"THE GHIBUNTEN SECTS"...DANCING ON THE HERITAGE OF SLAVERY

A few days ago, I finished reading the notes of a trip undertaken by Henry Dunant (founder of the Red Cross) to Tunisia for a year between 1858 and 1859. In those memoirs, Dunant establishes - with a high human touch - a broad comparison between the conditions of blacks in Tunisia and their counterparts - at that period - in the United States of America. His praise of Field Marshal Ahmed Bey was wide, and his vilification against the American elites was broader. The praise of the Bey, the enlightened reformer and modernist ruler, came after the decision to free the slaves in 1846, which preceded all the Arab countries and the Ottoman state, a decision that Tunisia also preceded the United States of America by more than 18 years.

Meanwhile, during which Dunant was wandering in the city of Tunis, groups of slaves in the far south were getting their freedom thanks to the decision of Field Marshal Ahmed Bey. Its geographical area is in the Kasbah area of the delegation of “Sidi Makhlouf” in the present-day Medenine Governorate, in the southeast of the country.

Everything is distinctive about this tribal group: its historical roots, its narrative formation, its lifestyle, the quality of its arts, the way it dresses, the contents of its texts, the scenes of its performances and performances. It is also a vivid and vivid witness to a large chapter of the modernization process in Tunisia, which began in the mid-nineteenth century.

In the south of Tunisia, with the beginning of each summer, the wedding season begins, and it seems like an old custom (in the entire Maghreb space) that is basically linked to the end of the harvest seasons. There is also an old proverb, in the region, that says: “The glory is upon the glaciers, and the wedding is upon the swarms . ” This ancient and ancient proverb in the Tunisian southeastern heritage, which seems difficult to understand, due to its complex specificity, summarizes - in fact - a complete cultural, social, and even historical painting.

The decision to liberate the slaves in the year 1846 by Field Marshal Ahmed Pasha Bey , the enlightened reformer and modernist ruler, preceded all the Arab countries and the Ottoman Empire, as Tunisia preceded it also the United States of America by more than 18 years .. In his book “ The Sociology of the Tribe in the Maghreb ”, Professor Mohamed Najib Boutaleb deconstructs what he called the “indicator of the division of labor” between tribes in the Maghreb. Tribal social work.” With the fighting tribes, the peasant tribes, the religious tribes, and even the commercial tribes, he points out that there are “other groups that perform functions no less important than the previous ones, such as those that perform ceremonial functions among the Negroes, such as the Obaid Ghibinten tribe in southern Tunisia, which practices singing and music” (Boutaleb). , p. 113).

The Jalidat are a religious Almoravid tribe, and the descendants of a famous Wali Saleh in the region, so they are the ones who perform the “Hadra” ritual as a religious and therapeutic ritual. Whereas, it is the “sects” of the “Obeid Ghibinten” tribe that perform “ceremonial functions” by reviving wedding parties. This parable summarizes part of the painting “The Tribal Division of Social Labor” in southeastern Tunisia.

The wedding, here, in the southeast of Tunisia, extends over three full days. Usually the second night is the night of the big party. And that night is often furnished, especially by a performance of “The Sects of Obaid Ghibinten.” This wedding, which Ghabnten attends, is described as “a wedding by tyrants” or “a slaves’ wedding.”

But what are these sects? And why are they called “Obeid Ghabntin”?

“Ghabten” are a black-skinned “ethnic” group that is distinguished by exceptional privacy, through its lyrical performances at celebrations and weddings in southern Tunisia. social and political. Therefore, they are not only lyrical texts or mere performances of watching, but rather a complete oral collection of texts/documents that bear witness to history, society and its transformations.

To summarize the issue in its historical and sociological meaning, we have to say that Ghibinten is a tribe that belongs to a union and despite the tribalism that inhabits the southeast of Tunisia, and Ghibinten is divided into two branches : the original “ white ” branch, and the “ black ” branch, which merged with it since the mid-nineteenth century, After the Emancipation Act, he took her name and also shared her geographical area . This second branch, “ black ” in complexion, which is called “ Obeid Ghibinten , ” is the one who exercises these “ ceremonial functions ” within a painting . The tribal division of social work ” in the south of Tunisia .

Dr. Mohamed Jouili, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Tunis, studied this ethnic group extensively and in depth in a book entitled “ Communities of Memory, Societies of Forgetting : A Monographic Study of a Black Minority in Southern Tunisia .”

TRIBE, SECT, AND “NEGRO MUSIC”

Regardless of the discussion that the topic may provoke about the concepts of ethnicity and tribe, and where Professor Naguib Boutaleb points out in his introduction to the aforementioned book Muhammad Al-Juwaili that “the “Obeid Ghibinten” model is distinguished by the presence of the ethnic and tribal dimensions at the same time”, when we talk about the word “Taifa Ghibinten” is within this conceptual and idiomatic overlap. We are specifically talking about one of the artistic groups belonging to that tribe. The Taifa (Taifa as it is pronounced in the local dialect) is simply an artistic group of “Obeid Ghibinten”, which performs at marriage ceremonies.

In fact, there are a number of sects that belong to this ethnic group, and these sects are not found anywhere else in the world nor are they even found in the same original “white” branch of the tribe. The sect, then, is the artistic troupe that descends exclusively from the “black” tribe of Ghibintan, and it has its own structure, the quality of its performances, its strict internal organization, and its artistic and performing rituals of presentation, dress, and rhythm.

In his aforementioned book, published in 1994, the researcher Muhammad Al-Juwaili records five sects divided into three family branches within the tribe (Communities of Memory, p. 116), while a study conducted by the National Institute for Heritage (governmental) in the year 2021 identifies seven sects in Ghibtan. These sects, which decrease and increase according to time, eventually form part of the mosaic of “Negro music” in Tunisia.

“Negro” music is intensely and powerfully present in Tunisian culture, and takes on a religious dimension mostly, through its reliance on a righteous guardian, within the ancient religious and Sufi culture in society, and it is also, especially - Negro music – combines in being part of the long heritage of slavery. country, and one of its most important remains and sediments. Al-Stambali is one of the most famous manifestations of this music, with its unique artistic, cultural and historical peculiarity. However, unlike Stambali and the rest of the components of the “negro” music scene in Tunisia, the Ghibinten sects “do not pay much attention to religious ceremonies in the context of their cultural practice,” as researcher Mohamed Ahmed points out.

This meaning is also confirmed by Muhammad al-Juwaili by saying that Ghibin “does not hold religious ceremonies and does not care about the therapeutic dimension in their cultural practice. They only celebrate wedding ceremonies, so the Al-Satanbali teams have a sacred aura that none of the “Obeid Ghabentan” teams can obtain” (Communities of Memory, p. 114).

In the south of Tunisia, in contrast to the Ghibinten sects, we also find the “tabbalah ” teams formed by “negroes” belonging to the various Arab and Berber tribes, who did not unite like the Ghibinten into one tribe, but rather merged or merged as individuals and families with different tribes, and these teams also furnish weddings and celebrations It is very different from what the Ghibin sects offer through other musical contents and instruments.

It seems that this competition between the two parties, over the “market” of weddings and celebrations in the region, is what prompted one of the Ghibin sects to denounce the “tabbalah” performances in one of its songs , when she says, “Oh, Nagai Sbeik, I am blown away by the wedding of the drums.” The dancing of women and men // Something that turns shame.” This sentence from the local dialect means: “Why did you become a fan, O our local community, of the weddings of drummers? This does not suit you. In it, women dance with men, and this is shameful.” The intensity of moral slander on the performances of competing drummers is not hidden in the text, but with some exaggeration, in fact, men never dance with women in these performances.

In the performances of the Ghibinten sect, a strict - and almost sacred - division of the ceremonial space is strict. A specific place for the bride and groom to sit, a specific location for the traditional tent that is always at the front of the courtyard, a specific space for women and another for men. Within that finely divided arena, the sect presents its show based on poetry, singing and collective performance.

The word “slaves” in describing the tribe and its sects raises a real problem. It is full of sedimentary and shameful racist meanings, which sometimes go beyond words and descriptions to actual expressions in the lived social reality. It also invokes an ancient history and heritage, transcended by history and modernity. The new generation in Ghabnten never accepts this description. Older generations also reject it as stigmatization. That is why they are also called the “Shawashin” which is the name that “members of this minority are comfortable with and always want to use. Because the social ladder places the disorder in a middle position between the free people who occupy its highest ranks and the slavs or slaves who lie at the bottom of this ladder” (Communities of Memory, p. 72).

But the shawashin is the word that is said in their presence only and “is absent when it is spoken about these people in their absence, and often they are called slaves, so it is said that they are “obed Ghabantan” and “a wedding with slaves” (same page).

In this context, Al-Juwaili refers to a very important observation, when he says that “what is remarkable is that these names (Ubaid, Saffan, Shawashin) are used in all regions of the southeast except for Djerba. The residents of Djerba call this minority “the Talibs” (p. 73).

This name is due to the economic charge, which means that the members of this group are requesting funds to hold weddings, according to Al-Juwaili, which was based - according to his analysis - on economic considerations and not other considerations related to color and origin and does not contain any derogatory or exclusionary shipment, due to that the island of Djerba “a refuge for many religious and ethnic minorities in particular. It is a stable for the Jewish minority and some sectarian (Ibadhi) and ethnic minorities such as Berbers. Its inhabitants, then, have a degree of dealing with these minorities, which is a social and economic deal in particular. Which makes them less severe in their epithets and names for the minorities present on the island or outside” (Communities of Memory, p. 73).

On the other hand, despite this, the Ghibinton sects succeeded in exploiting their status as a “black minority” within their social environment, and succeeded in exploiting a narrative that they formed as a tribe of freed “slaves,” turning all of that “stigma” into a real exception and distinction. Through a clear social and historical genius, the Ghibtan sects turned this dominant social and cultural heritage into a source for the development of the economic capital of the tribe, which mainly engaged in agriculture and sea fishing outside wedding seasons in the summer.

It has also succeeded, through its arts and festive performances, in imposing itself within this environment, opening up to it, and entering its parties and social events. When the Ghibintan sect dances at a wedding party, it is in fact dancing on an entire heritage of the history of slavery, and it places an important position for itself on the social and economic map, within the “tribal division of social labor” panel, to find itself thus no different from any other social or tribal component, Sometimes it even managed to take premium positions.

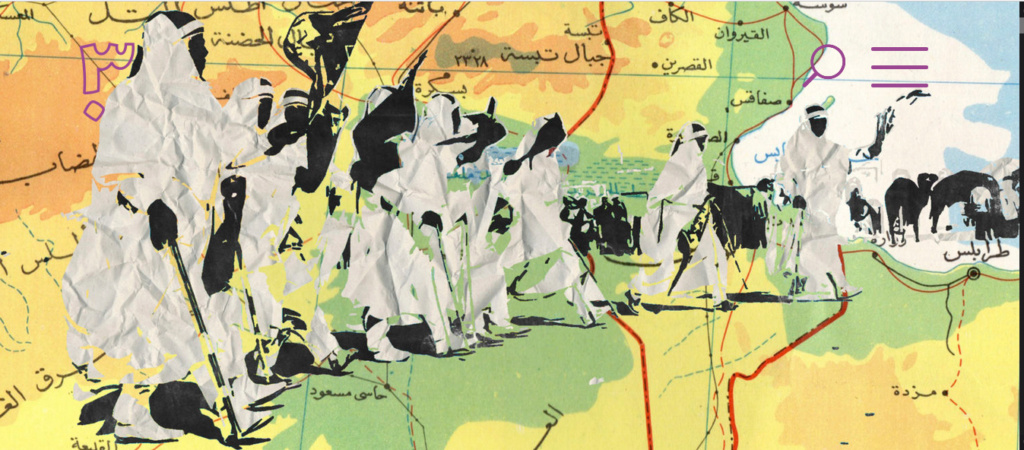

The genius of Ghibentin lies not only in its success in social integration, transcending its historical status as a minority of freed slaves, and investing that across sects/sects to turn it into an advantage, not a stigma, and a source - as well - of economic wealth. This genius also lies in the aesthetic creativity of image, movement, melody and word. This is evident in the quality of her art that she created and the way she performs. And also in its iconic distinction in terms of dress and colours. The sect only wears a special dress that is made with precision and skill inherited among the women of the tribe. White costumes from the elements of the traditional dress of the south of Tunisia, and red handkerchiefs around the neck and in the hand to be used in the dance scene.

In the performances of the Ghibinten sect there is also a strict - and almost sacred - division of the ceremonial space. A specific place for the bride to sit and another for the groom, a specific location for the traditional tent (the ishah as it is called in the local dialect) which is always at the front of the courtyard, and a designated space for women and another for men. Within this finely divided arena, the sect presents its poetry-based performance, singing and collective performance of poems accompanied by the percussion of the "shanna" (a drum made of camel skin), the only instrument used in the show.

The most important thing that distinguishes the Ghibinten sects, especially and more than anything else, is their lyrical and poetic texts, which are distinguished by their richness, pictorial eloquence, the strength of their words, and the complexities of their symbols, especially by their historical and documentary function, and their social and human implications.

However, the most important characteristic of the Ghibinten sects, especially and above all, is their lyrical and poetic texts, which are distinguished by their richness, pictorial eloquence, the strength of their words, and the complexities of their symbols, especially their historical and documentary function, and their social and human implications. Therefore, the leader of the sect, who is the one who composes its poems, and is called the “Rais”, must be an articulate poet, capable of attracting listeners and achieving success for his sect and marketing it for the quality of its texts and the strength of its themes.

With the sect’s leader, poet and responsible, and the owner of the largest share of the sect’s income as well, there is the “Bahriya” which consists of the rest of the troupe’s members who chant the poems sung with the sect, including one who specializes in percussion and another one who specializes in collecting money, which is provided by the sect. The ramification process. Which means the sums that the listeners pay at the wedding party to the band / sect to request a poem, or when admiring one of the poems, and then the person charged with “rammo” takes the money to announce its owner loudly, mentioning his name and lineage, and praising his generosity, under the ululations of women, and those sums that The band / sect collects it throughout the evening - which is often important - it is the main income of the sect, which does not take money from the owner of the wedding. Therefore, Ghibenten excels in the poem and the word, and they are keen on that because it is a source of revolution.

In the “removal” process, some remnants of sedimentary, and also hidden, slavery are evident. When the person charged with collecting money takes the sum from one of those present, he turns to his party to mention loudly, that everyone (especially women) can hear the name of the motive and its lineage that precedes it, saying , “ to the members of your sect .” and addressing them.

In his aforementioned book, Muhammad al-Juwaili notes the presence of the marine metaphor in the appellations “Al Rayes” (meaning in the Tunisian dialect the captain of the ship) and “Al Bahariya” (members of the band / sect) likely to be due to the “African origins of this group, especially if it comes from the coasts.” ». (Communities of Memory, p. 115). In fact, this presence of the “marine metaphor” can be understood in a less complex way, since the Ghibinten was originally a marine tribe living in a village on the coast and fishing as a major source of income.

As for the name “sect” according to al-Juwaili, “it is a name associated with minorities and is not alien to them, and it indicates the distinction of a group of elements within this minority in their ability to poetry and sing” (same source). Indeed, excellence in poetry and word is what makes a sect’s superiority and success, and ensures its radiance and fame, and thus the multiplication of its financial resources.

LIVE ARCHIVE

Despite the simplicity of rhythm in the performances of the Ghibinten sects, which rely only on the “shanna”, a drum made of camel skin, its distinction lies in the strength and content of its sung poems. Ghabnten's poems - despite the difficulty of their words and their deep local dialect - transcend the traditional frameworks of ceremonial poems, to make them documents chronicling historical facts and political events and texts that deal with social phenomena.

Despite the presence of the political dimension in the poems of the Ghabntin sects, no anti-authoritarian stances are known about them in Tunisia, especially before the revolution, where “these poems are controlled by the official political position. They try “when composing their poems, to follow the official line of the state in attitudes and directions, because failure to adhere to this line means confiscating their activity and cutting off a major source of their livelihood” (Al-Juwaili, p. 135). However, the poets of Ghibinten, on the other hand, were always a patriotic trumpet at the time of the struggle against colonialism, by vilifying its practices, praising national leaders, documenting the events of the resistance and narrating the lives of the resistance. In addition to the fact that many of them were active participants in the national struggle in the first half of the twentieth century.

Al-Fituri Tillich is considered one of the most famous historical poets of Ghibinten. The man who lived through the colonial period has always been an echo of the national struggle movement, denouncing colonialism and siding with the national leaders, praising them and documenting the historical events that took place in that period. His poems caused him to be imprisoned by the French occupation, which prompted him to intensify the use of symbolism in his texts. The late researcher Mohamed Marzouki (one of the most important documentaries of popular poetry in Tunisia) published a collection of Al-Fituri Tillish's poems in a diwan published in the mid-seventies that includes various purposes and the most famous patriotic and social poems that he created.

Fitouri Tillich sang about former President Habib Bourguiba and documented in a highly symbolic poem the event of his exile to the deserts of southern Tunisia in 1934 by the French. Al-Fitouri Tillish also sings songs about the struggle against colonialism, led by Mohamed Daghbaji , one of the most famous symbols of the armed struggle in Tunisia.

Politics and national events are heavily present in Ghabnten's poems. This poem by the sect “Mabrouk Baltoumi” chronicles the event of independence and the expulsion of France, as its beginning says: “God has given us victory and we have taken it out, and now it is in our hands” (God gave us victory over France and expelled it from Tunisia, which today is ours and in our hands). In the poem we also hear the glorification of Bourguiba, who proclaimed the Republic, describing him as “Babana” (Father).

With their deeply local dialect and figurative aftermath, Gbenten's texts are living documents of social, economic and political transformations. Documented events and related phenomena. With a value content that raises the meanings of solidarity, peace, patriotism, unity and rejection of extremism

The political interest of the Ghibinten sects does not stop at the local and national affairs, but extends beyond it to interest in all other Arab issues. In one of the texts of these sects, we find documentation of the events of the “Libyan revolution” in 2011. In 2014, with the outbreak of the second civil war in neighboring Libya between the forces of General Khalifa Haftar and the forces of Fayez al-Sarraj, we find one of the sects of Ghabantan documenting in precise detail these events .

The Palestinian issue is also heavily present in Ghabnten's texts. And other local issues, such as the case of the Kamour protests in southern Tunisia, which we find documented in one of Ghabnten's poems . The poems of the Ghibinten sects do not neglect any important local event that they document in his poems, as we observe in a poem about the bloody tribal confrontations that took place in southern Tunisia months ago between the “Al-Hawaya” and “Al-Maraziq” tribes.

Corona also did not pass, as a global event and a phenomenon worthy of treatment, without being present in the poems of the Ghibtan sects. These poems/texts also deal with all the phenomena that interact in society, and their convergence from different angles, such as the issue of immigration, especially illegal immigration or “harqa” as it is called in the local dialect.

In one of her most famous poems , the Ghabentan sects document the incidents of the “Bengardan epic” when ISIS tried to take control of the border city, but the security forces and the people confronted it, and the terrorist attack was thwarted.

With their deeply local dialect and figurative aftermath, Gbenten's texts are living documents of social, economic and political transformations. Documented events and related phenomena. With a value content that raises the meanings of solidarity, peace, patriotism, unity and rejection of extremism. This is what gives these poems, and these sects, and Ghabantan in general, their distinction and makes their uniqueness, local spread and success. Waiting for these sects to achieve Arab and international spread that could shed light on a distinct cultural component in Arab culture and even humanity. This is what a new documentary film by director Samah Majri is trying to confirm , entitled "Tawaf".

In his latest lyrical work, directed by the Italian Francesco Garbo, Tunisian artist and music researcher Islam Jamaï revive one of the poems “Ghabten” composed by one of the most famous poets, the late Ali Tilish. “We hide in a stranger” is a social poem that talks about poverty and privation, the need in a harsh society, and the helplessness in front of life’s requirements and difficulties. Al-Jami’s selection of one of the sect’s songs, redistribution and directing it into a video clip , and projecting its content on today’s reality, with an international production, seems like a useful step as well and an important push towards removing these sects and their heritage from the narrow locality to the Arab and international spread, which may contribute a lot to the efforts of successful inclusion . Within the UNESCO human heritage as sought by the State Heritage Institute in Tunisia.

Despite these official efforts to protect and preserve the heritage of these sects, this heritage faces other problems, some of which are internal, related first to the need to adapt the dialect in a way that helps to understand the contents of the sung texts on a broader level ( national and Arab ) , and secondly, to the problem of transmitting this heritage to new generations. Thus, ensuring the continuity of this artistic heritage . Some of these problems are also external, including the encroachment of artistic groups and the decline in the consumption of these sects in wedding ceremonies, which themselves have begun to lose their old system and reduce many of their ceremonial paragraphs and rituals .

https://khatt30.com/post/%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d8%a8%d9%88%d8%af%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%ba%d8%a8%d9%86%d8%aa%d9%86/?fbclid=IwAR0xxF5cxH-s3TVk2P1a49Vcg00WwIuWeyiI81oQlWC1ZCRFRWaYezcI72o