of the Lever Company, 1897.

The plantation model, says palm oil historian Jonathan E. Robbins, is a profound process that works to “create a new nature and delocalize a particular place by emptying it of vegetation, expelling its inhabitants of humans and animals, and fencing, draining and irrigating the area until it conforms to a specific global model.” All this occurs within a broader economic framework that provides resources markets for inputs and markets for outputs. This farm is a technology that would not have existed except with modernity and colonialism; A machine that turns intertwined land and labor into private wealth.

Lever farms in West Africa were not as successful as they had hoped, in part thanks to the daily forms of resistance and rejection by the workers. In the Congo during Belgian colonialism and elsewhere where Lever held concessions, workers frequently ignored or intentionally misunderstood instructions, found ways to divert resources, or refused to work or work hard, leading the company to “invent” even bloodier and exploitative conditions for workers. Including two issues that are still critical today: unfair debt restrictions and contracts, and the use of militia and gang violence, overt or covert.

The success of Lever, who entered the industry relatively late, stemmed not so much from the quality of his product or the efficiency of his operations as from his marketing acumen. By the 1920s, palm oil importers, including Antonius Jurgens and William Lever [whose companies would merge to form Unilever years later], were determined to expand their market and wealthy enough to buy the luxury retailers, the predecessor of today's supermarket, to provide direct access to Consumers across chains of stores. By the end of the last century, British people were consuming an average of 17 pounds [1.7 kilograms] of soap per year. This was done by associating soap with the dominant values of the era; Soap was marketed first to middle-class women and then to middle-class women, as a way to take care of the family and the home and protect them from the dangers and filth of the outside world. These advertisements exploited and reproduced images of gender and family that ultimately served capitalist accumulation, as the radical thinker Silvia Federici explains. Such advertisements normalized the image of the proletarian woman: an unpaid domestic worker who would be expected to provide the reproductive work that would enable the breadwinner to return to work every day, and to bear and raise a new generation of workers as well.

The accelerated industrialization of 19th century Europe required millions of liters of refined palm oil annually, as a means of cooling and protecting industrial machinery in factories, public workshops and railways.

As with candles, palm oil soaps were marketed using the language of white supremacy. In some advertisements, black children were turned white when using soap, associating dark skin with animal filth and decadence, and whiteness with purity, cleanliness, and civility. Later, advertisements came to express explicitly that the transmission of "modern" soap and hygiene to the "lower races" of the land was part of the task of the empire and the burden of the white man. The racist imperialist project that greatly benefited the ruling class to the middle and then working classes was presented as an inter-ethnic project, seeking to alleviate the rising class tension.

In this sense, soap was a truly fetishistic commodity. For Karl Marx, who must have seen these ads almost daily near his home in London's Soho, commodity fetishism is essentially the process of forgetting; It expresses how certain commodities are magical or inherently powerful, and seem to us to have come out of nowhere, separated from the socio-economic mechanisms that produced them. What is forgotten here are the roots of soap stemming from the imperialist exploitation of African labor, and the factory workers who turned palm oil into soap.

This kind of segregation persists in our world today. It is not only that we “forget” that many of our daily commodities, including soap, are based on palm oil, nor that many of us are ignorant of the enormous human and environmental costs of producing it. Rather, this fetish extends to the world of advocacy, activists and NGOs that are active in the field of palm oil. For understandable practical reasons, many campaigns take on attractive fetish targets, such as the tragedy of the charismatic orangutan , whose natural habitat is being deprived of deforestation. Other times, campaigns target specific products, such as the famous Nutella. Small-scale palm oil producers or disenfranchised indigenous smallholders are often highlighted as the perfect victims of Western consumer indifference or corporate bully.

It's kind of understandable, these organizations compete for people's attention and sympathy, trying to mobilize and influence a huge and powerful industry. But it ultimately contributes to creating a fetish reminiscent of the fetishism that appeared in soap ads in the 19th century, and not just when it depicted brown people needing the favor of a white consumer. By focusing on this animal, human or victim of the palm oil industry, this company or that product, these campaigns unintentionally contribute to forgetting the overall picture that connects all aspects of this commodity, which starts from the early history of palm cultivation in West Africa.

https://www.7iber.com/politics-economics/%D9%81%D8%B5%D9%88%D9%84-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%AE-%D8%B2%D9%8A%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%AE%D9%8A%D9%84/?fbclid=IwAR05S1nHvpk_F8R9JgepGTAUA_wmMlHP6iuNkhrxcEOFq-VjAMzfEdj-QtY