Learn about the history of cigarettes and government intervention in the spread of smoking

On July 11, thousands of people heard a remarkable story on NPR and WBUR's Here and Now, in which two respected historians asserted that Americans would not have been as dependent on tobacco as they are today without the massive support of the US government. The claim was surprising to many, as Big Tobacco is often seen as at odds with the government, due to the latter's heavy-handed disclosure requirements and public aversion to disease and death of its citizens. There was only one problem. Both historians did not mention the source of the story, which belongs to another historian named (Sarah Milov), as they stole the story from her new book, “Cigarettes: A Political History.”

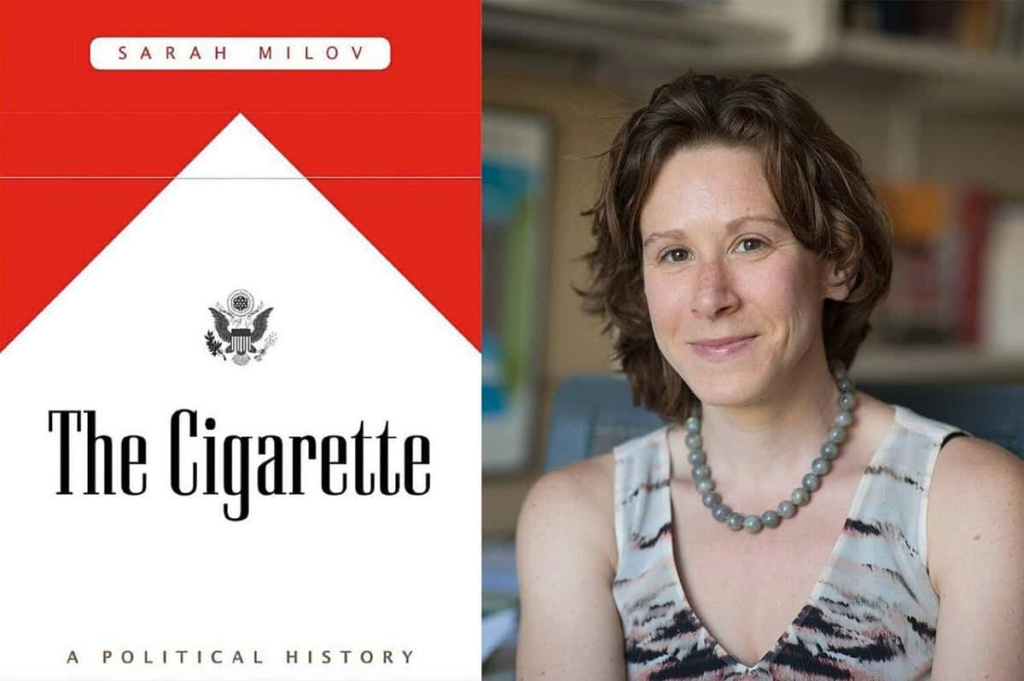

Cigarettes: A Political History, by Sarah Milov.

The story spread within days, and it was first published in The Lily under the headline: "They have credit, and she misses it." “Every word they said was from my book,” Miloff, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia, told The Lily, noting that her claim would be completed within that year. Twitter and other media outlets exploded with countless posts and stories on the subject. The historians (Edward Ayers and Nathan Connolly) quickly apologized, and so did the radio stations.For many, the event epitomized a rumor dynamic at the academy, where male researchers have long won praise for the work of their female colleagues.

The Cigarette Book, written by Sarah Milov

Although the controversy generated "great publicity" for Milov's book, Jezebel noted, the incident itself began to garner more attention than the book itself. It would be a disgrace, since the public will miss the critical information in the book and its accurate and devastating indictment of government complicity in the worst excesses of American capitalism. The Cigarette looks beyond individual consumers and their choices and directs its insight directly into the larger phenomena that shape our lives: the demands of war, including the rise of organized interest groups, the collapse of government regulators, and the massive and hidden impact of megaprojects.

Cigarettes at the turn of the 20th century were still somewhat of a fringe product, with moralists deriding smokers as “slaves to the little white cigarette,” fanatics deriding smoking as an immigrant habit, and many shunning them in favor of pipes, cigars, or chewing tobacco. It took federal government intervention to turn cigarettes into a popular consumer good. In 1917, Congress appropriated money to put cigarettes in the rations of soldiers preparing to fight in World War I, hoping to distract them from "more dangerous vices."

The cigarettes were lit, and the tobacco companies embarked on innovative advertising campaigns to ensure that the “valoring of cigarettes in war” could continue in peace. From 1914 to 1920, American tobacco consumption in cigarettes jumped from 7 percent to 20 percent. Federal intervention was to continue into the next century to determine whether the cigarette was very good or very bad.

A stereotyped image of a smoking woman from the 1920's

As demand increased, more problems arose, as the price of tobacco leaf fell. The farmers who were growing the tobacco used to make cigarettes felt "weak and angry". Their labor made a handful of powerful white men exceptionally rich, but the farmers (not to mention the pickers, who worked in barbaric conditions, those who rolled cigarettes and made their profession obsolete by the meddling of machines) felt exploited and devalued by The “oligopoly” of the American tobacco companies (R.J. Reynolds, Leggett, Myers, Lorillard and James B. Duke).

Drawing on the legacy of folk ancestors, farmers tried to organize cooperatives so that they could charge tobacco prices to companies. But the corporations and their allies have crushed the cooperatives, through intimidation, litigation and even outright sabotage. In the end, salvation came from the economists Franklin D. Roosevelt, who quickly diagnosed tobacco's economic problem: overproduction. Tobacco chokes off trade.

Federal officials sought as part of the New Deal to control the economy and eliminate unnecessary competition. To eliminate tobacco overproduction, the Federalists created a program whereby they would pay farmers to stop growing the plant, to take fertile farmland out of production so that the prices paid for tobacco would remain high, and uncooperative farmers were heavily taxed.

World War II was another fortunate opportunity for the industry, as cigarette companies ingeniously capitalized on the wartime enthusiasm and price hikes that farmers received annually from 1940 to 1946. After the war, the companies devoted themselves to expanding the cigarette market across the country and around the world. . They have invested more in promotional advertising than ever before.

“Cigarettes were once a vice of immigrants and juvenile delinquents,” Miloff writes. But war, advertising, and Hollywood helped broaden, professionalize, and glamourize smoking's appeal. By 1955, nearly a quarter of American women and more than half of American men were active smokers.

As a result of strong corporate pressure, the money donated to Europe in the Marshall Plan was used in the tobacco industry; One billion dollars has been allocated to him alone, “a figure that represents a third of the total food aid.” In theory, this was intended to support European industrial economies. In effect, he intended that European cigarette companies would use American tobacco leaves to make their products and get European consumers addicted to smoke-dried American tobacco. Tobacco companies also consolidated their expansion into foreign markets through lobbying at international and trade fairs.

By 1949, according to one survey, between 85 and 90 percent of West Germans preferred the taste of smoke-dried American tobacco to the ancient Greek or Turkish varieties long smoked by older generations. Thus, by the middle of the 20th century, the American cigarette had taken over the world.

Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images

The farmers were pleased with the arrangement, as were the tobacco companies. However, troubles are brewing in the motherland. During the 1950s, newspapers began to run more and more stories about the disturbing relationship between smoking and lung cancer (which was noted as early as 1939). For several years the tobacco companies were able to quell health concerns through artful media and public relations, and smoking rates continued to rise. But the federal government stepped in again when, in 1964, Surgeon General Luther Terry issued a report declaring in no uncertain terms the link between cigarettes and cancer. Hence began what will end with a radical reassessment of the relationship between the government and tobacco growers, if not the tobacco companies themselves.

The Federal Trade Commission immediately began drafting regulations that would severely restrict cigarette companies' advertising, for example by requiring a health warning to be included in all radio and television advertisements. But before these regulations were imposed, the cigarette companies went on the defensive, led by Fred Royster, a well-connected warehouse owner and farmer known in North Carolina as "Mr. Tobacco," backed by industry trade groups such as the funded Tobacco Institute. Well funded. Corporate allies persuaded Congress to repeal ad warnings and reduce the warning label's appearance on cigarette packages. Instead of asking, "Cigarette smoking is dangerous to your health," they suggested weaker wording, "Cigarette smoking may be dangerous to your health." The companies, with the help of D.C.'s top lawyer and soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas, engineered a sweet deal with the Department of Justice whereby they were able to regulate their own advertising.

With traditional mechanisms of federal regulation effectively neutralized, public interest lawyers have moved to more creative approaches to confronting these corporations. Led by unorthodox 27-year-old lawman John Banzhaf, these attorneys convinced the federal government that it should have put in prime-time ads showing not only the "pleasures of a smoker's life" but also the "horrors of a smoker's death." An example of such ads is that of (Bill Tallman), the actor who plays the Attorney General who loses his case every week to (Perry Mason), speaking about his lung cancer: “Take some advice about smoking and losing from someone who battled it for years.” He passed away at the time the ad was aired.

Banzhaf had meanwhile become a law professor at George Washington University and founded Action on Smoking and Health from his college office. He began mobilizing his students to sue the agencies, and successfully argued for non-smoking sections on planes. His slogan was "Suing bastards."

Beginning in the 1970s, the philosophy of deregulation took hold. Liberals worried about agency takeovers joined with conservatives suspicious of big government stifling big business, and together they persuaded the government to weaken provisions requiring non-smoking sections. As the agencies continued to weaken during the 1970s, another strategy for change had to emerge. Indeed, the "Non-Smokers' Rights Movement" appeared.

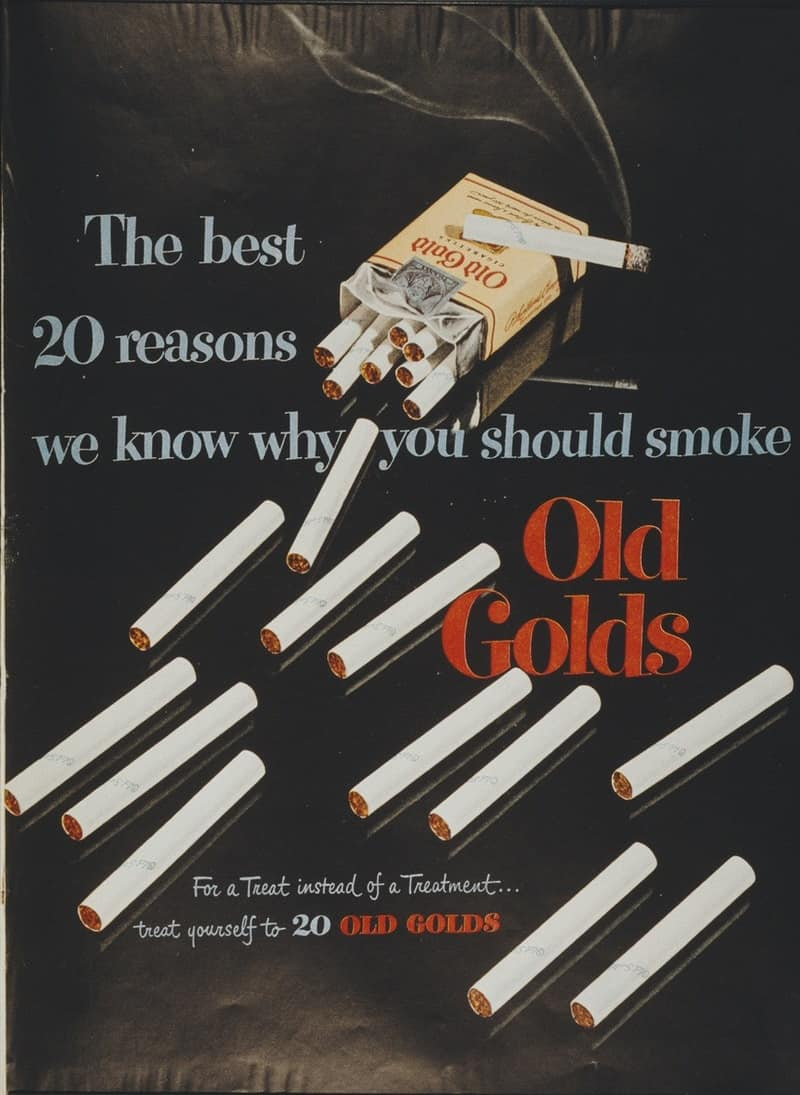

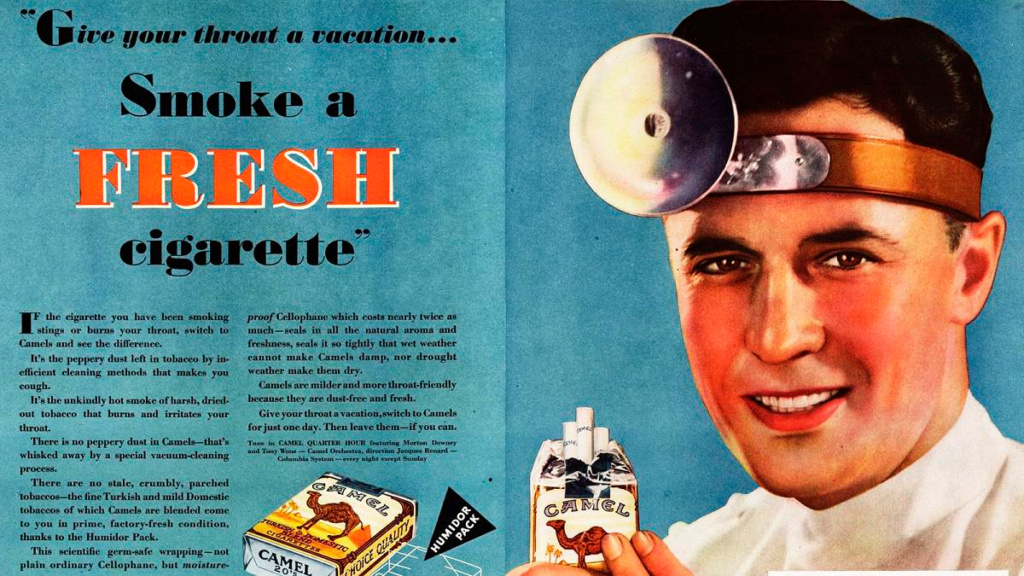

A promotional poster called the medical benefits of smoking

In 1971, Clara Gwen, a Maryland housewife whose youngest daughter was allergic to smoke, founded GASP to combat tobacco pollution. GASP quickly spread across college towns and liberal enclaves, with the goal of making what they called the "silent majority" as visible as possible. Members raised awareness of their cause from Berkeley to Flint and loftily demanded non-smoking spaces in their workplaces and resting areas. Other activists sued their workplaces, arguing that they had the “right” to quit smoking as some were affiliated with the GASP group, some with Banzaf's ASH group, and others working alone.

The "non-smokers' rights" movement arose a decade before evidence of cancer linked to secondhand smoke was discovered. “The calls for non-smoker rights were motivated patriotic, not scientifically,” Miloff writes. It was based on the non-smokers’ emphasis on virtuous citizenship, and was fueled by resentment of smokers.” Non-smokers resented the entitlement of their fellow smokers, and their refusal to consider the feelings of those nearby whenever they lit their cigarettes. And though Milov is often a bit harsh on GASP, criticizing its adoption of "liberalization" rhetoric even when hiding within the "safe confines of liberal suburbs," she accurately charts how its members and other activists have made significant gains against the cigarette companies.

As their lawsuits met with mixed success, middle-class activists began appealing to corporations directly, arguing that restricting smoking could be beneficial in the bottom line—reducing sick days, disability costs, housekeeping burdens (because smoking damaged equipment and furnishings), and legal fees ( Because smokers were twice as likely to have accidents as non-smokers. A generation of neoliberal economists and many insurance companies agreed with them. (As a result, insurance companies have begun to selectively sell insurance policies at discounted rates to non-smokers.) “The tobacco smoke in the air is a silent drain on a company's resources,” notes Milove, “perhaps a metaphor for the hidden costs of the smokers themselves.” Companies saw no-smoking policies become increasingly common during the 1980s.

This happened because of the fierce opposition of the workers' organisations. Where unions had fought so hard back in the 1940s to win smoking breaks, when it had to be done, they wanted it to be on their terms, through collective bargaining. However, by the 1980s organized labor had lost much of its power because of these breaks, not to mention the tactics of non-smoking activists. Eventually, smoking periods—unproductive times during which workers can take a break and smoke—are discontinued, and more work takes their place.

“Drawing on cost-based analyzes of private behavior and exposing collective programs that have existed for decades,” Miloff writes, “the non-smokers’ rights movement has reshaped what Americans believe government owes to citizens, and what citizens owe government. And in their remarkable successes, they have inadvertently catalyzed a conservative political strategy whose far-reaching implications are incomprehensible, and very real.”

Tobacco farmers suffered greatly. By the 1980s, Republicans had become increasingly suspicious of the federal tobacco program and of massive government intervention in the free market. Democrats became increasingly suspicious of Big Tobacco, especially its biggest champ in Congress (Jesse Helms). Even Big Tobacco was strained by the federal program, because it was buying more tobacco leaves from growers abroad since it was much cheaper for them to grow them.

By the end of the 20th century, 90 percent of smoke-treated and (Burley) tobacco was grown outside the United States. After being repeatedly weakened over the years, the federal tobacco program finally ended in 2004. Since then, tobacco is grown on annual contracts between companies where they can effectively dictate the prices they want, and individual growers lack the right to any real collective bargaining.

Today's smokers are poorer than non-smokers and their level of education is lower. And their cancer rates are higher. They are always told that it is all their fault.

When consideration finally came to Big Tobacco, the government's influence on it turned out to be insufficient. State governments have battled for years with the largest cigarette companies, demanding that they pay for the massive health care costs associated with tobacco. In the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, the companies agreed to pay state governments more than $200 billion for 25 years (a paltry sum compared to the costs of tobacco-related illnesses), but in exchange they got something bigger they've always wanted: "an end to class action and an end to judgments." punitive measures in individual cases.

State governments that relied on these funds to balance budgets did not want litigation for fear of jeopardizing the companies' ability to continue writing checks. For health advocates, it was "a complete public health failure and a corporate coup."

Today only 15 percent of Americans smoke, while in the middle of the century it was about 50 percent. It is estimated that anti-smoking activists have saved 8 million American lives over 50 years. Today's smokers are poorer than non-smokers and their level of education is lower. And their cancer rates are higher. They are always told that it is all their fault. “Responsibility for the production and consumption of tobacco, from the seed to the smoke, has been privatized and individualized.”

Tobacco companies don't care how few Americans smoke. The habit of smoking has spread abroad, and cigarette companies now derive most of their profits from international sales. Today, about 80 percent of smokers live in low- or middle-income countries. The tax of internationalizing the cigarette is beyond imagination. As medical historian Alan Brandt wrote, by the end of the century “the number of deaths is expected to be one billion.”

Although The Cigarette is an excellent book, it is not the first book to document the damage done by Big Tobacco. For example, Alan Brandt, in his excellent book The Cigarette Century, recounted the remarkable hypocrisy of the cigarette companies; And (Richard Kluger) in his movie Ashes to Ashes drew the tobacco wars in a fictional style. However, none of these researchers wrote an actual history of people's suffering with cigarettes, including those that revealed the human cost of this industry to farmers, smokers and non-smokers. But Miloff provides the first description of the government's involvement in this extreme human cost, and the way in which big tobacco has evolved, adapted to lawmakers and regulators, and thrived. And the billion people who needlessly lost their lives.

The lessons from her book remain surprisingly relevant today. We are in the midst of revelations that the sugar industry also relied on advertising to distract consumers from the intense addiction. And in the NFL's battles with former football players who died of CTE, the league hired the same lawyers, consultants and lobbyists that Big Tobacco used.

Cell phone companies have also worked tirelessly to hide evidence of the connection between cellular radiation and all sorts of negative health effects. Even with mass shootings occurring daily, the gun industry has pressed to extricate itself from any meaningful oversight. Even more damaging, fossil fuel companies have relied on shoddy science, relentless public relations, and willful spreading of skepticism to cover up the relationship between oil and gas and climate change, a business decision that has increased profits in the short term but may have killed our business. wiped out an entire civilization.

Will we learn from the history mentioned in The Cigarette? Milov's book also eerily shows how the great powers quietly and insidiously shape much of everyday life: privatization, cool advertising, the rise of late capitalism. When we think about how to achieve justice for the biggest crimes, we must turn our attention away from individual consumers and their choices and focus squarely on those who have used their enormous power to engineer entire economies for their own benefit.

Source: websites