The Amazighs of Tunisia... cling to their identity and demand rehabilitation

The Tunisian revolution gave space to many young people to express their opinions, ideas, and demands, regardless of their differences, and Ahmed Mahrouq (Hamada) is one of these young people, but he focuses his interests on demanding the cultural rights of the Amazighs.

Ahmed hails from the Amazigh village of Zaraoua, in the southern governorate of Gabes, a village that has preserved its Amazigh character. Through his professional rapping and singing in the Amazigh language, he seeks to revive the identity of his region and preserve it from extinction.

After the Tunisian revolution, "Hamada" took advantage of the climate of freedom in the country to make his voice heard. In 2012, he and his brother Abdel Haq founded the "Azrou H2Z" group, after his village "Zarawa". Their first song was titled "We Are the Amazighs" and its aim was to revive Tunisia's Amazigh identity.

"Nous ne sommes pas une minorité"

En tant que jeune amazigh parlant la langue Tamazight, Ahmed aspire à éduquer le peuple tunisien sur la vérité de ses origines amazighs et à enseigner aux futures générations tunisiennes l'histoire de « leurs ancêtres amazighs qui ont préservé leur terre et résisté à toutes les invasions ». existence.

Et si Hamada refuse de contraindre un parti à changer ses idées ou ses convictions, cependant, le professeur d'université et spécialiste de l'histoire de Tamzgha (le pays des amazighs), Muhammad Saad al-Shaibani, déclare : « Nous voulons que tout le monde en Tunisie, y compris ceux qui sont arabisés et porteurs de l'identité arabo-islamique, de revenir à la culture amazighe en enseignant la langue Tamazight dans ses lettres d'origine et en la pratiquant.

"We are not a minority"

As a young amazigh who speaks the Tamazight language, Ahmed aspires to educate the Tunisian people about the truth of their amazigh origins and to teach future Tunisian generations the history of "their amazigh ancestors who preserved their land and resisted all invasions". their affiliation and existence.

And if Hamada refuses to force any party to change his ideas or convictions, however, the university professor and specialist in the history of Tamzgha (the land of the amazighs), Muhammad Saad al-Shaibani, says: “We want everyone in Tunisia, including those who are Arabized and carry the Arab-Islamic identity, to return to the amazigh culture. by teaching the Tamazight language in its original letters and practicing it.

He added: "The state must take care of the Amazigh heritage with all its components of customs and traditions and carry out a major cultural campaign to restore the Amazigh identity to the country."

In the sixties and seventies, students who spoke Tamazight were punished even if they were outside the walls of the school, and in the eighties a woman was investigated because she spoke to her mother on a public phone in Tamazight... The Amazighs of Tunisia demand recognition and support for their culture

The demands of the Amazighs from the state are many and varied. Among them is "the recognition of the Amazigh identity, which includes the language and its teaching in educational curricula similar to other foreign languages, and the state's interest in it so that it does not disappear," according to a member of the "Tamagit" Association for Amazigh Rights, Freedoms and Culture, Muhammad Khalafallah.

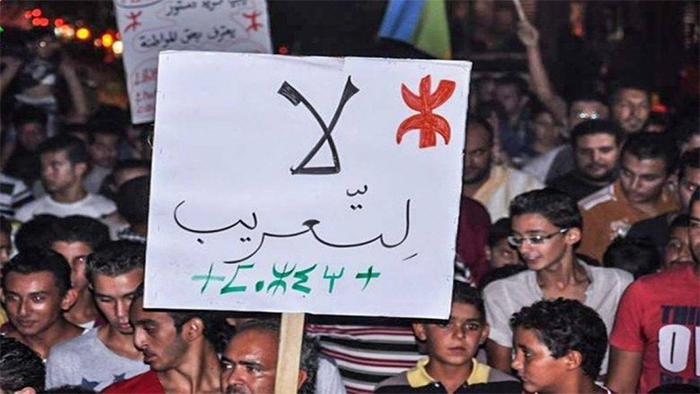

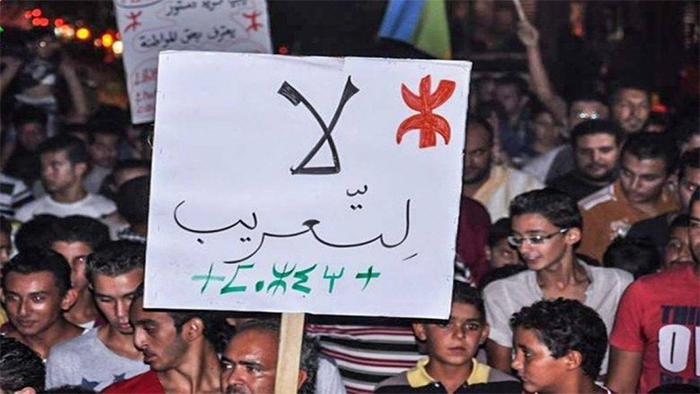

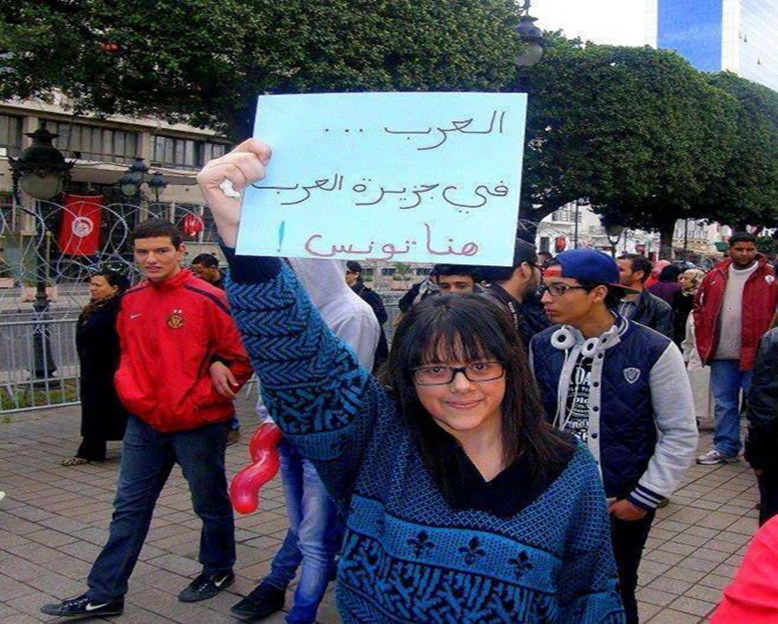

Previously, demonstrations were organized in front of Parliament to demand the inclusion of the Tamazight language and culture in the Tunisian constitution, without anyone paying attention to these demands.

Among the demands of the Amazighs is also "the support and encouragement of 12 existing and recognized associations concerned with Amazigh culture, similar to the support and assistance of other development and cultural associations," as the general secretary of the Tunisian Association for Amazigh Culture, Kilani Boushahwa, calls for. “We are suffering from a lack of resources, and we have not received even a single dinar from state support, and we do not have headquarters to organize activities,” Bushohwa explains. In his opinion, "Tunisian politicians completely reject the Amazigh demands for political and electoral purposes. They are afraid to delve into this issue because if any politician announces his support for the Amazigh movement, his opponents will take advantage of this point to overthrow him by accusing him of trying to divide Tunisia and calling for sedition, given that awareness of this The issue is still not sufficiently widespread in Tunisian society, and there is an important segment that believes in the Arab-Islamic identity.

In this context, he points out that the Amazighs did not receive congratulations from any Tunisian official on the occasion of the Amazigh New Year, while they received greetings from foreign officials.

'sensitive issue'

The Amazigh issue in Tunisia is considered sensitive, and talking about it was taboo before the revolution. There are no official statistics on the number of Tunisian Amazighs who speak the Amazigh language, as Muhammad Khalafallah explains to. However, their number is estimated at about 200,000, mainly concentrated in southern Tunisia.

Al-Shibani points out that all Tunisians are originally Amazighs, but there are speakers of the Tamazight language with its different dialects and are present in the island of Djerba and the governorates of Tataouine, Medenine and Gafsa, and there are Amazighs who are partially Arabised. Although a genetic study conducted by the “National Geographic” magazine concluded that most Tunisians have Amazigh origins, Khalafallah stresses that “the identity of the Amazighs is the land and not the race. ".

Al-Shaibani points out that the Amazigh culture has a specificity that makes them different from the Arabs or the Levantines. It is characterized by a triple motto: Awal (language), Akal (the land) and Afkan (the human being), and its values are based on respect for human freedom. He explains that in the Amazigh language there is no guardianship over the woman, so that the children in the past were attributed to their mothers, and the Amazigh man is the one who covers his face, but the woman does not. He continues that the Amazigh language respects the human being, as it is very rare for it to include swearing and cursing. Likewise, there is no presence in the Amazigh values of the “eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” law, as the offender is isolated and is not punished for the same crime, even if he is a murderer.

Amazigh and Islam

According to al-Shaibani, the Amazighs understood Islam differently from the Islam of the East with its Sunni and Shiite sects. There are no sheikhs to consult because Amazigh Islam draws from the Ibadhi school of thought, which relies on the verse {The most honorable of you in the sight of God is the most pious of you}.

Al-Shaibani points out that "the Amazigh believes in a direct belief without philosophy, and every person works for himself without the interference of the other in his affairs, and he is free in his actions towards God, and whether he fasts or prays or not is considered a criterion for judging him, and the concept of faith for the Berbers is doing good to others." .

Currently, most of the Amazighs are not Ibadis, but they took from this doctrine several things such as refusing to inherit power on the grounds that it derives from the rule of the group and therefore there is no tyranny among the Ibadis and Amazighs. The relationship between the Amazighs and the Ibadhis is ancient, as explained, Tunisian university professor and historian Amira Aliyah Al-Saghir. Because of the persecution and injustice they were subjected to during the Umayyad dynasty, they found what they needed in the Ibadism, which called for confronting the oppression and injustice of the rulers. There is still an Ibadhi community in Tunisia, on the island of Djerba.

Al-Saghir explains that the Amazighs embraced the Sunni-Maliki Islamic school of thought with the Bani Hilal in the eleventh century, and a small percentage of them, not exceeding 5%, fled to the mountainous regions in southern Tunisia and kept their Ibadites. In addition to the followers of these two sects, some of the Amazighs follow Sufi orders such as the Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya, but always within the Sunni sect, according to al-Shaibani.

Tunisian Amazigh culture

Some of the Tunisian Amazighs preserved their language by practicing it and continuing to use it in the villages of Ketmerzit, Zaraoua, Tajut and Qalala. They also preserved the traditional dress and tattoos of women and the Amazigh architecture based on carvings and the use of stone, according to the vice-president of the World Amazigh Congress, Jaloul Ghaki.

"Even after Tunisia's independence in 1956, and despite the forced displacement of the residents of these villages, the villages of Tamzrt and Taoujout still preserved their mountainous locations," Ghaqi confirms.

On his intention to use the expression "forced displacement", he explains that the state "deliberately" deprived these areas of all the necessities for a decent life in order to "displace the indigenous Amazigh population, provided that the displacement is indirect in order to distance itself from accusations." Although there are few Amazigh speakers today in Tunisia, the influences of the Amazigh culture can be seen on all Tunisians simply, as Amazigh dress is common among them, such as the malhafa and the millia (women's clothing), the burnos and the kashabiya (men's clothing). ) and Garana (frog). Therefore, "there is no point in denying the Amazigh identity of Tunisians," according to Mohamed Khalafallah.

opposition to the authorities

Tension characterizes the relationship between the Amazighs of Tunisia and the state. Muhammad Khalafallah states that the Amazigh regions of the south have been known since ancient times for their opposition to state policy during the period of former presidents Habib Bourguiba and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, which resulted in their marginalization and deprivation of the necessary necessities of life such as high schools, electricity and drinking water, and thus forced its people to migrate to cities, and this, in his opinion, was A systematic policy to eliminate the Amazigh culture.

Khalafallah says, "In the sixties and seventies of the last century, students who spoke Tamazight were punished even if they were outside the walls of the school, and it was forbidden to teach young children the Tamazight language in schools teaching the Qur'an."

He points out that the state’s plan aimed to create new areas in the plains bearing the same names as the mountain villages, with the addition of the word “new” to them, and enjoying all the necessities of a decent life, forcing the residents of the mountain villages to abandon their homes and move to live in them or in the capital, thus mixing Arab population and their Amazigh culture is fading little by little.

Tunisian Amazigh youth want to protect their culture in the new constitution

According to the speaker, in 1965 a decision was issued banning naming newborns by non-Arab names, and during Ben Ali’s rule, a woman who was maligned by someone was interrogated because she spoke to her mother on a public telephone in the Tamazight language, and the security forces imposed on her in writing not to adopt this language in public places. Although the UN Human Rights Committee questioned Tunisia in 2009 about the Amazigh issue, the state continued to deny the existence of a problem completely.

"We are the indigenous people"

According to Khalafallah, the matter reached the point of distorting the image of the Tunisian Amazighs by accusing them of demanding secession, explaining: “What happened is that the independence countries in Algeria and Morocco, where the largest percentage of Amazighs are located, imposed in the sixties the Arab-Islamic identity, which means denying the existence of the Amazighs, and clashes occurred. between the Amazighs of the two countries and their authorities, so they linked these movements to the Amazighs of Tunisia and accused us of trying to secede.

Khalafallah denounces the failed state's attempts and tells: "We are the original inhabitants of the region, whether in Tunisia or in the rest of North Africa. We resisted the invaders and colonizers. We clung to our land and fought to defend it. So why do we demand secession? We do not want to divide Tunisia. All we ask for is addition."

He believes that talking about recognizing the Amazigh identity of Tunisia does not mean that they are with the exclusion of any other cultural affiliation similar to the Arab affiliation.

Although Amazigh speakers are few today in Tunisia, the influences of Amazigh culture can be seen on all Tunisians, as Amazigh dress is common among them, and in cooking they eat couscous and broccoli, and they use Amazigh words in their daily conversations.

In turn, the general secretary of the Tunisian Association for Amazigh Culture, Kilani Boushahwa, states that the Tunisian state does not attach the slightest importance to the issue of the Tunisian Amazighs and to the legitimate demands of Amazigh activists and associations regarding the Amazigh language as an essential and original component of the Tunisian personality. He tells Raseef22: "Tunisian Amazigh culture has been obscured and falsified for years, and the matter worsened after independence in 1956, when the regimes Arabized everything, just as talking about Amazighs in the country before the revolution was considered an accusation."

As for Ahmed Mahrouq, he strongly criticizes the "terrible absence of the Amazighs of Tunisia since independence until today," and says: "The history that is taught to children mentions all the successive civilizations in Tunisia and ignores its original Amazigh identity. I grew up and grew up in the Tamazight language that I used to speak in our house with other people." My family, but when I went out on the street, I used to speak the Tunisian dialect, because Tamazight is forbidden.”

He adds: "They don't mention the 'Falaqa' Amazigh resistance fighters who contributed to Tunisia's independence. What we know is that Bourguiba was the only one who liberated Tunisia. They didn't teach us to be proud of our identity. They politicized everything."

Regarding these Amazigh resistance fighters, Ghaqi says: "All the Amazigh-speaking villages included a number of valiant resistance fighters who were independent of any partisan or political action. They were armed in the mountains and resisted the colonialists without belonging to the authority, and they were motivated to do so by their attachment to their land."

freedom but...

After the revolution, there was a breakthrough, albeit a small one, with regard to dealing with the issue of the Tunisian Amazighs. Kilani Bushhawa records that the revolution gave the Amazighs the opportunity to discuss their cause and freedom of organization and activity within the framework of associations that defend their identity. However, he considers that the problem lies in the fact that the state does not want to fulfill the recommendations issued by the meeting of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva in April 2016, which stipulates that culture should be supported. Tamazight and supporting the teaching of the Amazigh language and associations interested in it.

In turn, Muhammad Khalafallah points out that some points changed after the revolution, as the direct restrictions were lifted, and the Amazighs enjoyed freedom of expression and the formation of associations concerned with their cause. However, he considers that the individual efforts of civil society after the revolution, such as offering some voluntary lessons in teaching the Amazigh language, are not sufficient to preserve Tunisia's Amazigh identity. He criticizes the state's view of the Amazigh issue "as a folkloric thing that plays the role of decoration in some cultural events." He says, "We are an integrated and deep culture that is not limited to the image of women milling grain."

Source : websites