Ashurbanipal

King Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE, also known as Assurbanipal) was the last of the great kings of Assyria. His name means "the god Ashur is creator of an heir" and he was the son of King Esarhaddon of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. In the Hebrew Tanakh (the Christian Old Testament) he is called As(e)nappar or Osnapper (Ezra 4:10), while the Greeks knew him as Sardanapolos and the Romans as Sardanapulus.

He achieved the greatest territorial expansion of the Assyrian Empire which included Babylonia, Persia, Syria, and Egypt (although Egypt was lost as a result of a revolt under the reign of the Egyptian Pharaoh Psamtik I). Ashurbanipal was a popular king who ruled his citizens fairly but was marked for his cruelty toward those whom he defeated, the best-known example being a relief depicting the defeated king with a dog chain through his jaw, being forced to live in a kennel after capture.

He is best known for his vast library at Nineveh, which he himself considered his greatest achievement. Under Ashurbanipal's reign, the country of Elam (which had long been an unconquerable enemy of Assyria) was destroyed and Urartu, another long-time adversary, was dominated. Toward the end of his reign, however, the empire had grown too large and too difficult to properly defend. The Assyrian Empire was already crumbling toward the end of his reign and, with his death, fell apart completely.

Early Reign & Egyptian Campaigns

Esarhaddon had conquered Egypt in 671 BCE but the Egyptians had revolted soon after and driven many of the Assyrian governors from their posts. In 669 BCE Esarhaddon mobilized his troops and marched back to put down the revolt but died before he reached the Egyptian border. Prior to leaving on campaign, however, he had fortunately decided to set his affairs in order. When his father, Sennacherib, had been assassinated, Esarhaddon had been forced to fight a six-week war with his brother's factions to secure the crown. He did not want to see this same thing happen with his own heir.

IN BETWEEN COLLECTING HIS LIBRARY, RENOVATING NINEVEH, & RUNNING THE EMPIRE, ASHURBANIPAL CONTINUED TO LEAD HIS OWN MILITARY CAMPAIGNS.

Esarhaddon's eldest son and heir, Sin-iddina-apla, had died in 672 BCE and Esarhaddon now chose his second son, Ashurbanipal, as his successor. He forced his vassal states to swear loyalty in advance to Ashurbanipal in order to avoid any revolts over the future succession. At about this same time, Esarhaddon's mother Zakutu issued the Loyalty Treaty of Naqia-Zakutu which compelled the Assyrian court and those territories under Assyrian rule, to accept and support the reign of Ashurbanipal. In order to avoid the kind of conflict he had gone through with his brothers, Esarhaddon also provided for his youngest son, Shamash-shum-ukin, by decreeing he should be king of Babylon.

Ashurbanipal succeeded Esarhaddon in 668 BCE and ordered a great coronation festival for his brother's ascension to the throne of Babylon. In his inscriptions, he writes how Shamash-shum-ukin was welcomed to Babylon “amidst rejoicing” as the statue of the great god Marduk (taken from Babylon in 689 BCE by Sennacherib, who sacked the city) was returned to the people. He elevated Babylon to its former status as a great city and refers to Shamash-shum-ukin as “my favorite brother”. Once he saw that Babylon and the southern territories of his empire were secure, he led his armies south toward Egypt to finish what his father had begun.

King Ashurbanipal (Artist's Impression)

Esarhaddon had conquered the Pharaoh Tirhakah but had not killed him. Tirhakah's family had been brought back as captives to Nineveh and remained there but he and his extended family had fled south to Nubia. When Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt c. 667 BCE he drove his army south as far as Thebes, sacking every rebel city in his path. The only ruler spared was the king who had remained loyal to Assyria, King Necho of the city of Sais. Necho's son, Psamtik, had been brought back to Nineveh by Esarhaddon for re-education in Assyrian ways and beliefs and now was returned to his father to rule with him. Ashurbanipal divided the territories of Egypt between these two kings and then, in the belief that Egypt was secure, returned to Assyria to deal with problems with Elam. Tirhakah's nephew in Nubia, however, a young man named Tatanami, recognized Egypt's vulnerability under the new rule of the joint kings and decided to seize the opportunity.

Tatanami marched on Egypt and took each city on his route with minimal effort. At the capital of Memphis he engaged with the Egyptian-Assyrian forces under the command of King Necho. Although Psamtik was able to successfully repel the Nubian army, Necho was killed in the battle. The Egyptians preferred the rule of the Nubians over that of the Assyrians, however, and Psamtik was driven into hiding. In 666 BCE, word of the rebellion had reached Nineveh and Ashurbanipal returned at the head of his troops and again crushed the rebels.

Lion-hunting Scene, King Ashurbanipal

Their stronghold at Thebes was sacked and Tatanami abandoned his campaign and fled back to Nubia. Ashurbanipal then made Psammetichus full Pharaoh of Egypt, equipped him with Assyrian garrisons stationed at strategic points, and then again returned to Assyria in 665 BCE. Between 665 and 657 BCE he put down a rebellion in Tyre, fought the Elamites, led his army through Anatolia to reconquer the people of Tabal, and subdued the kingdom of Urartu which had again risen to threaten Assyrian interests. While he was engaged in these campaigns, Egypt was slowly slipping from his grasp.

The First Elam Campaign & Babylon's Revolt

Psamtik was not content to rule as an Assyrian puppet and so began to assert his independence by making deals with various Egyptian governors and courting the favor of Gyges, the king of Lydia in Anatolia. In 653 BCE, with the help of the Lydians, Psamtik drove the Assyrian troops out of Egypt and established his new capital at the city of Sais. Although news of this revolt was brought to Ashurbanipal's attention, there is no record that he returned to Egypt to do anything about it. Elam, Assyria's old enemy, was causing problems closer to home and Ashurbanipal considered that a priority.

By the year 653 BCE, Shamash-shum-ukin had also grown tired of being Ashurbanipal's puppet king. Inscriptions from Babylon indicate that Ashurbanipal had been dictating his brother's decrees and managing his affairs. Other inscriptions indicate that Shamash-shum-ukin sent secret enjoys to the king of Elam asking for support in throwing off the Assyrian yoke. Ashurbanipal, it seems, knew nothing of his brother's schemes and was only aware that the armies of Elam were mobilizing for an assault on Babylon and, taking the offensive, he marched his army to Elam and attacked.

Assyrian Soldiers Engaging with Nubian Soldiers at Memphis

He defeated the Elamites and sacked their cities. According to his inscription, he killed the Elamite king Teumann and his son with his own sword: “With the encouragement of Assur, I killed them; I cut off their heads in front of each other.” He then brought the heads back to Nineveh where he hung them in his garden as decoration. Since Ashurbanipal did not know his brother had invited the Elamites to Babylon, Shamash-shum-ukin continued with his rule and Ashurbanipal continued to dictate it.

Even if he had known his brother was complicit in the Elamite invasion, he would have had no time to deal with the problem. A coalition of Medes, Persians, and Cimmerians marched on Nineveh in the same year and brought their forces within reach of the walls. Ashurbanipal called upon his Scythian allies, known for their skill as cavalry, and defeated the coalition, killing the king of the Medes, Phraortes.

Shamash-shum-ukin was no more pleased than he had been before at being his brother's puppet, however, and in 652 BCE openly rebelled. He took Assyrian villages and outposts and claimed them in the name of Babylon. When Ashurbanipal responded by marching his army to the region, Shamash-shum-ukin retreated behind the walls of Babylon where he was besieged by the Assyrian forces for the next four years.

Inscriptions from the time relate what the defenders of Babylon endured behind the walls: “They ate the flesh of their sons and daughters because of starvation.” When the city fell, those who had survived so long were cut down by the Assyrian soldiers and, Ashurbanipal writes, “The rest of those living I destroyed…and their carved-up bodies I fed to dogs, to pigs, to wolves, to eagles, to birds of the heavens, to fishes of the deep.” Shamash-shum-ukin set himself on fire in his palace in order to escape capture. Ashurbanipal then set an Assyrian government official named Kandalu on the throne of Babylon.

The 2nd Elam Campaign

At the same time Babylon fell in 648/647 BCE, Elam erupted in civil war. The king of Elam had died and now different factions fought for the throne. Ashurbanipal saw an opportunity to finally defeat his old enemy and drove his army again into Elam. The historian Susan Wise Bauer writes, “Elamite cities burned. The temples and palaces of Susa were robbed. For no better reason than vengeance, Ashurbanipal ordered the royal tombs opened and the bones of the kings bundled off into captivity” (414). When he sacked and destroyed the city of Susa in 647 BCE, he left behind a tablet which recorded his triumph over the Elamites:

Susa, the great holy city, abode of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed... I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt.

Anyone with even the slightest claim to the throne was captured and brought back to Nineveh as a slave. In keeping with Assyrian policy, Ashurbanipal then relocated enormous numbers of the population throughout the region and left the cities empty and the fields barren. Bauer writes:

Ashurbanipal did not rebuild after the wrecking of the country. He installed no governors, he resettled none of the devastated cities, he made no attempt to make this new province of Assyria anything more than a wasteland. Elam lay open and undefended. (414)

This would later prove to have been a mistake as the Persians slowly took over the territory which had once been Elam and proceeded to re-build and fortify the cities. In time, they would help topple the Assyrian Empire.

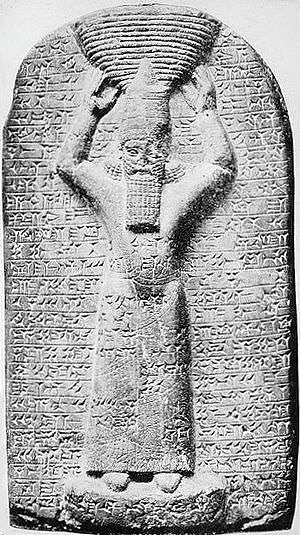

Ashurbanipal as High Priest

Ashurbanipal's Library

Following the destruction of Elam, however, the very idea that the empire would not last forever would have been considered absurd. There was no rival or near-rival to the might of the Assyrian Empire at that time. The Assyrian's ancient enemies of Urartu and Elam were both defeated and, even though Egypt had broken free, it had still been stamped with Assyrian culture. The other territories of the empire which had rebelled had been dealt with severely and brought back in line.

Ashurbanipal was a great patron of the arts and now turned his attention to these pursuits. He established his famous library of over 30,000 clay tablets at Nineveh. Among the works found in the Library of Ashurbanipal were the Enuma Elish (the Babylonian Epic of Creation) and the great epic tale of Gilgamesh, the oldest adventure story extant. It was among the tablets of Nineveh that the original Mesopotamian story of the Great Flood, which pre-dates the story in the Bible, was found in the 19th century CE and the library's discovery has since been considered one of the greatest and most important archaeological finds in history.

Cylinder of Ashurbanipal II

Ashurbanipal claimed to be able to read cuneiform script in both Akkadian and Sumerian and his collection of writings was vast. According to the historian Paul Kriwaczek, "Ashurbanipal went further than mere ability to read and claimed complete mastery of all the scribal arts" (250). In his own words, Ashurbanipal claimed:

I, Ashurbanipal, within the palace, understood the wisdom of Nabu [the god of learning]. All the art of writing of every kind. I made myself the master of them all. I read the cunning tablets of Sumer and the dark Akkadian language which is difficult to rightly use; I took my pleasure in reading stones inscribed before the flood. The best of the scribal art, such works as none of the kings who went before me had ever learnt, remedies from the top of the head to the toenails, non-canonical selections, clever teachings, whatever pertains to the medical mastery of [the gods] Ninurta and Gala, I wrote on tablets, checked and collated, and deposited within my palace for perusing and reading.

Kriwaczek further notes that this is no idle boast of the king as there is actual proof that Ashurbanipal could compose in cuneiform and cites tablets which are signed by the author as "Ashurbanipal, King of Assyria". In collecting his famous library he wrote to cities and centers of learning all across Mesopotamia instructing them to send him copies of every written work ever set down in the entire region. Kriwaczek writes:

He was concerned not just to amass as large a collection as possible, but to ensure that he had copies of every important work in the Mesopotamian canon. In the letter [to the governor of Borsippa] he goes on to list prayers, incantations, and other texts, identified, as was usual in ancient times, by their first words. (251)

The immense size and scope of his library at Nineveh is testimony to how successful he was in collecting the works he requested from his subjects. Bauer comments:

As far as Ashurbanipal was concerned, his library was the abiding accomplishment of his reign: “I, Ashurbanipal, king of the universe, on whom the gods have bestowed intelligence, who has acquired penetrating acumen for the most recondite details of scholarly erudition (none of my predecessors having any comprehension of such matters), I have placed these tablets for the future in the library at Nineveh for my life and for the well-being of my soul, to sustain the foundations of my royal name.” Esarhaddon might have managed to keep Egypt, but Ashurbanipal's realm of the mind would last forever. (410-411)

Death & the Fall of the Empire

In between collecting his library, renovating Nineveh, and running the empire, Ashurbanipal continued to lead his own military campaigns. He also oversaw renovations at Babylon. By 629 BCE, he was in ill health and left Nineveh for the city of Harran to the north. He left the empire in the hands of his son Ashur-etel-ilani but this decision was challenged by the new king's twin brother, Sin-shar-ishkun and a civil war erupted.

The territories of the Assyrian Empire took advantage of this division and began to exercise more autonomy than they had been allowed previously. When Ashurbanipal died in 627 BCE the empire broke apart. As Bauer writes, “Disorder swallowed almost every part of the empire” as former vassal states declared their independence (416). Between 627 and 612 BCE, the empire steadily dissolved as Medes, Persians, Babylonians, Cimmerians, Scythians, and Chaldeans burned and sacked the Assyrian cities.

In 612 BCE, Ashur, Kalhu, and Nineveh were destroyed in the great conflagrations which swept the land. Ashurbanipal's library was buried beneath the burning walls of his palace and was lost to history for over 2,000 years. Their discovery, however, changed the way people in the modern day understood culture and the past.

Prior to the discovery of Ashurbanipal's library, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world and the stories it contained were thought to have no precedent. Excavations in the 19th century CE by Sir Austen Henry Layard, Hormuzd Rassam, and translations made by George Smith brought to light a world which no one up until that time was aware of. Ashurbanipal's empire fell and the territories he conquered went on to be conquered by others and then by still others, but his library endured and, as he claimed himself, turned out to be his greatest accomplishment.

Bibliography

Bauer, S. W. The History of the Ancient World. W. W. Norton & Company, 2007.

Bertman, S. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Durant, W. Our Oriental Heritage. Simon & Schuster, 1954.

Kriwaczek, P. Babylon. Thomas Dunne Books, 2014.

Leick, G. Mesopotamia. Penguin, 2002.

Leick, G. The A to Z of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press, 2010.

The Chronology of the Reign of Ashurbanipal by A.K. GraysonAccessed 1 Dec 2016.

Timeline of Ashurbanipal's ReignAccessed 1 Dec 2016.

Van De Mieroop, M. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 - 323 BC edition. Wiley-Blackwell, 2019.

Von Soden, W. The Ancient Orient. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994.

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

About the Author

Joshua J. Mark

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

https://www.worldhistory.org/Ashurbanipal/