?Why is “La Catrina” associated with the Day of the Dead in Mexico

On April 13, 1944, police tried to contain a crowd of several thousand people on the steps of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The gathering had nothing to do with U.S. involvement in World War II, labor unrest, or President Franklin D. Roosevelt's controversial decision to take control of Chicago's local industries.

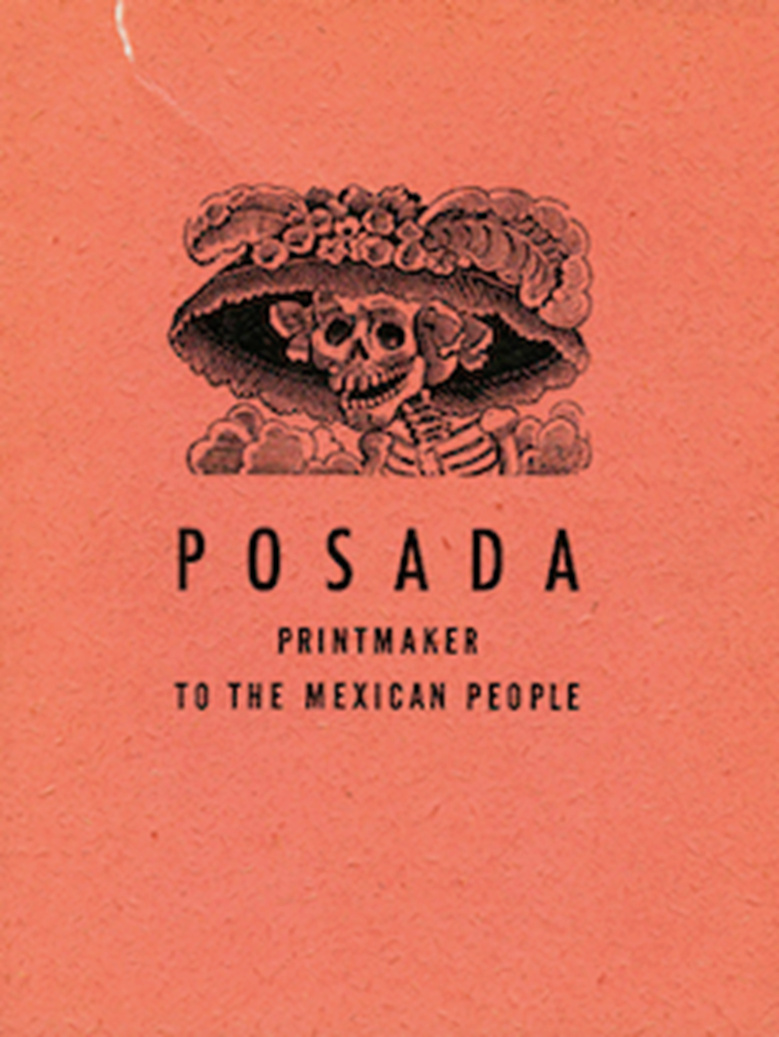

In reality, they were visitors eager to visit the museum. Because everyone wanted to enjoy the American premiere of an exhibition entitled “Posada: Printmaker to the Mexican People”.

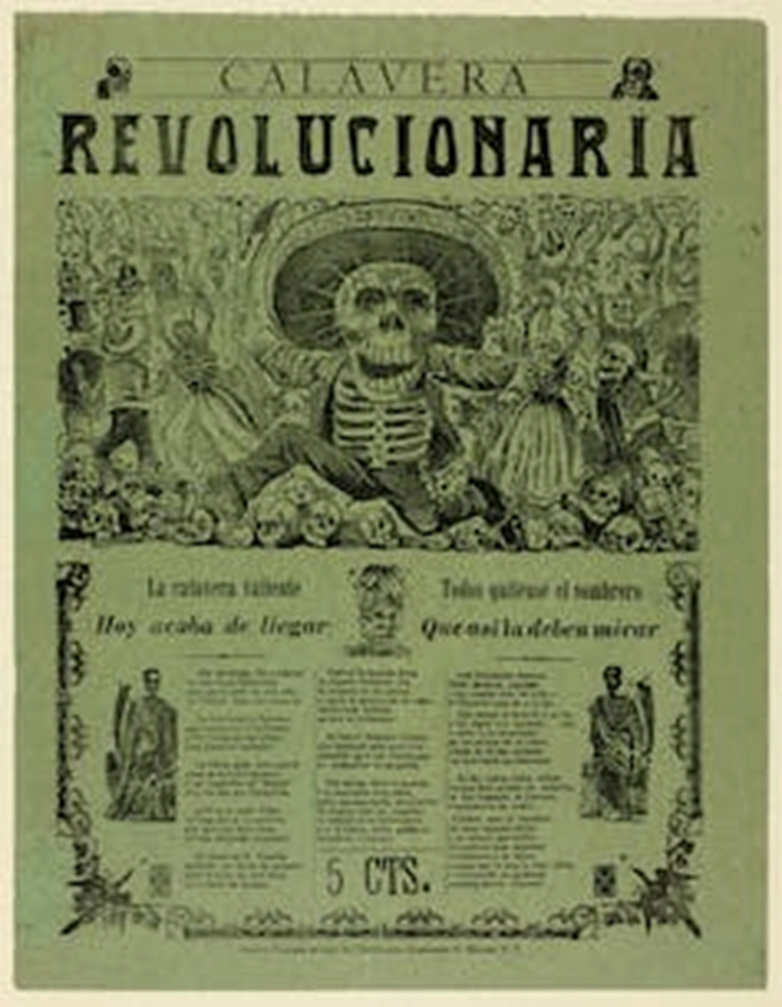

The exhibition featured the prints of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican printmaker who died in 1913. The exhibition featured his calaveras (skulls), satirical illustrations of skulls and skeletons made on the occasion of All Souls' Day and printed on cheap newspapers printed on a loose sheet, the “broadsides”.

One of these calaveras attracted more attention than the others.

Known as La Catrina, she was a garish skeleton sporting a wide smile and an oversized feathered hat. A large reproduction of her hung on the wall of the museum. The public had seen it in the museum’s promotional materials. She even appeared on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. In Mexico she was virtually unknown, but American exposure made her an international sensation.

Today, La Catrina is Posada's most recognizable creation. She is the icon of the Day of the Dead, the annual Mexican holiday in honor of the deceased which takes place each year on November 1 and 2. Her face is reproduced endlessly during the festival, so much so that she has become the unofficial national totem of Mexico, after the Virgin of Guadalupe.

While some may think it has always been this way, La Catrina is in reality a transcultural icon whose prestige and popularity are the result of both invention and accident.

A dark life

When Posada first engraved it in 1912, it wasn't even called La Catrina.

In the original print, she is Calavera Garbancera, a title used to refer to indigenous peasant women who sold garbanzo beans (chickpeas) in street markets.

Posada outfitted her in flashy clothing to satirize the way garbanceras attempted to pass themselves off as members of the upper class by powdering their faces and wearing fashionable French clothing. Thus, from the beginning, La Catrina was transcultural – a rural indigenous woman adopting European customs to survive in Mexico's urban, mixed-race society.

The catalog cover of “Posada,” a 1944 exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, features the woman who would become known as “La Catrina.” zoomable= The Art Institute of Chicago

Like Posada's other illustrations, the 1912 poster was sold for a penny to primarily poor and working-class men in and around Mexico City. But the Calavera Garbancera was nothing special. Like its creator, it remained in the shadows for many years.

Posada died broke and unknown, but his illustrations survived him. His publisher reused them for other posters until the 1920s. La Calavera Garbancera was recycled into various other characters, none particularly noteworthy. And no one really knew who made the calavera posters that we saw in the capital every All Souls Day.

Things changed in the mid-1920s, when Posada's work attracted the attention of French artist Jean Charlot, a leading figure in the Mexican Renaissance, that creative explosion of nationalist murals and artwork that occurred in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution.

‘Revolutionary Calavera,’ by José Guadalupe Posada, printed on a broadside.” zoomable= Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Charlot was fascinated by the calavera illustrations he saw in Mexico City, but he did not know who created them. He eventually tracked down Posada's publisher and began researching the engraver. Charlot published articles about Posada and introduced the artist's calaveras to other artists and intellectuals of the Mexican Renaissance. Among the most important are the painter Diego Rivera and the critic Frances Toor.

From La Garbancera to La Catrina

Rivera, of course, is arguably the greatest artist in Mexican history. His epic murals remain famous around the world.

Frances Toor, on the other hand, was a modest Jewish intellectual who made a career writing about Mexican culture. In 1925, she began publishing Mexican Folkways, a popular bilingual magazine distributed in Mexico and the United States. With Diego Rivera as art editor, she began using the magazine to promote Posada. In the October-November annual issues, Toor and Rivera presented large reprints of Posada's calaveras.

However, the Garbancera calavera is never one of them. It was not important enough to be presented.

In 1930, Toor and Rivera published the first book of Posada's prints, which sold throughout Mexico and the United States. But it has a new name: Calavera Catrina. For unknown reasons, Toor and Rivera chose this honorific adjective, which makes them a kind of feminine dandy. The calavera is forever La Catrina.

but it was with the Posada exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1944 that she truly became famous. The exhibition is the result of a collaboration between the museum and the Mexican government. It is funded and facilitated by a special White House propaganda agency that used cultural diplomacy to build solidarity with Latin America during World War II.

This promotion allowed the Posada exhibition to tour and give La Catrina greater visibility. It has been seen and promoted in New York, Philadelphia, Mexico City and elsewhere in Mexico.

The exhibition catalogue, with Catrina on the cover, was sold at each stop of the tour. Free copies were also distributed to prominent American and Mexican authors and artists. They began writing about La Catrina and reshaping her in their artwork, popularizing her on both sides of the border.

La Catrina goes international

In 1947, Diego Rivera further immortalized La Catrina by putting her at the center of one of his most famous murals, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.

This mural depicts the history of Mexico, from the Spanish Conquest to the Mexican Revolution. La Catrina sits at the center of this story, with Rivera painting her holding Posada's hand on one side and a child's version of himself on the other.

Detail of Diego Rivera's mural "Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park", which is in the Diego Rivera Mural Museum in Mexico City. Nick Sherman/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Rivera’s celebrity – and La Catrina’s newfound solemnity – inspired Mexican and Mexican-American artists to incorporate her into their works.

Folk artists in Mexico began making them into ceramic toys, papier-mâché figurines, and other crafts sold on All Souls Day. Mexican Americans used La Catrina in their murals, paintings, and political posters as part of the Chicano Movement, which aimed to advocate for the civil rights of Mexican Americans in the 1960s and 1970s.

La Catrina's image is now used to sell anything from beer to Barbie dolls. You can order La Catrina costumes at Walmart and Spirit Halloween stores.

In fact, La Catrina parades and costume contests are a relatively new Day of the Dead tradition in Mexico and the United States.

Every year, Los Angeles native Christina Sanchez dresses as 'Catrina Christina' for Day of the Dead. Mars Sandoval, CC BY-SA

Some people, like “Catrina Christina” in Los Angeles, don a costume every year to honor their loved ones on Día de los Muertos. Others dress up as Catrina to increase their number of followers on social media, or pretend to be her to make money.

Posada probably didn't expect his calavera to become so famous. He simply wanted to use traditional humor to make fun of the flamboyantly dressed garbanceras he saw hanging around Mexico City's central square.

Today, during Día de los Muertos, this same central square is filled with hundreds of La Catrina impersonators who, for a few dollars, pose for photos with tourists who are more than willing to pay for such a cultural experience." traditional” with an “authentic” Day of the Dead icon.

Posada, meanwhile, is probably laughing somewhere in the land of the dead.

Source: websites